Freda (2021) is a determined character-perspective film. Written and directed by Gessica Geneus in their narrative feature film debut, Freda often falls into juvenile storytelling, but remains impactful through its singular focus on the titular character, whose acting performance weaves the project together. Certainly, Geneus subverts common masculine portrayals of strength and story, creating a Black feminist perspective on struggle.

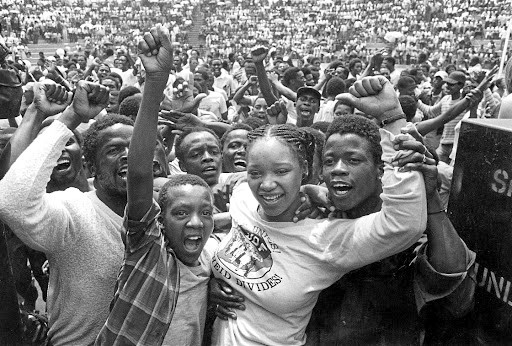

We see how precarious Haitian life has become following the devastating earthquake, the outbreak of violent protests, and the rampant corruption of the state. But, somehow, Freda (Nehemie Bastien) stands tall, carrying her family through this everyday tragedy, maintaining responsibility for her mother and siblings, earning income, and attending university. Freda is exceptionally strong, the film reveals. Despite her world falling apart, her lover threatening to leave her, being admonished by her mother, and being caught in the nightly crossfires of the night, Freda refuses to crumble.

STAY IN STATURE

In some lenses, this is a film about surviving the dangerous social dynamics within suburban Haiti, where the confluence of patriarchy, violence, corruption & disaster rings throughout. Brilliantly, the film starts by explaining the historical struggles faced by each of the supporting characters: shot by a stray bullet, silenced in class, bleaches their skin, romantically rejected by a white local, abused in a marriage-of-convenience, escaped across a border, abandoned by their husband, and on.

Freda’s mother, Jeanette (Fabiola Remy) has collapsed, often unable to speak, wrought by guilt, lashing out, and trying to hold onto a semblance of control she has long lost. What is remarkable about Remy’s performance in the film is how Jeanette transforms from a comedic light character to a shattered sourness. The earlier comic relief creates unsuspecting space for immense horror. The first pain is that we now know that Jeanette’s mother is a hollow shattered character. The second pain is that we once were laughing at her. Toward the end of the film, Freda calls her mother by her first name, creating a sense of equality between the two. We see Jeanette devolve to the level of her child as the film progresses, in what is a phenomenally well-written turn-of-event.

Freda on her mother’s lap

We do not know much about Freda’s own personal struggles, which empowers her characterisation as selfless. By living the film’s conflicts through the supporting cast, the story tells us that Freda’s cause is to help resolve such issues faced by those around her. Where usually a perspective-character is self-oriented, this film is outward. This subverts the expectation for the character to show their strength or competency through their ability, thoughts or perspectives. Instead, we understand that Freda is strong because she refuses to surrender, she cares, she strives. This more feminine display of strength also subverts traditionally masculine portrayals of toughness.

Freda is not tough because she is aggressive and forces her way. She is tough because she (unlike Jeanette) upholds, she stands through, she stays in stature.

CHOICE, CATASTROPHE

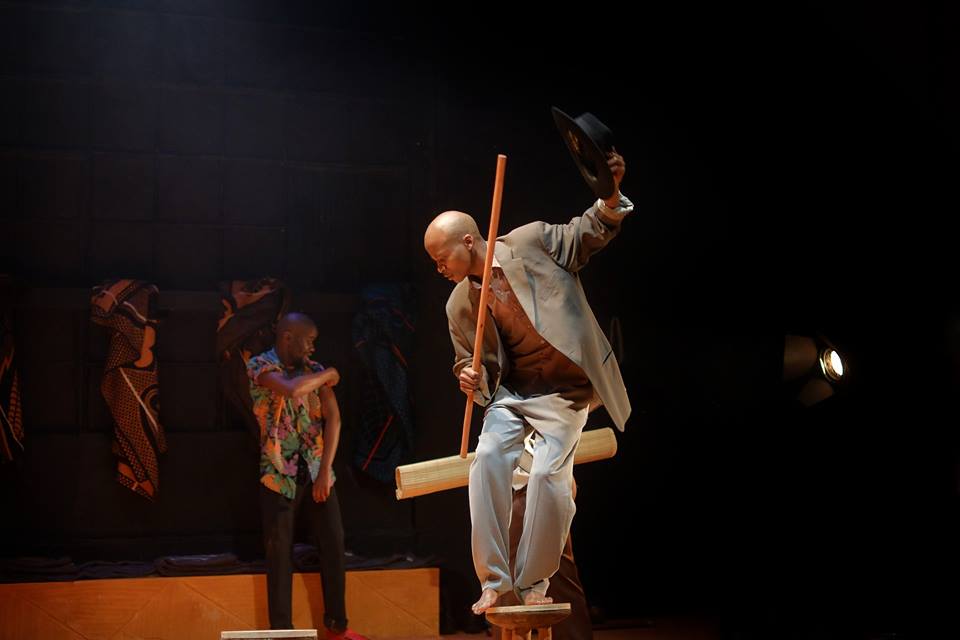

But, Freda is also a young woman who enjoys nightlife, dance and music. She is romanced by art & revelry. She occupies the dual desire to maintain her home and to escape it. The film shows how this contradiction can only be resolved by Freda choosing one or the other. Freda’s lover, Yeshua (Jean Jean), gives her an ultimatum to run away with him or stay without him.

Choice plays a significant role in the film as Freda’s mother is haunted by her decisions. Minor characters often experience direct tragedy after making risky, uncalculated choices. A family friend, Geradline (Gaëlle Bien-Aimé), loses her white lover (and son of her boss), who rejects her after she tells him of her pregnancy. In the next scene, we see Geraldine mourning in her arms. Later, Freda’s sister, Esther (Djanaina Francois), is abused by her husband, a state senator that she hurriedly marries for money. In one scene, before the abuse is revealed, we see Esther’s face of grief when her ex-boyfriend, who she left, takes the stage at a local bar. Geraldine & Esther are remorsed by their choices.

Left to right: Geraldine (Gaëlle Bien-Aimé), Freda (Nehemie Bastien) & Esther (Djanaina Francois).

At the same time, there is not much choice at all. The conditions around the women in the film are extreme social pressures. They rely on men for money. Freda & Esther must look after their brother. Their mother expects as much too, pressuring Freda to leave school (and going so far to find Frieda a job) while pushing Esther to get married. The catastrophe is shown to be inevitable, slowly building from the beginning of the film. It is not so much the character’s choices which are to blame. Yeshua is shot by a stray bullet while he sleeps, innocently. The big reveal explains that Freda was sexually assaulted by her mother’s boyfriend. These events are not the fault of the character’s choices, but show how much of their autonomy is, in fact, robbed of them.

This is then the brilliance of the film. The characters are morose because they realise that they have no valuable choices, and when they think they have made a good choice that finally liberates them, they are brought back into the fray. This could explain Freda’s decision to not go with her lover, knowing the catastrophe that has defined their lives cannot so easily be escaped, it must be survived.

Ultimately, we learn of Freda’s own struggle to make sense of tragedy. Throughout the film, we see Freda through the struggles of other characters. But now, once we learn of her own history, and once all the other characters have, in some way or another, fallen apart — we just see Freda.