Of Better Africans, Racisms and Pan Africanisms: A Review of Retorts to Panashe Chigumadzi’s “Why I am no Longer Talking to Nigerians About Race’”.

It was Fredrich Hayek who said, in his ‘Constitution of Liberty’ – that if old truths are to retain their hold on men’s mind, they must be restated in the language and concepts of successive generations. Panashe Chigumadzi’s essay on her disillusion with how Nigerians discuss race generated a lot of debate, and offers a chance to restate old truths – in a digital age of fleeting patience and overwhelming data. Amidst the noise came some clear retorts, which help to get a rounder figure of the true discussions of racial politics in Nigeria, among Africans, and in the Diaspora.

Four Nigerians responded to her essay, with each addressing issues they consider the essay`s blind spots. However, all of them, in turn, betrayed their position like the six men of Hindustan. In putting these five essays in conversation with each other, I am hoping that a better picture of racial politics in Africa can be formed. As a Nigerian-born, South African-educated, and American-trained, I hope to offer a synthetic reading of the conversation.

First – a rehash of Chigumadzi. Her arrival at Ake literary festival, on a panel that sought to dismiss the importance of #BlackLivesMatter, and her appreciation of the confidence of schoolgirls arrayed in their colourful coiffeurs in Uganda, made her consider that Nigerians lack the experiential range to appreciate Black racial politics in settler colonies and in the Diaspora. She saw the light after climbing the fortresses of Olumo rock, which were mere pebbles as compared to her house of stones in Zimbabwe (The word Zimbabwe is house of stones in Shona). After all, did Wole Soyinka (the Nigerian Nobel laureate in whose hometown the literary festival was being held) not dismiss Negritude as irrelevant? She explains Soyinka’s complacency with a contrast of Eski’a Mphahlele’s childhood in Down Second Avenue. While little Wole grew up safe in the sanctuary of Ake, largely untainted by the colonial gaze as he describes in his childhood memoir Ake, little Eski’a had no such luxury growing up in Apartheid South Africa.

This raises a central fundamental question of politics. Can you understand, if you have not walked in someone’s shoes? What are the limits of these forms of empathy?

