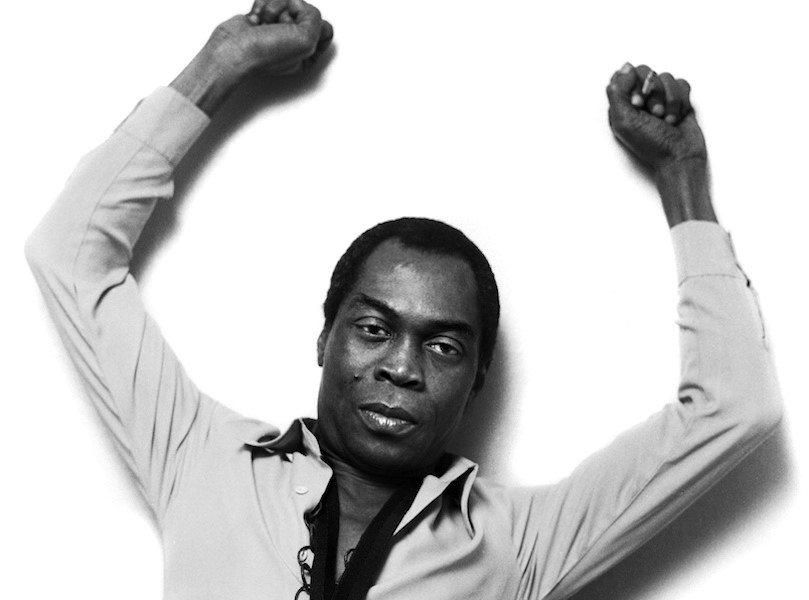

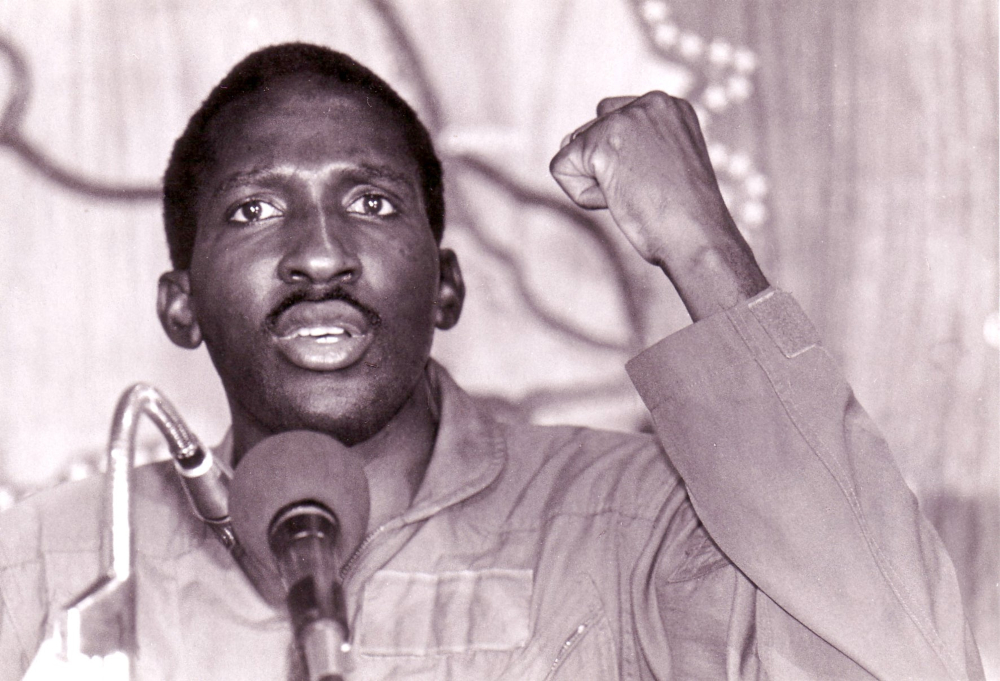

Black of skin and relegated to so-called dusty streets: these are the people for which Makhafula Vilakazi has written and spoken. The inhibitors of townships streets: walking long miles while merciless rains seep into the holes on the shoes barely covering their feet. The hungry: the begging, the Zamalek drinking the cigarette smoking, magwinya le mangola eating, Jesus of Nazareth praying darkies. From omama bo Manyano to abo maqhuzu ngama okapi, these are modern day gentiles and carriers of generations of grief, sorrow and the fleeting sense of what it means to can never belong. In the 27th year of South Africa’s so-called freedom, the Black condition ranges from the perfect suburban life, if your ID number carries the right amount of struggle credentials to living beneath the squalor and suffering of a working-class existence if your ancestry is made up merely of the foot soldiers. These are the characters on the stage of Makhafula’s theatre. While we try to make sense of the killings of Tatane, Mambush and the 34 at Marikana, we’re presented with more martyrs in the forms of Nateniël Julies and Mthokozisi Ntumba and many others. Every day we are reminded that we are the kind of beings who aren’t really human, the kind that is so dispensable that beyond the hashtag and momentary anger our memories mean nothing. Yes, us, descendants of Collins Khosa and the nameless sons and daughters of Langa and Boipatong who never made the headlines, have an archive in the form of spoken words, sorrowful keys and the poetry within Concerning Blacks.

