The year is 1990. President F.W. de Klerk announces the beginning of the end of apartheid, the release of Nelson Mandela and other political prisoners, and the end of the South African state of emergency. The African National Congress's armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, suspends its armed actions after 29 years. Charles J. Fourie premiers his play The Parrot Woman, at the Market Theatre, Johannesburg.

Approximately 90 years before the staging of The Parrot Woman, the Boer Republics were at war with the British Empire, following the colonial administrations' discovery of gold deposits in the land. Land “belonging” to various African polities; there was a conflict in a region where four-fifths of the population is Black. The Blacks were abject. The war was white. The British prevailed.

Through scorched-earth tactics, destroying Boer Farms, including crops and livestock, the British forcefully led tens of thousands of women and children into concentration camps. This war is the backdrop to Fourie’s 1990 version of The Parrot Woman. The concentration camps are his setting. A British soldier and a Boer woman prisoner are the characters.

This version was a tale of a Boer woman (Christina) held captive in a concentration camp for the murders of her husband and children. A British soldier (Venter) with Afrikaans lineage is given the task of guarding the woman. He is a mixed breed. She is mad. The British found her on her farm, disconnectedly staring at an African Grey parrot in its cage, rifle in hand, and her husband and children’s dead bodies still warm in the other rooms. She is kept in a cage while awaiting trial, where she observes and echoes the goings-on around her – very much like a parrot.

The unfolding of this period piece unveils a love story. The British soldier and Boer woman prisoner share their life experiences. They find common ground — a connection. They fall in love.

Down the barrel of one gun, there is a tacit philosophical identity divide, found beyond the outskirts of the text. With the notion that at a time when the “Black nation” of South Africa was seeming to be getting into power, it would only make sense for there to be a play that speaks into the “white nation” putting their differences aside, coming together and finding common ground. This however gives an idea that the writer wrote the play with an idea of blackness in mind, which may not be the case.

Down the barrel of another, The Parrot Woman is a play that induces compassion and a feeling of pathos without having to cross any philosophical identity divide. It’s a story about othering and the perils thereof. The othering of criminality and that of madness. The woman is a murderer, but a murderer who has killed a murderer. The play unpacks the motives of a murderer, trying to understand and empathise with the compassions of the other, the one who is outside the norms of morality and legality, and trying to understand someone who is the other, like a parrot. The soldier is British with a Boer father. He did not want to choose a side. He’s an outsider. He chose a side. He’s a traitor. He’s the other.

The year is 2022. The African National Congress has been the South African ruling party for 28 years. The Economic Freedom Fighters hold 44 seats in parliament and lead the conversation on the redistribution of land in the country. 72% of South African land is white-owned, with blacks owning only 4%. The Queen of England, Elizabeth II, has died. Charles J. Fourier’s return of The Parrot Woman, is running at the Market Theatre, Johannesburg.

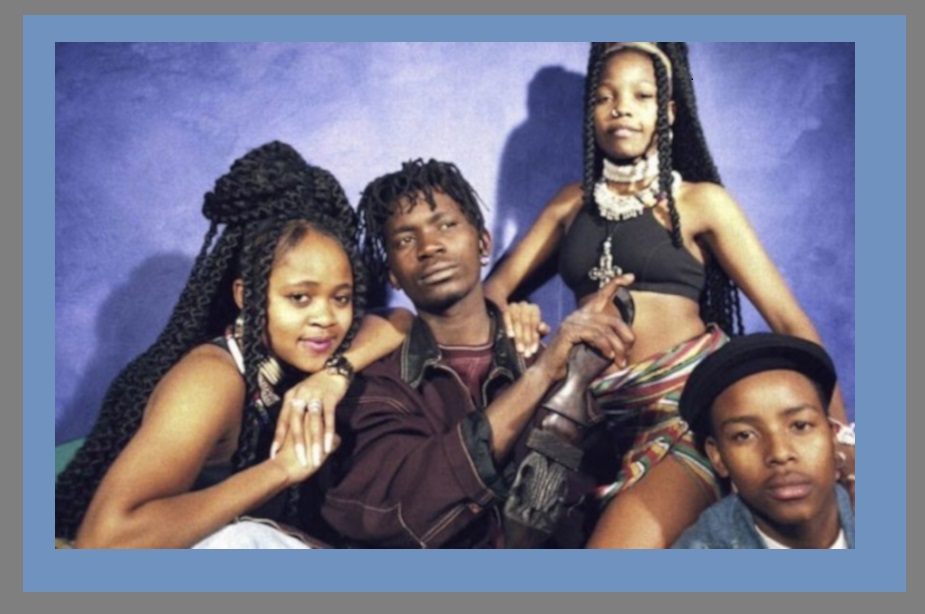

In this new version, Fourie introduces a Tswana woman, Itatoleng (Gontse Ntshegang), who becomes a substitute for 1990 Christina. Itatoleng is found on a farm with the dead bodies of a Boer farmer, his wife and children. The other primary elements of the play remain the same as the original.

