Such a great pity that the weather could not be governed. The Mayoral Committee had been planning the thing for a whole month, but as soon as the week of the well-funded occasion began, rain, heavy and non-stop, poured down for days on end. The bridge, whose ‘opening’ was the reason for the planned celebration, was impassable from the Wednesday right through to the Saturday of the event. Rain being the cause for the bridge becoming uncrossable was not, in and of itself, a development that surprised anyone who had set eyes on the structure upon its completion. It had been clear to even the most hopeful observer that heavy rain would render the bridge unusable. In any case, some important personages had been invited; had confirmed their attendance after much sustained lobbying; a fortune had already been paid to a ‘distant’ cousin of the mayor for the provision of Oros and scones, and the bridge was at any rate visible from the patch of ground upon which a makeshift podium and shaky marquee had been erected on the day.

As such events tend to go, each face in the crowd wore a look of practised expectation. It was important not only to be there, but to look like one was very glad to be in attendance. The crowd itself had exceeded expectations. About a hundred and fifty, from a projected one hundred. Up on the makeshift podium, the dignitaries sat with a surprisingly solemn air, perhaps betraying the fact that, the day’s joyous occasion notwithstanding, they were people who were constantly bogged down by concerns of public office possibly much weightier than the present circumstance could lay claim to. Not to take anything away from the day, however. It wasn’t every day that officials from national government accompanied the mayor, and indeed the opening of a new bridge, all three and a half metres of it, was an even rarer occurrence in these remote parts. Food and drink were rumoured to be in plentiful supply, but listening respectfully to several speeches was the price the grumbling stomachs would have to pay for their keen interest in the customary refreshments to follow.

A poet, who had chosen as his theme the achievements of the ruling party, stole the show when, at the end of his poem, he got the crowd to chant along with him, ‘Come and see / Come A and come B / Oh come and see / Come C and come D / Oh come and behold / what the Congress of old / has done, has done’… many times over. A popular drunk who everyone called Bra Zest, who never missed these kinds of events, sprang to his feet and fashioned some kind of dance as this mantra was taken up, but the widespread appreciation of his spontaneity was dampened a little when his exertions elicited a loud fart from the crevice in his raggedy-overralled buttocks. Some people laughed good-naturedly, some jeered uncharitably, but the look on Bra Zest’s face did not stray from the glee with which he had trained it.

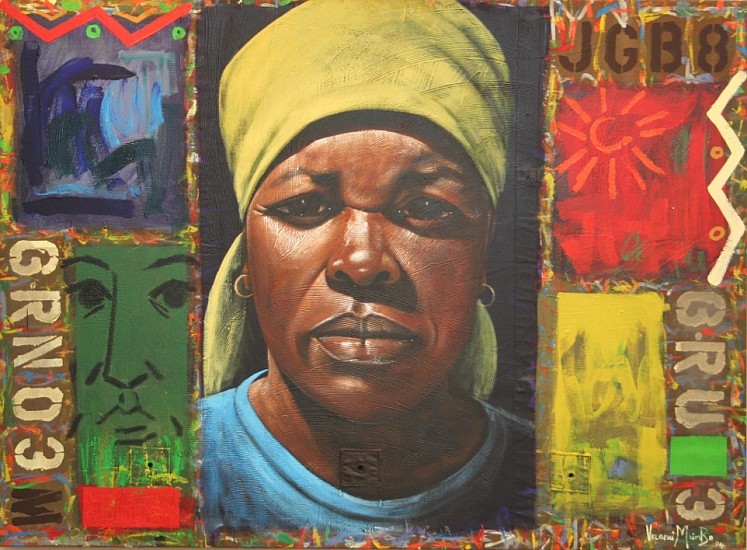

It was then that the Minister of Public Works, moved no doubt by this impassioned mantra and the crowd’s bellowing of it, personally got up to thank the poet; handing over to him what looked like a thin wad of notes. This gesture, carried out with the kind of crouching movement that suggested the transaction could be done in secret, even though it was performed before such a throng of onlookers, instantly set the crowd abuzz. The news which now spread through this gathering quickly formed a whispered but widespread consensus; the notes had been of the R200 denomination. Some prayerful women in the crowd, bringing their hands together to clap for this act of generosity, also let fly some glories and some hallelujahs. Ma Edith Mwelase, her elaborate headgear marking her out in the crowd as one of the more distinguished attendees (who were not however up on stage), nonetheless staked her claim to belonging more up there than in the dust of the jostling bodies down below.

‘He is like that,’ she noted loudly. ‘The minister is like that.’

