For over two decades the Democratic Republic of Congo has seemingly been deemed ruined. Ravaged and torn by what appears to be perennial war and disease to its populace, it has become a land that anyone who sees no means of profiteering fears or flees. By 2008, the war and its aftermath had caused 5.4 million deaths. Moreover, in June 2022 the Norwegian Refugee Council declared its situation the world’s most neglected refugee crisis. At least five million people are internally displaced and one million more fleeing abroad.

In 2004 playwright Lynn Nottage visited this land, not for a collection of profits, but that of the narratives of Congolese women. Victims whose voices had been swallowed by the harrowing horrors of gunshots. In an interview with critical-stages writer, Nottage shares details of the stories of the women. The first was Salima. Still in search of her four children and husband, Salima recalled her experience of being wrongfully imprisoned by men seeking to arrest her husband. She was beaten and raped, only to find her family abducted after she managed to bribe her way to freedom. It is this horrifying and gaping tale, along with many others of its kind that led the stitching together of her Pulitzer Award winning play, “Ruined.”

“I found my play Ruined in the painful narratives of Salima and the other Congolese women, in their gentle cadences and the monumental space between their gasps and sighs. I also found my play in the way they occasionally accessed their smiles, as if glimpsing beyond their wounds into the future.” - Lynn Nottage

In Ruined, Nottage lodges us in a bar-cum-brothol near the tropical Ituri rainforest, in a small DRC mining town. The barkeeper is Mama Nadi (Hlengiwe Lushaba-Madlala), an attractive woman in her early forties with an arrogant stride and majestic air. The bar aims to work as a cover for the brothel. It is however the brothel that is the cover – a complex ironic kind – a cover of an assuaging refugee camp for women who have fled from being spoils of a war they did not choose. Mama would never admit to this of course; she is running a business after all. She has no care for the war, it is her apathetic and unallied neutrality that has kept her business booming.

An integral part of Mama’s business is Christian (Anele Situlweni), a salesman who provides Mama with anything from cigarettes, condoms, to a new stock of girls. The play begins with Christian bringing Mama new merchandise, this includes two women seeking refuge — survivors of the atrocities of this war. The first is Salima (Shoki Mmola), a woman who was abducted and raped for 5 months, to later be discarded by her husband and family at her return. The other is Sophie (Fulu Mugovhani), Christian’s niece, who was brutally raped by soldiers to a point where she’s no longer able to ingage in intercourse. Both women are avowedly deemed ruined.

The other non-soldier we spend significant time with is a jewel-broker, Mr. Harari (Vaugh Lucas Callawayri), the only stone that survives when the ground is burnt to its element. He has given another of Mama’s girls, Josephine (Sami Maseko), the impression of a treasure beyond this refuge.