The play had seen more than 20 productions at festivals and theatres in South Africa and abroad, with the original story that had no inclusion of the black side of this white war. Fourie aimed to change this narrative with the rewrite. The play not only has a black woman character and sprinkles of SeTswana but also nudges on the South African land issue.

VENTER: What is that damn language you speak?

ITATOLENG: It is my mother tongue. (REPEAT TSWANA)

VENTER: So you not a Boer?

ITATOLENG: Do I look like a boer?

VENTER: No - you look like a mad African something.

ITATOLENG: Like my papegaai . . . he is African Grey like me.

VENTER: STOPS FEEDING HER. That is what it looks like in Ingeland. Grey. That is in London. It's grey and pale. Not like here. Light’s not as bright. And there’s not as much space.

ITATOLENG: Is that why the khaki's want this land?

VENTER: I don't know why the British want this land.

ITATOLENG: Then why you fighting? If you don't know?

VENTER: RISES AWAY. Have you had enough to eat?

ITATOLENG: The English want this land, the Boers want this land. Everyone wants this land. Show me what it looks like?!… To want something so bad you will kill for it? Show me!

The advancing of the narrative of a 23-year-old play to fit the current time, ought to be applauded. However, Fourie simply gave Christina black skin and a few Tswana words and called that writing a black woman into the story. This in itself was the blindfolding of his multi-award-winning play, only to shoot it point blank by poor execution. His shot at relevance ricocheted to injure what was a splendid narrative, and performance in the play.

Who is Itatoleng? What’s her story outside of the farm and her sexual relationship with her Baas? How did her life and that of her family fit into the war? What are the defining factors that led to her madness? How would we describe her personality and identity? These and many others are questions not answered in the play. Blackness is an adject, not even a thought. Fourie brings it in as an afterthought. It’s the same story; no difference. Itatoleng is not a black character, the black can not be brought into the story or over a role of a white character, they are not in the world of this play.