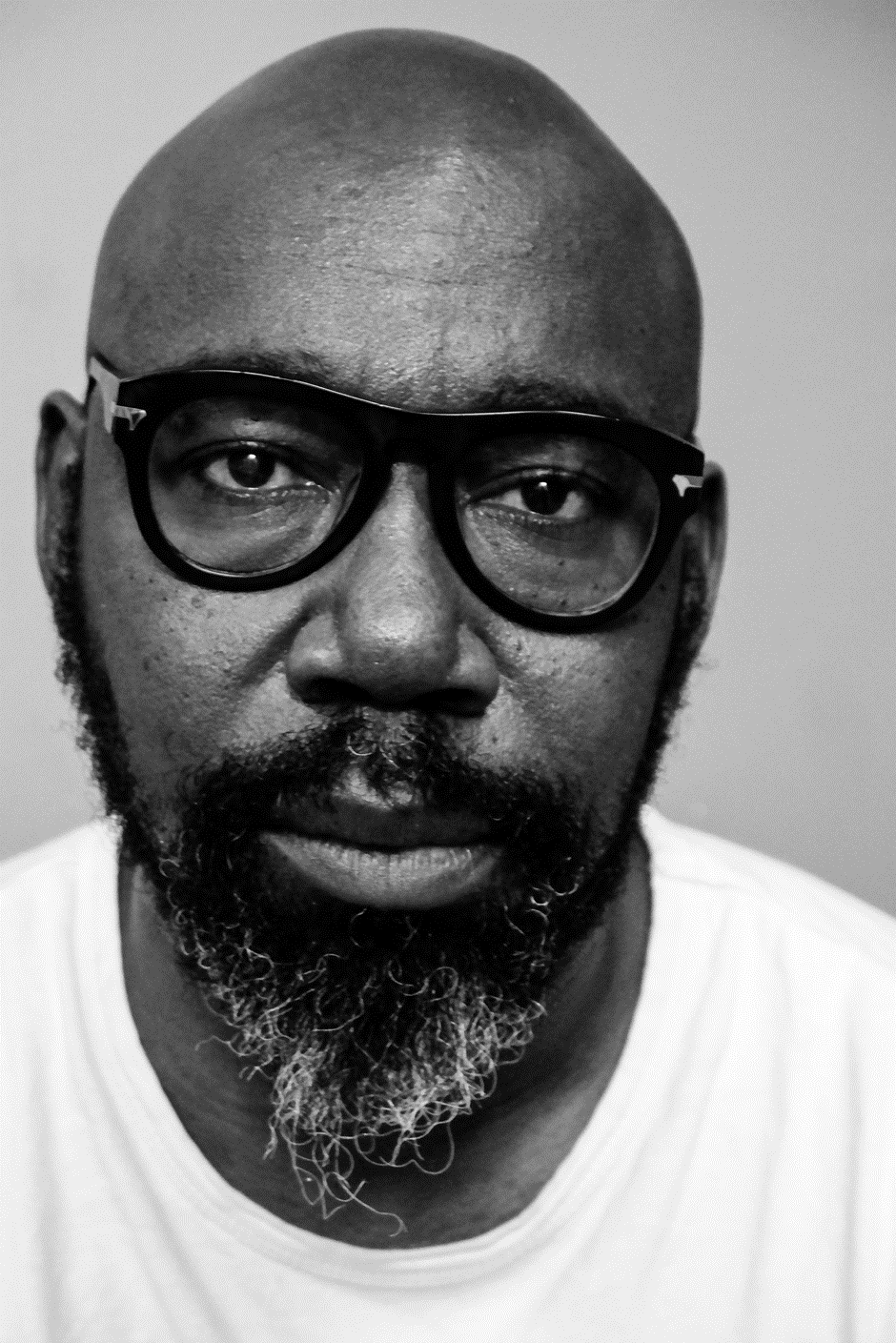

Nigerian-American literary critic, Ikihide Ikheloa, applauds the conversation starter – Chigumadzi’s piece. A perpetual thorn in Nigeria`s political and intellectual class, Ikhide’s take is instructive, as the model African who migrates to America for the golden fleece, and settles down in America when the country he left behind to return to offers little solace. It is no wonder that he does not take any prisoners, when he takes on the Nigerian establishment. As he says, context matters when we discuss Nigeria’s lack of solidarity for global racial anxieties. He sees the annual purchasing power of African Americans as a sign of progress to be envious of, by other Africans. Well, there is one, for context.