‘Even last time when we welcomed the Premier, he did just that to a little girl who gave a speech. God bless this generous man,’ she said, fanning herself with a folded-up newspaper as impressed eyes and ears took in her words. Unfortunately, the minister’s generous gesture resulted in the poet launching into another round of his repetitive stanzas, causing the mayor, who was next up on the list of speakers, to frown with displeasure and give the sweating reciter a warning look. In truth, the mayor was more upset with the Minister of Public Works than he was with the beaming poet; feeling that the former’s largesse was a thing that he ought to have thought of first, as someone whose heartbeat was more in tandem with those of the people attending the gathering.

Soon enough it was the mayor’s turn to speak. Feeling like he was lagging behind somewhat on points, he took to his speech with a vigour that was unlike him.

‘God is good!’

And the crowd roared back, ‘All the time!’

‘All the time!’

‘God is good!’

The call and response had become a trademark of the Sundays (most of them) during which he acted as MC at his local church, and he had soon discovered that the thing worked equally well at gatherings of a more secular nature. But the mayor was a man of quick and volatile temper, and the thought of how the national minister had just upstaged him in his own backyard caused him to seethe with rage. He swallowed hard, took a deep breath and looked out through the blurry eyes of one truly incensed.

‘This young man,’ he began, pointing towards the poet, who had now descended the stage and was in the front row of the standing crowd. ‘This young man, you will all agree with me, is one of the most gifted sons of our community.’ There were murmurs of approval and a general nodding of heads. ‘Honourable Minister, it comes as no surprise that you would be so impressed with the young man’s, eh, way with words… In fact, my wife and I were just discussing, just before we came here, when to give him the gift we got him on our last visit to the capital…’

‘Young man,’ he continued, wagging a mock-threatening finger in the direction of the poet, ‘After this you must come to the residence, because your brand-new laptop is waiting for you there.’

There was a momentary hush that fell across the gathering at this instant. Confusion, caused by the fact that the mayor was in fact a notoriously stingy man. But the mayor’s wife stepped into the gap swiftly, before any seeds of doubt could envelop the moment. Almost startling the Minister’s speechwriter, a pretty young woman who went everywhere the Minister went, Mrs Mayor as she liked to be called leaped up from her seat and shouted an ‘Ah! But daddy, we were supposed to give him at church! I thought we had agreed!’

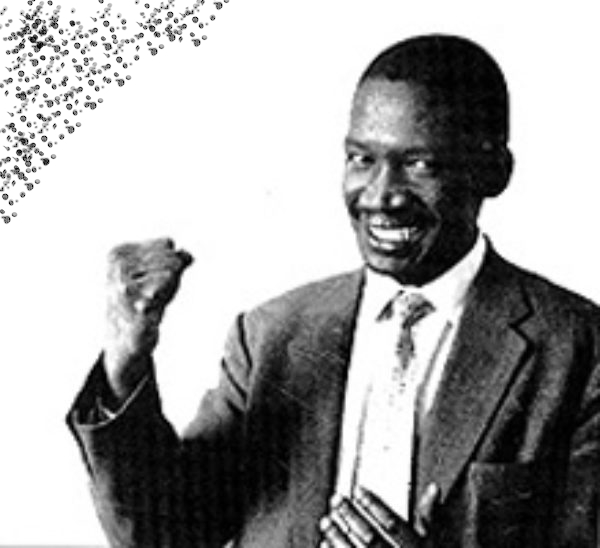

At this, a state of near-pandemonium ensued, lasting for well over a minute. The poet, doubtful and hopeful all at the same time; feeling that even if there was no laptop, there would now somehow have to be one, had shot an arm and clenched fist of jubilation up skywards, whereupon he was seized by many hands and hoisted aloft. This carrying on, making the poet the momentary centre of attention, might have in fact continued a little longer if one of the mayor’s bodyguards had not had the presence of mind to shout into one of the microphones to the left of the Mayor.

‘Put him down!’

The order was given with so much force that the hands seeking to obey did not have time to think about a soft landing for the hero of the moment; so that the poet did indeed land rather awkwardly and put out a hand to break his fall.

‘You see,’ said the Mayor, taking partial charge of the situation once more.

‘Look how you have almost hurt our prized asset, our treasure. Are you people jealous?’

This last was said with a chuckle, and the crowd laughed along at the joke. But the Mayor was determined to deal with this unplanned, unwelcome lionisation of the poet once and for all.

‘First Aid! Where is First Aid here when you need them? Where are these people? First Aid!’

And as the uniformed first aiders appeared, running, from a nearby vehicle, two other bodyguards had already taken hold of the poet and were marching him towards the assistance.

‘Yes, yes,’ said the Mayor in his most soothing voice, feeling for the first time in some long minutes like he was regaining control of the proceedings. ‘Just… Check his arm. I’m sure he’s okay but… Check his arm. This crowd is trying to kill the young man on his lucky day,’ at which joke the gathering again burst into laughter, relieved that their mayor had retained some of his humour and was sharing it with them.