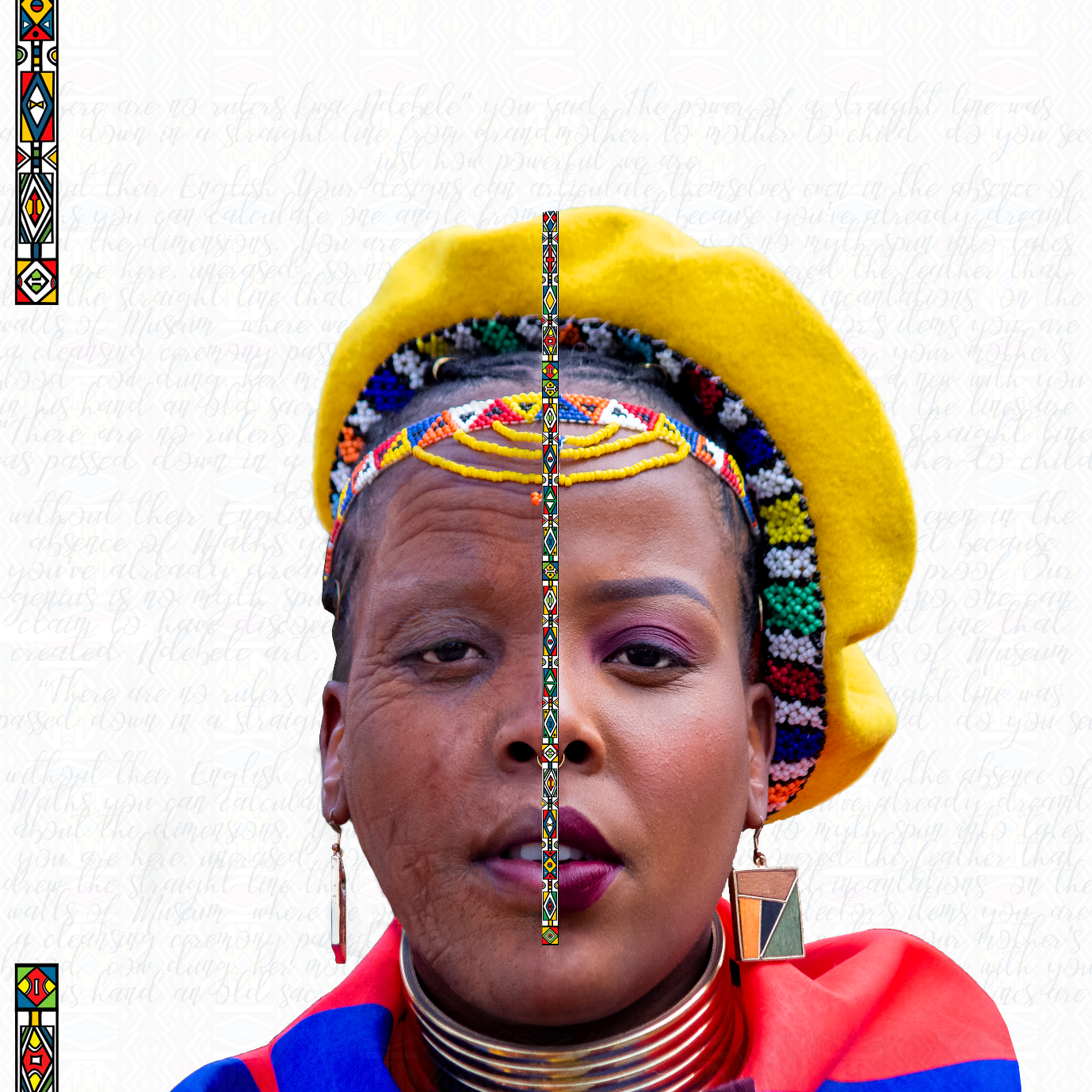

As South African scholar, Ndumiso Mdayi argues, “The black is not entirely even an object, but an adject. Objects are either pushed to the limits of their subjectivity or refused their subjectivity through imposition of rule, but, in [this] world, the lack of subjectivity of blacks is necessary and functional.” This is the world of Fourie’s play, a world where Itatoleng is an adject. Never part of the relationship. Simply external.

In his book Slavery and Social Death, Orlando Patterson asserts that the construction of blackness in a slave context is the construction of social death, meaning that if you’re black you’re dead socially, you’re outside of social relations. Blackness means non-existence in all ways, non-existence in social relations, and therefore non-existence even in thought. Itatoleng did not cross the psychosocial divide between existence and non-existence.

Moreover, if a play fails at anything, let it at the very least succeed in its suspension of disbelief. Fourie shackles disbelief to the stage and parades it ever so dexterously. From Venter (Andre Lotter) smoking a pod vape, a 2003 invention, to him gifting Itatoleng with a tampon, when tampons were invented in 1931. Even the use of the vape itself was limping. Fourie attempted to create a moment with Venter blowing smoke into a campfire, but that moment was a mere short-lived ephemera; what about the other cold nights, was he not in need of warmth, why did he not light the fire again? How were these props overlooked for an 1899-1902 period piece?

Are objects in a play not meant to be plot devices that march the story forward? Indicative of Anton Chekhov’s “The Seagull”, Venter points a rifle at the audience in the opening scene, and in the last scene, Itatoleng attempts to commit suicide with it. The downfall, however, is that the ethos of Chekhov’s Gun is, “One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off”, an ethos that is a blank in Venter’s rifle. This device thus could have perhaps been the thread throughout the play, stitching closed any wounds inflicted by the weakened narrative. It was introduced as inimical and threatening, and Venter was meant to be the extension of this macabre object. Alas, his performance exposed the rifle to be fake, holding no threat whatsoever. His embodiment of the austere yet sensitive character of Venter was both poor and banal.

At its core, the script is a love story. We however do not get to experience the development of this relationship. The performances of both actors shield the audience from journeying with the characters from soldier-prisoner to allies to lovers.