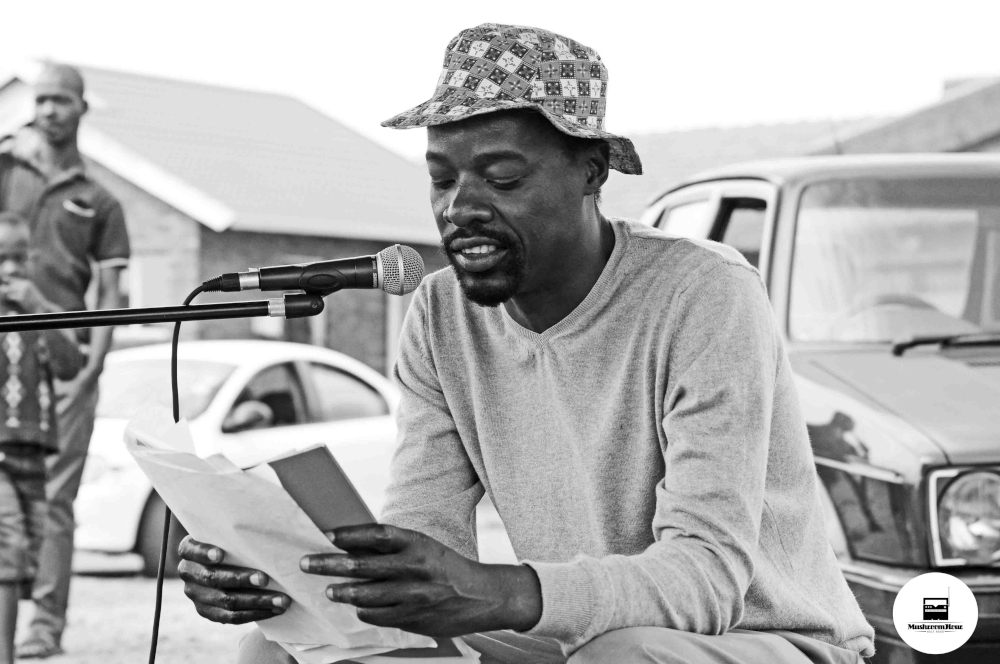

Ruined premiered at the Goodman Theatre in Chicago, and won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Its staging at the Market Theatre in the directorial eye of Clive Mathibe was a machete recklessly racking the evocative narrative of this play. The swing at the accent work by the cast missed the target and joined in on the slaughter; cringe worthy to the audience at most. The effect of which was a betrayal of what could have been brilliant performances from a few of the cast. Molefi Monaisa’s depiction of the mercurial and belligerent Commander was an overbearing sheer example of over-acting, mostly in attempts to compensate for the accent. There are plenty a capable accent coaches in the country, it’s a wonder why this route wasn’t taken.

Mathibe failed even the pertinent and carefully constructed set design by Karabo Legoabe. The play unfolds over a period of 4 months. However, the transitions were clumsy, and the use of the set and props immature and clustered; the audience was almost always lost. We never knew when one day began and another ended. There were even scattered peanuts on the floor and an empty beer bottle on the pool table throughout a 4 months time lapse. How? Even the costume was illused. Amongst many costume mishaps, at some point Christian had his shirt in the exact same shrivelled position for days — an actor's choice that needed the director’s eye.

The opening scene gives a juxtaposition of passion and war, with silhouettes of dancing women on upstage right and marching soldiers on upstage left; this choice was abandoned as the play progresses. The pool table action on stage right, if it called for any attention, was forced and artificial. There was a scene where the bar area on stage left, which served as the entrance to Mama’s pub, moved to centre stage, and Salima’s husband standing in the rain. Besides its faulty positioning, there was nothing apart from the soundscape that indicated the pouring of rain; the actor was utterly unbothered. It could have perhaps worked better if the director took the choice of the rain being a metaphor of the rain of bullets in the war, and the soundscape being that of resounding gunshots.

We didn’t get to fully experience the lighting design of Hlomohang Mothetho because of the unwarranted chaos. It’s only when Salima gave her heart-wrenching monologue that it was inline with the narrative; at most points it was fighting for its position in the play.

I ache mostly for a significant symbolic element that was completely collapsed — the caged gray parrot. The parrot is powerfully introduced in the opening scene; its role set to flight almost. When Christian cracks open a few peanuts and playfully pops them in his month, the parrot squawks. He spots it and the conversation ensues:

Christian: What’s there? In the cage?

Mama: Oh that, a gray parrot. Papa Batunga passed.

Christian: When?

Mama: Last Thursday. No one wanted the damn bird. It complains too much.

Christian: What does it say?

Mama: Who the hell knows? It speaks pygmy. He… Old Papa was the last of his tribe. That stupid bird was the thing left for him to talk to.

Christian: (To the bird) Hello.

Mama: He believed as long as the words of the forest people were spoken the spirits would stay alive.

One would believe that this introduction would at the very least uncage the role of this bird, that its symbolism would somehow plumage the wings of the plot; but alas, the only other time we hear from it any screech, crackle or squawk in this brawling brothel, throughout a period of over 4 months, is at the very end. I question what was actually more substantial, the nuanced impeccable performance of this nugatory parrot or that of the astounding ragtag rebel soldiers?

Mathibe was merely following the script, but certainly something different was required. The production is two and a half hours long with an interval. This would however not be an issue in the hands of a capable director in this play. This propulsive, engrossing story is compelling enough to keep the audience engaged throughout.

It would be an injustice, to leave out the extent in which Lushaba-Madlala held the play together. Her juggling of the blade-like Congolese accent took very little away from her fulgent performance. Her winding timely offers gave flight to the plot and cast alike. She embodied Mama Nadi in every guffaw, sigh, woe, silence, and choler. A masterful lead performance.

Despite its unsavoury staging, as a story that unpacks the relationship of Congolese women with the war, each other, and the complicit parties at the periphery, the words Nottage has spoken into this forest of warfare in Ruined keep the spirit of these women alive.

Ruined runs at Market Theatre until 4 September 2022.