It was this burst of laughter that woke the Minister of Public Works up, for the umpteenth time since he had been offered the red-and-gold-gilded chair reserved for his use on this occasion. He looked around stiffly, self-conscious, because those who awake to laughter often suspect that they are the butt of whatever joke is going around. The Mayor was clearing his throat and saying how delighted he was that a whole national minister would take time off his busy schedule, not to mention travelling all the way to ‘our own little humble corner in this great land, truly, such an honour…’ and so on.

As he spoke, repeating oft-used phrases he had no need to rehearse, the Mayor locked eyes with his wife while turning half-around to acknowledge the minister’s contingent. A fleeting micro-second, but there was no mistaking the questioning annoyance in the glare she shot back at him. ‘How the hell are we leaving here indebted to this boy for a non-existent laptop, and where will we get the thing? You are messing up my budget,’ the look said fleetingly, before melting into warm and motherly enquiry of the pretty speechwriter, if the wind and dust was not too much for her and would she not like a shawl to cover her shoulders and perhaps face? No need for Mrs Mayor to listen to her husband’s speech, she had heard that kind of thing a hundred times before...

As twenty minutes slowly started edging closer to thirty minutes and the Mayor continued to rattle off the achievements of his administration, Pastor Agrippa Khumalo, one of the more aggrieved of the community members in attendance, had found an outlet for his frustration, for he was heard shouting from the direction of the vehicle to which the first aiders had escorted the uninjured poet.

‘Heal! Urrr… Heal! Urrr.. In Jesus name! Heal! Urrr…’ could be heard competing with the Mayor’s monologue, now rattling off numbers and percentages that could hardly have been of much interest to the gathered crowd. How to tell the righteous healer to quieten down was a task that even the Mayor’s bodyguards didn’t seem too keen on. Indeed, Pastor Agrippa Khumalo had every reason to feel aggrieved on this occasion, where, for reasons no one had explained to him and quite against the more-or-less established practice, there were important dignitaries attending a municipality event and he was not one of the personages up on stage. He had the poet in what looked from a distance like a chokehold, clasping him tightly from behind so that the apprehending arm also had hold of the young man’s shoulder, and was shouting his pleas for healing ‘if anything is broken’ at the top of his voice.

‘Heal! Urrr… Heal! Urrr…’ the man of God continued determinedly, and it began to dawn forcefully on the Mayor that a speedy intervention was required.

‘Ah, Mfundisi! My very own pastor!’

Pastor Agrippa’s tight hold on the hapless poet eased a little.

‘Mfundisi, you are here!’ And the offended preacher’s grip on his patient softened a little more.

‘Why didn’t anyone tell me that the man of God is here,’ the Mayor demanded, of no one in particular.

‘Where is a chair,’ the Mayor continued, looking about him on the stage. ‘Mfundisi! Please come up!’

Pastor Agrippa Khumalo let go of the poet, who was now thoroughly annoyed despite the notes bulging in the back pocket of his African-print pants, and began to march quite triumphantly towards the podium.

‘Please take a seat, my father,’ the Mayor implored, as his pastor bounded up onto the stage.

‘This man is my spiritual father,’ the Mayor further intoned.

‘I was beginning to wonder who would close for us in prayer.’

‘But in his heart, which sometimes forgot the necessity for these kinds of strategic alliances, the Mayor thought, ‘This man is very forward. He is getting too big for his boots.’ Still, the Mayor accepted the fact that his pastor would now indeed have to deliver a closing prayer, even though no such item had been planned for the day. It was also whispered to the Mayor by one of his bodyguards, just as he resumed his seat, having finally ended his long-winded speech, that the scones and Oros provided for this opening shindig were looking quite meagre for the size of the assembled crowd.

As his brow clouded over with anger, the Mayor thought quite decisively that his allegedly-distant cousin was a greedy woman who would not in future benefit from any of the municipality’s events and projects. Quite naturally, this moment of annoyance did not coincide with any remembrance on the Mayor’s part that he had pocketed almost half of the money paid to his cousin, which he had demanded she pay into one of his personal accounts on the very next day after she received payment from the Chief Financial Officer.

Pastor Agrippa, when his moment in the spotlight arrived, was not the kind of man to not make full, and even extra, use of it. He began his prayer by observing that the Holy Bible admonishes all good Christians to forgive not only their enemies, but also their friends.

‘You alone know, oh Lord, that we who have humbly dedicated our lives in service to your gospel, have not done so out of any desire to be personally rewarded… or recognised. We are happy to serve in the cause of your great kingdom, but we do so not out of any personal ambition. And I know, my Lord (here he began to raise even further his already raised voice) that it is only your Holy Spirit that would remind a gathering of your children, like this one, that the event cannot begin or even close without prayer. To continue without calling on your Almighty presence to bless us all!’