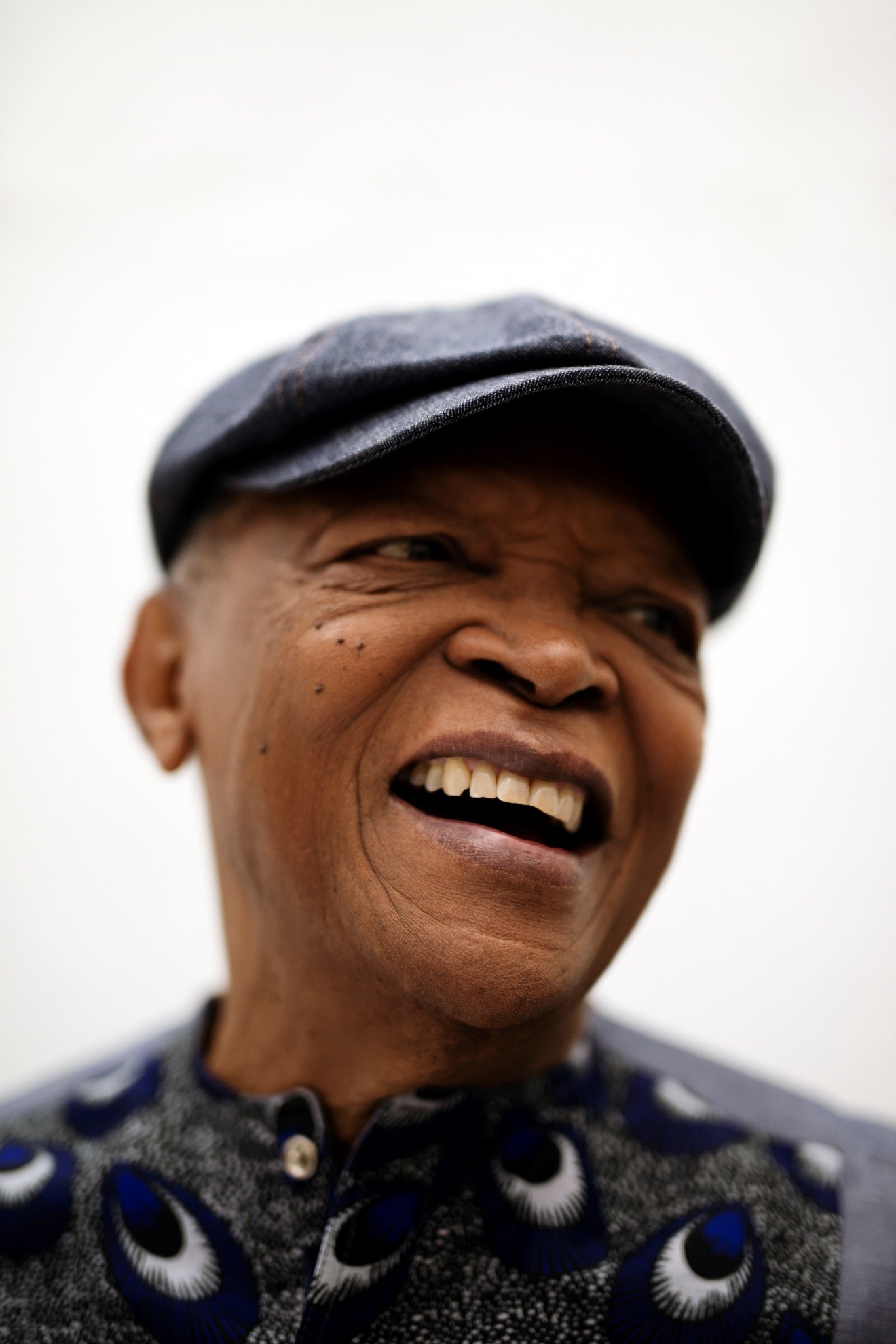

Perhaps this speaks to the lament of the casting of actors who predominantly work in television in a country with scores of experienced practising theatre actors. In a Morning Live interview Lotter shared, “We did a lot of… Well, that’s my first experience in terms of theatre, we did more of an exploration and experimenting in the rehearsal process”, a shock, as workshop theatre has been an integral part of South African theatre.

Being stationed in a role meant for a black woman in a white story, it was quite incumbent on Ntshegang to deliver a stellar performance. Her physical and vocal ability assiduously bandages the story. Ntshegang most certainly carries the play, though mediocre moments were not far and few in between.

It is by no means a blunder that The Parrot Woman is a multi-award-winning production. Jade Bowers’ set paired with Wesley France’s lighting design gives a very real and interesting visual experience. The writing on its own is compelling, with the phrase, note and pulse of the text allowing a pace that lands the story deep in the hearts of the audience. Despite the mishaps, it is most certainly a product worth a theatre visit; if not for its enjoyment, then perhaps for the timely conversations that hurtle from it.

The Parrot Woman runs at the Market Theatre until September 25 2022.