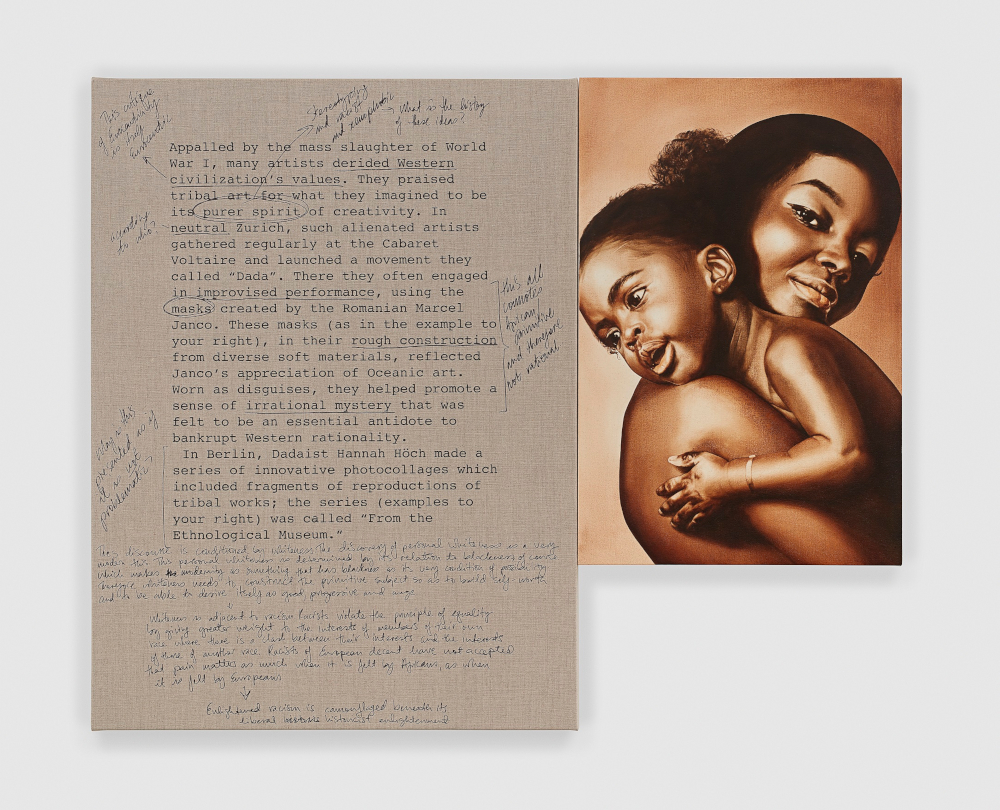

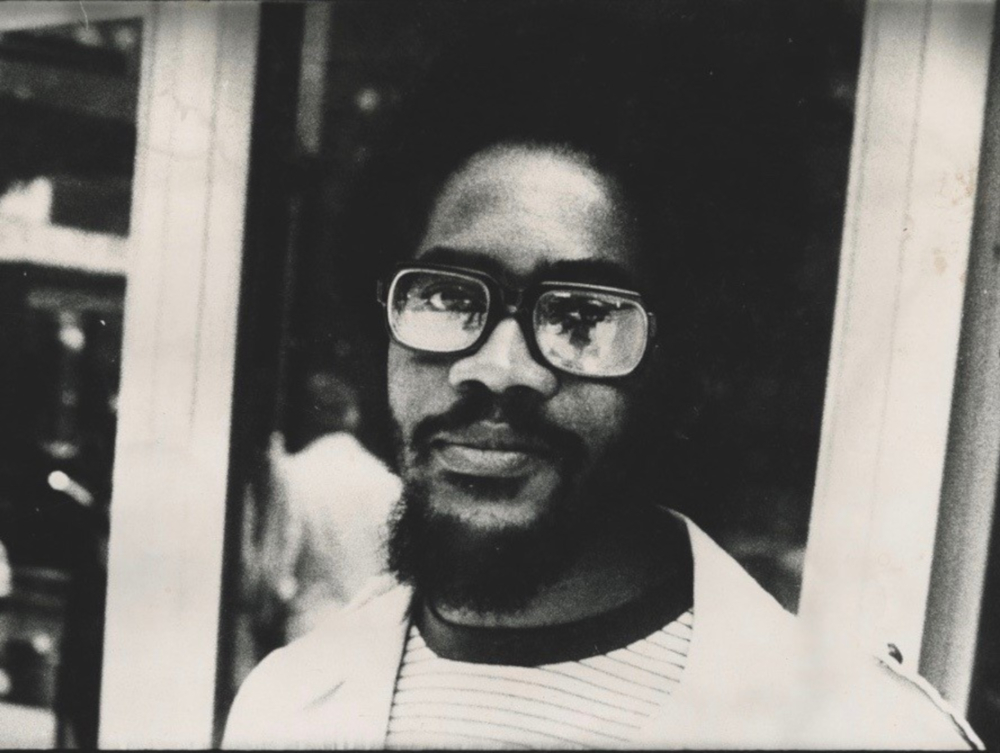

Akin Adesokan censures the lack of curiosity, turgid criticism and encourages the eschewal of easy answers, among African creatives born in the digital age. His intervention seeks to fill the gap in Chigumadzi’s assertion that Soyinka’s loud derision of the Negritude movement was symptomatic of Nigerians’ apathy to matters of Pan-Africana. Drawing on personal engagement with the critic James Gibbs, and a closer reading of events, Adesokan corrects the mistake that Soyinka was being flippantly dismissive of the Negritude Movement. In fact, he was being true to the taste of his age at that time. His assertion that, “The duiker does not paint ‘duiker’ on his beautiful back to proclaim his duikeritude. [Y]ou’ll know him by his elegant leap,” was in response to the older generation of Pan-Africanists, like Leopold Sedhar Senghor and Aime Cesaire, whose claims for Negritude foregrounded the poetic qualities Blackness as an affirmation of difference. It was this position that Soyinka rejected. For him, it was not enough to shout “I am black and proud” – an anthem of a nostalgic ideation of Blackness rooted in America, which resonated across the Atlantic and found reverberations in the affirmations of Negritude.

