“It was a job you know? Wouldn’t you have done yours had it been yours?” He asked with his old redishly staunch eyes sharply glaring at me.

Of course I would have done my job, I just did not want to give him more ammunition and approval so as to say what he did was right. There is a huge and dangerous gap between doing something because you are being well remunerated for it and doing it because you have some strong belief that doing it contributes to some greater plan of change. That something was indeed something. And it changed.

“Look,” he said after what seemed like forever, his cranium muscles sticking out. “I am not sorry for doing my job. But I do acknowledge the hatred that came with it.” I wondered whether he was sorry for himself or for all of them.

I was imprisoned at Johannesburg Central Prison for eight years, between May 1976 and July 1984. “Nummer Drie, vyf, vyf, nul BESOEK!!” I can never forget the sound of that. I was prisoner number 3550. I still am in a way. Political prisoners we were called in those days. Now I work as a grease monkey in an old beetle hiring company. Privileges were limited for us blacks as opposed to other races. I suppose we were deemed the most evil and dangerous thus, very much unwanted. Derik and I now work on the floor side by side, both with a common goal, satisfying the company’s clients. How ironic.

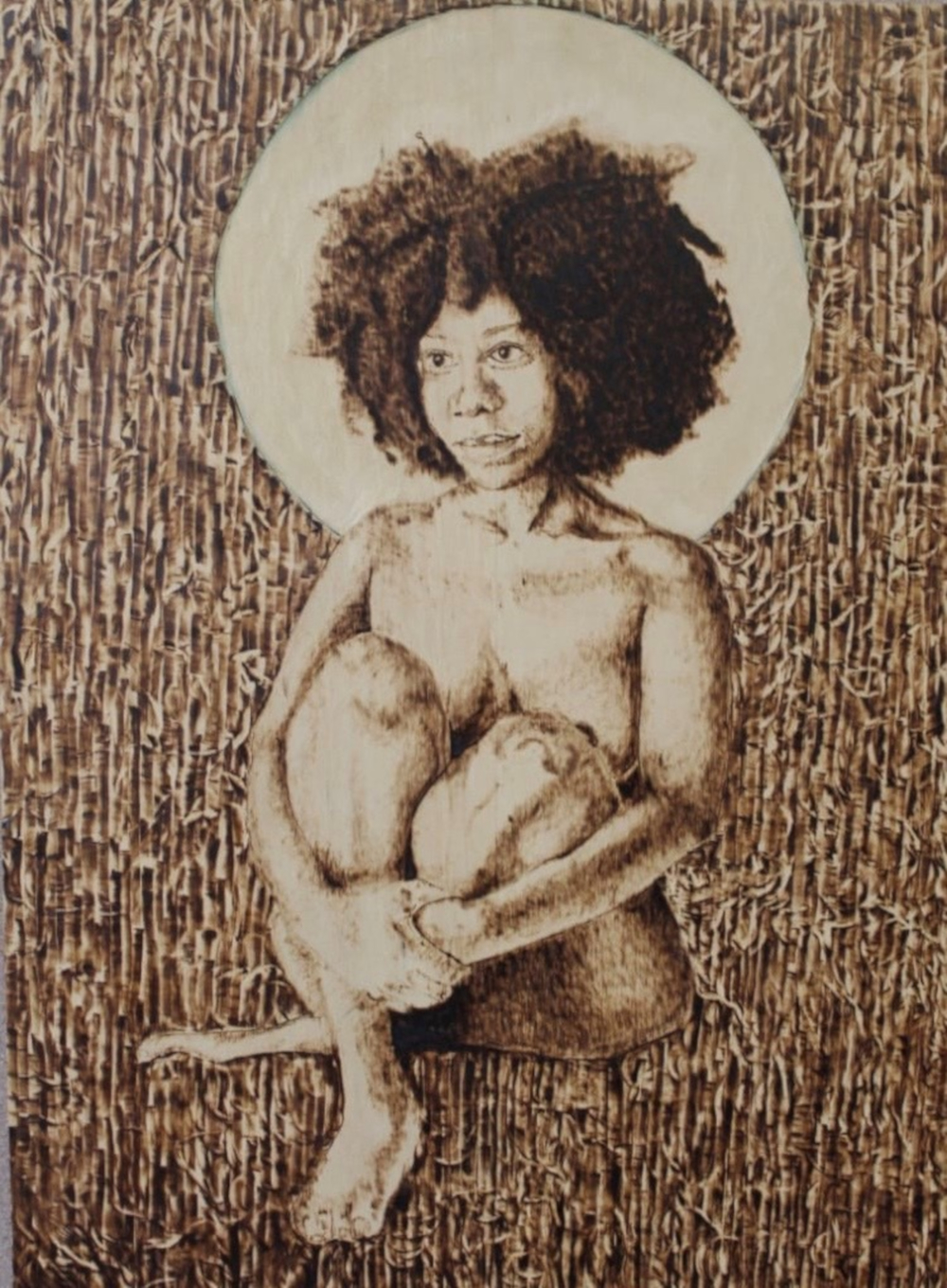

It is winter of 1976; violence looms in township streets, where ever you go you can smell it, children as young as nine years walk the streets day and night, they patrol, they go hiding for days and they grow up quicker than they should. The streets are misty from smoke derived from burning charcoal and the dust from dry weather. The so-called tin houses are housing hunger and anger, individuals living as a collective, one for all and all for one. A brother is not only someone related to you by blood, but by a common yearning, freedom.

A police station is targeted for a bombing following a tip off that it is housing some documents with devastating information on some of our key personnel in the organization. I and a few other comrades are then tasked with bringing it down. Everything had gone according to plan up until this last minute. It turns out that the information was relayed by an impimpi (informer) to set a trap for us; the twist though was that those who were expected to carry out the mission were not the ones tasked. It had all along been a Secret Police gig. They knew that on finding out about this information, we would react and try securing it, obviously falling into the trap, and we did. There were four of us, charged with treason.

They let us torch the place, watching from a distance and when the deed was done, I heard Klaas say, “Lezinja zisipimpile! Abosathane!” these dogs snitched on us, devils! He was the oldest, most wary and experienced among us, he’d left high school a year before to pursue a career in freedom, he used to say. So the rest of us joined in a year later. It was my second year officially in the struggle. I saw it hopeless to continue studying only to end up working as a garden boy or God knows whatever other shit those fuckers had in mind for us! Before I could even look to make sense of what was going on, a baton made a zombie of me. I was hit. Hit hard on the head. Klaas and I were caught instantly on the spot; Juba never even made it into the big Tambayi (apartheid police vans were known as tambayis). He was shot on the back of his head, the bullet gashing his head slightly apart. We heard his funeral was even tougher to bear. Simon was brought in later, beaten up to a pulp. He ran and I suppose that was the consequence of making them run after you, they beat you up good. So that was it, we were never to see our families for a long time but we did not know this, we had hoped that we’d get off with a warning somehow.

![1976 [Part 1]](http://culture-review.co.za/images/logo.png)

![1976 [Part 1]](assets/images/1976.jpg)