My ‘Master of Arts (MA)’ dissertation as titled above, inquisitively probed for ‘Africa’s Contribution to International Relations Theory (IR)’. Rationale for this study was that as a ‘black’ South African student, who completed my undergraduate (2002-2005) and honour’s (2006) degrees, at University of Zululand (UZ), one of the ‘Historically Disadvantaged Universities (HDI’s), with Political Science as a major, I (along with fellow ‘black’ South African class mates) realized that we were hardly taught, about ‘black’ South African Political Scientists. Oddly the aforesaid status quo incredibly prevails to date, in most institutions in South Africa. Why? Well unbeknown to our credulous buddying minds back then, we overlooked that the bulk of our lecturers, were also colonised graduates, hired from other South African universities. To be specific, the two lecturers who taught me Political Science, were namely alumni of Universities of Pretoria (UP) and of Durban-Westville (UDW) - now University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). As regards race, my two aforesaid lecturers, were descendants of Afrikaners and Indians.

My aforesaid lecturers were (albeit differently from our ‘black’ South African graduates), also victims. Their flaws however were consistent, with the historical path imposed from a common inheritance, informed by racial prejudice. Indeed in the context of post-1948 South Africa, owing to Apartheid’s misconstrued policies on education, indoctrination was officialised and implemented, on the strength of the recommendations of the ‘Eiselen commission’ of 1952, which justified the dogmatic agenda, favourable to Afrikaners. Needless to say the latter were pursued, at expense of scholarly objectivity. The latter dynamics may perhaps elucidate, why my lecturers did not realize the agency, of revising contents of modules, which did not prioritise teaching us equally, about both ‘black’ and ‘white’ South African scholars, alongside those from abroad. They could have pursued the latter, from foundation modules, such as ‘Introduction to Political Science’.

As one may have expected, as a postgraduate student of Political Science post 2006 in South Africa, the latter incongruence worried me enormously. I found it baffling that the discipline of Political Science, as taught in South Africa, reflected a critical gap of a ‘lack’ (persisting to date) of most insights of ‘black’ Africans. My special interest, was expressly on ‘black’ South Africans (located in Africa or beyond in the diaspora). It is such details, which inspired my research. In brief on the advice of one of my interviewees in my honour’s study, Dr. Manelisi Genge, the then Chief Director of the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) in 2006, the forerunner to the present Department of International Relations Cooperation (DIRCO), I enrolled in 2007 at Stellenbosch University (SU), to investigate the above questions. Attention thus progressed, from the broad field of Political Science, to the specialized focus, placed on International Relations (IR) and International Relations Theories (IRT). For the record my MA dissertation under discussion here, expounds the distinction of concepts such as ‘IR’, ‘international relations’ and also lists a sample of the theories that form part of IRT. Owing to miscellaneous dynamics, both related and unrelated to the progress of this study, it was eventually discontinued at SU in early 2010, in favour of immediately resuming it, in early 2010 to 2012, back at my alma mater at UZ.

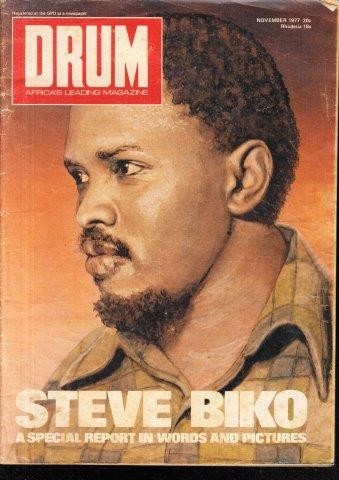

The aim of my study, was to explore for ‘African contribution to IRT’, so effort was initially placed on the literature of IR and IRT. Consistent with the ethos of exploratory research, attention was also placed, on African scholarship. The latter explicitly refers to the field of African Philosophy, with a particular focus on literature, concerned with the discourse of ‘Afrocentricity’. Afrocentric discourse inspired this study to hypothise, that the obscurity of African scholars and their insights in IR and its theories, may suggest that African contribution to IR and IRT possibly exists however has been marginalized, mostly because of not being necessarily similar, to what has been accepted, as part of core or mainstream IR scholarship. Owing to the explorative nature of the investigation, the selected methodology of the study, was categorized as falling under ‘qualitative studies’. Value of this study was opined to have lay, in its possibilities from an Afrocentric premise.

Findings and Recommendations of the Study

First the extensive attention placed upon the body of scholarship of IR, reflected how much IR suffered as a result of being one of the intellectual descendants of Western Philosophy. This meant that IR, as one of the branches of Political Science, suffered from being a parochial (Eurocentric) and ‘white’ male gendered discipline. This meant that IR predominantly featured ideological thoughts, of Western male scholars. Notably the latter priviledging of Western scholars and their insights, supported that IR’s failure to acknowledge inputs, beyond Westerncentric insights, made it a racist discipline. As part of recommendations of my study, present and future scholars of IR were advised, to dare to also explore the strength, of the unconventional Afrocentric approach, when investigating for African insights to IR. Ultimately this study, was able to reflect, the merit of its hypothesis, that African contribution to IR has always existed yet it has been marginalized.