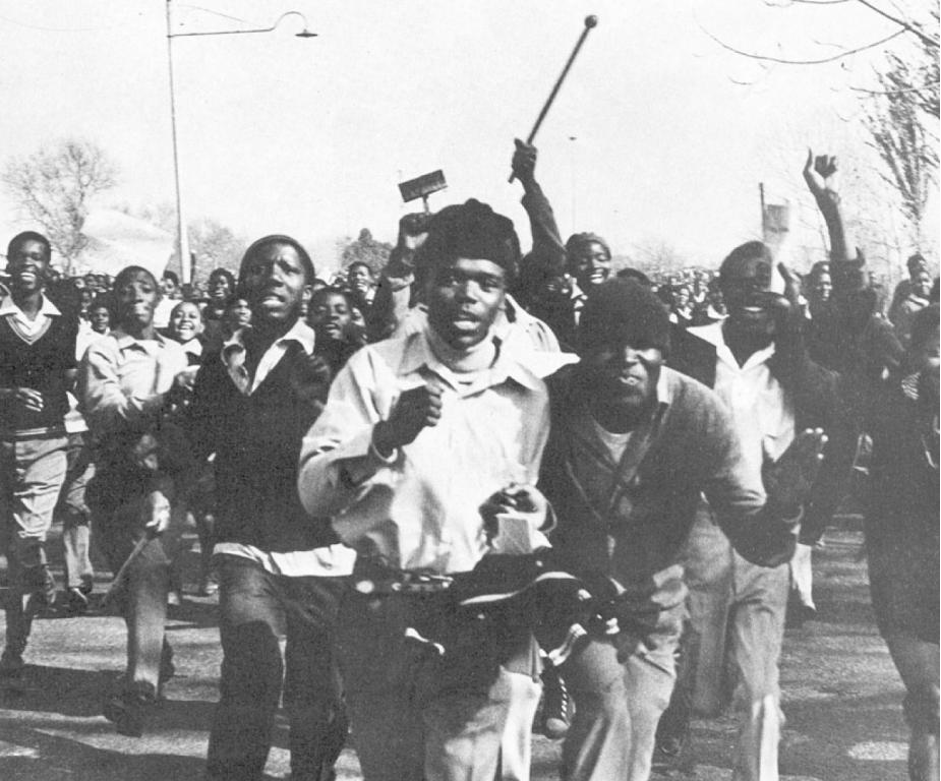

To claim Soyinka, as the archetype of Nigeria’s indolent Pan-Africanism, was mistaken. More so, it is to not recognise the contributions of ordinary Nigerians in bottom-up Pan-Africanism. The charge of a Nigerian apathy to racial matters around the world is strange, and can only be posited by a millennial whose reading of the world is majorly formed through books. As a child born in the 80s in Lagos, it was hard to miss the commentaries on the Apartheid government – from Sony Okosun’s ‘Fire in Soweto’ release in 1978, to Queen Salawa Abeni’s congratulatory message on Nelson Mandela`s release in 1990, and in between that Fela Kuti’s ‘Beasts of No Nation’ – which indicted the United Nations, Thatcher, and Reagan in their complicity with the P.W. Botha-led Apartheid system. Every spectrum of Nigerian society was politicised in matters Pan-African. Kollington Ayinla sang a song closest to being the lullaby of my childhood: Mandela, Mandela, O lo fara ji ya ni to ri ominira…