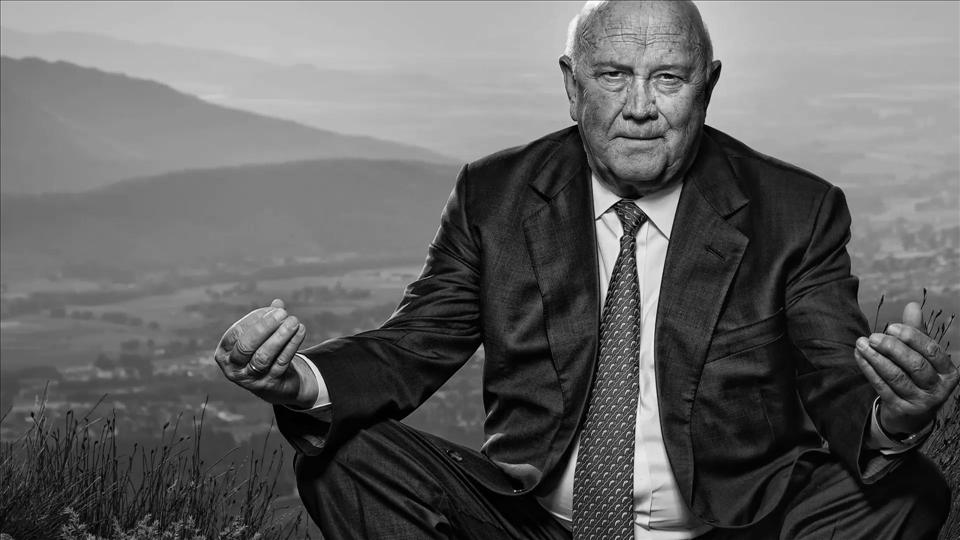

To be Black in occupied Azania: truly is a struggle. A struggle so well encapsulated in the words of Makhafula, concerning blacks. In occupied Azania the fertile soil of Stellenbosch continues to produce gainful harvest while the streets of Khayamnandi stay seeped in musty, dark sewerage water. The victims who forgave the indifferent perpetrators, who now enjoy the fruits of the forbear’s oppressive efforts, have seen that the police who are meant to protect them can just as easily kill them and that economic freedom is a dream never to be attained in our lifetime. We are the whispers within the words of Makhafula: we’re Gift Skoloto, the middle-class black who covers the disgrace of poverty with the diamond incrusted mask of debt, we’re the sleeping M’Afrika depicted in Ulele. The one who drowns his sorrows in the sour sips of ugoloko that offer temporary relief from the perpetual trauma that comes with living in this skin. We are wearers of the blood-stained shoes that paint the precipice of a plunging nation. Covering our ears from the screams of woeful mothers as their faces meet the fists of our enraged fathers. We’re those who are relegated to lifelong survival, like flowers growing between the cracks of ghetto streets we’re the kind that keeps on keeping on.

The word which was used in the deception of our ancestors says something about the beginning and its relation to the word. “In the beginning was the word, the word was God and the word was with God” – it is a different beginning but one that speaks to the start of our own colonially colored sorrow. In the beginning a European spoke words, amongst them he mentioned God and heathen and between his opening prayer and his final benediction we lost our land and all that we had come to know as being of us. The word stole Africa, the word turned it into the Vaderland, the word renamed it at CODESA and perhaps in the words of Makhafula, Azania shall be resurrected. Concerning Blacks is by and large a gut-wrenching account of the story of the unfree born free, it is the tale of a rainbow nation where the rains fall no more. It is about the children who never forget, the ones who know that the shaking of hands and sharing of teacups at World Trade Centre in Kempton Park was only the beginning of the lifelong betrayal that would lead to the fires of Marikana and Braamfontein. The question is, does Black life matter? It is in fact the peculiar conundrum of whether Black life should matter when the very Black bodies that house this Black life are wrestled to the ground, naked, being beaten and battered and evicted from their homes, in Khayelitsha, amid a pandemic. In occupied Azania, the matter of Black lives and whether they should matter is indeed a peculiar matter. Concerning Blacks reveals the vacant spaces in conversations about colonization, democracy and apartheid. It exposes the festering wounds that are covered up by the world cup wins and moments of euphoric amnesia and it shows us the ugly underbelly of this dreamy rainbow nation. Ours is a tale told simply by the unspoken truths between the untrue utterances that came with this democracy. Uit die blou van onse hemel: our forefathers welcomed guests to steal kill and destroy their land and their humanity. Uit die diepte van ons see: we are killed for fighting for the harvest of the land we plough with difficulty. Oor ons ewige gebergtes: our masters live in unending comfort while we fight tooth and nail for the falling crumbs at the feet of these high hills. This is the state concerning blacks in the new republic of old habits. It has often been said of the black: that they are meek, quiet and dormant but beware the day they tire of humiliating humility, for that shall be the day they burn away the evidence of their oppression to give rise to a new kind of normal. Never sleep on us, because while the privileged forget about our wretched existence we are constantly reminded that a time must come where we change matters, that are concerning blacks.

*Catch the launch of Makhafula Vilakazi’s Concerning Blacks project at The South African State Theatre on Saturday 15 May at 15:00. Tickets: R100 at Webtickets & Pick N Pay.

Get tickets at Webtickets