The Mayor, who had been listening keenly to the direction the prayer was taking, beginning to feel a little discomfited, felt at last now fully attacked. So, this pastor, instead of being grateful that he had been called up to the stage, and been given the microphone for the closing prayer, was still taking digs at those who had dared to not put him on the programme to begin with? But Pastor Agrippa Khumalo was not done. Never one to let an opportunity go abegging, the man of God now turned his focus to the National Minister of Public Works, who was, praise God, in their midst. And he turned his attention on the cabinet minister with the full might of prophecy.

‘My God! My God!’ … The emotion seeming to choke his voice while never for a split second compromising the volume thereof, the impassioned density of the moment causing one of the brethren in the crowd to begin a loud liturgy in tongues, the man’s rich baritone threatening to dwarf even Pastor Agrippa’s shouting, while a woman near him began to wail quite uncontrollably. What with the spirit taking over... These last two caused the pastor to pause momentarily, lest his prophecy concerning the cabinet minister be lost in the ruckus, which seemed to him rather inopportune.

‘My God!’ He began again.

‘It is only with the gift of your blessing, which makes us see further than men can see, that I can say today, in this hidden corner of the country, that we are indeed in the presence of a future president of this country!’’

At this, there broke out a loud chorus of hallelujahs, mixed in with different exclamations of surprise, shock, and awe, in the general assembly. The minister, of course, knew the kind of game that was being played. It was the kind of ass-licking he had become accustomed to, at different times and for different reasons. Nevertheless, he allowed himself a glancing moment of irritation, simultaneous with grinning acknowledgement, with the performance…

Now, if anyone had caught sight of the poet at this juncture, which, fortunately, dear reader, you are in the correct position to do, such a person would note that the fellow was sulking a bit. All attention, you see, had now been removed from him, including the unwelcome ministrations of the man of God, Pastor Agrippa Khumalo. Also, the poet had begun to think very seriously about how he would get the promised, non-existent laptop into his hands. But this is not a story about the poet. Or perhaps it is? I myself am not sure.

Or perhaps it is a story about Oros and scones… Especially because, the plentiful supply of these most basic of the basics were the principal interest of the majority of those in attendance. Unfortunately, it turned out that the Mayor’s allegedly distant cousin had been less than honest in how she had dispensed the ample budget given her. In fact a sense of general disquiet, rising audibly into vocal disgruntlement from some of the braver ones in the crowd, spread swiftly through the expectant throats in this assembly. The scones, being lugged forward into the crowd in large, transparent plastic bags, did not look like they could feed a crowd of fifty, let alone the one hundred and fifty in attendance. The august occasion truly looked like it was headed for a rather inauspicious conclusion.

Even worse, it now transpired that the Oros had been diluted only for the illusion of colour, and not, as the gathered throats had expected, for any sweetness in the taste. Indeed, as the dignitaries prepared to dismount the stage and head towards their impressive motorcades, which would transport them to the Town Hall, where the food prepared would doubtless be of a much superior quality, the disappointment of the crowd in the refreshments that had been prepared for them was palpable.

One can, fortunately or unfortunately, not proceed to the conclusion of our tale without returning once more to our poet, for whom the day’s festivities had began so impressively. He felt strongly, you see, that the promise of a laptop needed to be brought to a speedy finality. Inadvisedly, he resolved that the Mayor’s favourite bodyguard was the person best-placed to assist him in the task. Sadly, his perfectly reasonable inquiry was met with the most unexpected violence. Firstly, he was sent hurtling backwards by a firm push from the man.

‘Why are you asking me? Why don’t you ask the man himself? You need to learn how to relax…’

The thing struck our community’s bard as a great injustice. When he tried to interject with a well-timed ‘But’ things just got worse.

‘Get out of here, you boy!’

The enmity was sealed in this last statement of dismissal. This last act of unwarranted aggression. ‘They think we are nothing, because they are in power. They don’t respect the people.’ In his moment of blind fury, the poet was quite convinced that this assault on his personal dignity, not to mention the sabotaging of his personal prospects and material benefit, was literally the embodiment of this ruling party’s contempt for ‘the people.’ It might not be necessary to go into the fact that the poet was indeed a rather arrogant fellow, given to selfishness, driven by self-interest, and that the events of the day merely brought to the fore certain qualities intrinsic to the man.

Later on, when the poet’s mother came to his backroom, having heard him arrive back home, and asked him how the day had gone, he had to quickly hide the piece of cold steel he had found hidden in the grass, near the non-descript little stream running behind the south-end of the field, some two months back, during a community soccer challenge. He had been cradling the thing, thinking, hey, these bodyguards think they are the only ones with guns. I’ll show this one. He doesn’t know me very well. You can’t push me like that…