It is not surprising then that it was a citizen, Mrs. Maude Obanye, who wrote to the soldier-diplomat – Joseph Garba, the then External Affairs minister – after a radio broadcast marking Africa Day, detailing the crimes in Pretoria. This would kick-start the idea of a voluntary tax, called the Mandela Tax or known officially as the Southern Africa Relief Fund, which would go on to raise the most monies by any government against the apartheid government.

To try to remove class analyses is to miss the point about the different degrees and ways in which racialism and coloniality work across classes and countries.

Saeed Hussein’s rejoinder to Chigumadzi’s piece tries to explain Nigeria’s indictment from a lack of class analysis in racial matters, using the 2019 elections. He tried to do too many things at once, and did only one sufficiently – showing that class analysis mattered in explaining the 2019 elections, and the absence of it in our discussion of race hides the complexities. I agree with Saeed Hussein, but not for the same reasons to which he alluded. The absence of racial categories in the top echelons of Nigeria’s economy, as compared to that of South Africa, adds nothing to the discourse. With their respective history, one expects no less. What makes this more interesting is to take into account how much the South African economy is dependent on white fragility.

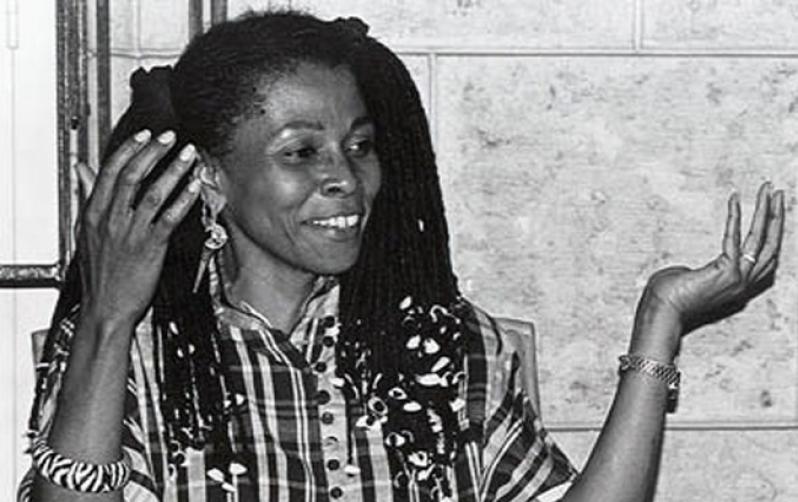

Eniola Soyemi, the only woman to respond to Chigumadzi, picks a bone with her piece – by rejecting the comparison of the bruises of Blackness, as Chigumadzi does in her derision of the rocks of Olumo, compared to her Zimbabwean stone. The distraction of racialism, as is the comparison of whose stones is bigger or more historic, stands in the way of true Black solidarity, Soyemi argues. She who asks, demands a response. Chigumadzi has brought these shows of chest-beating upon herself and the unsuspecting commentariat. That notwithstanding, these conversations need to be had, for all our sakes. It is a good thing it was a Zimbabwean, with a South African upbringing, who provoked it. These exchanges highlight the importance of travel and dialogue.

It is easy to enjoin people to see us, but what happens if we still see others in the lenses that caucasity has bestowed? The Nigerian sees the South African as lazy. The African sees the African American thus. What is the surprise then, when the African-American and the Black South African see another African as dubious – reaping from gains they didn't sow... These may be distractions, but they are not irrelevant. While we are here, we should all remember what Malcolm X says – you can't understand what is going on in (Alabama) if you don't understand what is going on in the Congo. The same interests are at stake. The same sides are drawn up. The same stakes. No difference whatsoever. Or, as they say in academic circles, a mere distinction without a difference.

Twitter: @ajibolaadigun