What does it mean to be an object ‘in the midst of other objects’ the thing against which all other subjects take their bearing? - Jared Sexton & Huey Copeland

Future Nostalgia is an interrogation of the deep entanglement between the past and the presence. It is a project that seems to reflect the symbology of the Sankofa bird which is a mythical bird that flies forward while looking backwards. Perhaps the importance of the symbolism is that it emphasizes the impossibility of thinking about the present without a thorough reading of the past. This is to say our imagined futures are extremely and inextricably linked with our pasts and presence.

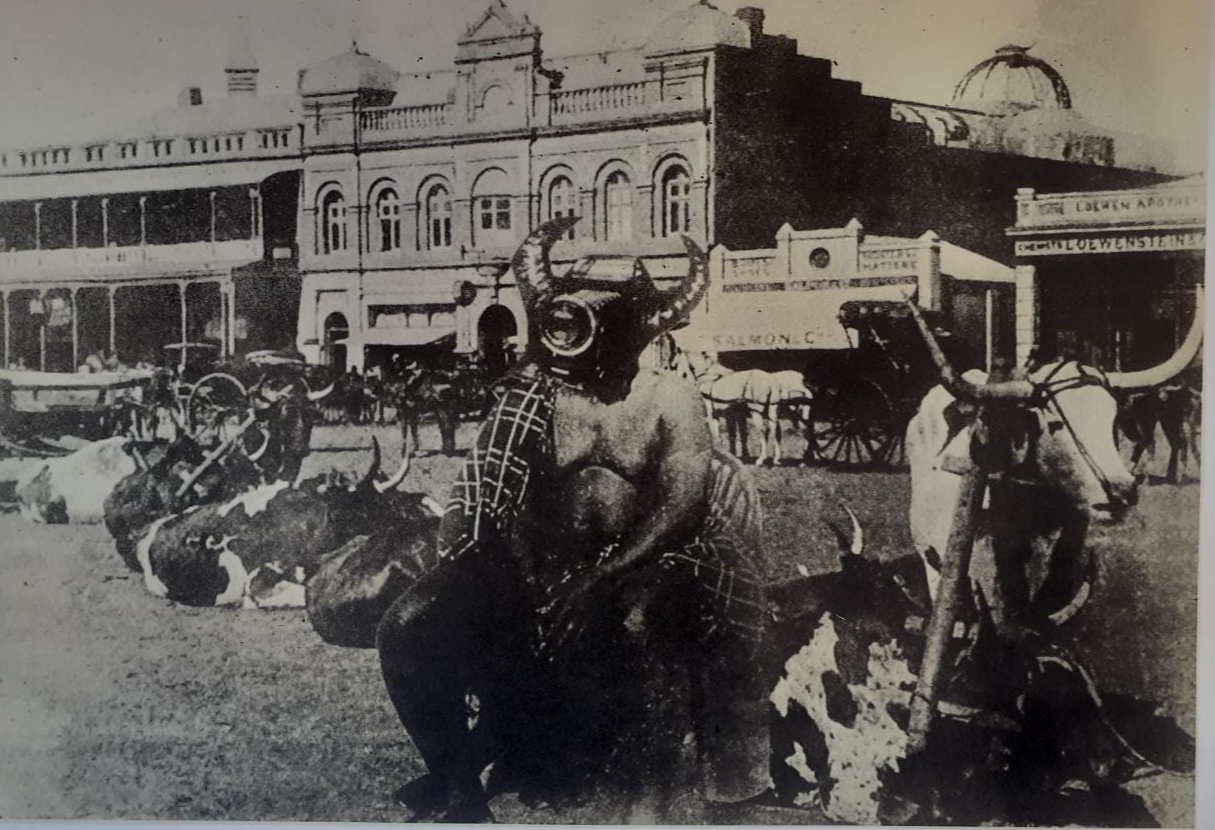

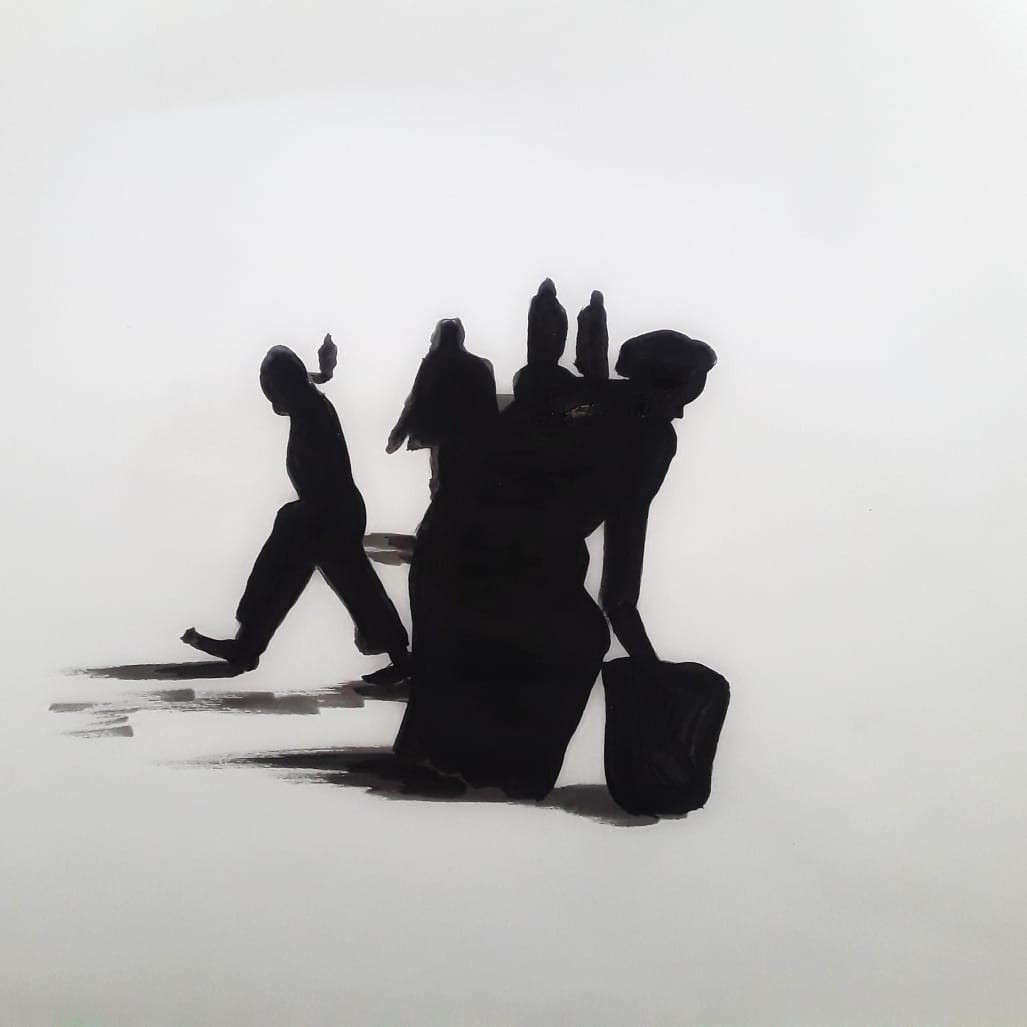

The series is a collage of digital prints that almost immediately reveal precolonial African black men with cameras mounted on their shoulders instead of their heads. The devices which are in the place of these men’s heads seem to be vintage model cameras. On the sides of these cameras horns protrude. Some of the men in the series have precolonial weapons, spears and isagila. The attires suggest that the men are from the Southern region of Africa and although they belong in the precolonial era, they had already encountered with other cultures judging by some of the fabrics that they are garbed with. Although this ethnological reading might be important for others in delineating the series it is not my project here.

The series, it seems to me, does not say anything forthright. Or rather, it is not interested in making statements but gives space for an inquisition of black life and the black experience through time. It is an exploration of the genealogy of the conditions of black people from colonization apartheid and post-apartheid. It seeks to explore whether or not there has been punctuation in the positionality of black people in relation to society. There is no doubt that black people throughout the world have gone through atrocities that were even beyond the grasp of our imaginations. Scholars, artists and intellectuals are still trying to create and forge vocabularies that are going to articulate the terror that black people have gone through.

What better way to express the influence and taint of colonialism than to use the symbology of technological advancement which is the camera. The camera which I argue is one of the instruments that completely altered how people see themselves and how others see them. How we are portrayed and the stereotypes about us were entrenched through the visual, the camera being the instrument. Visual arts are an important art form in that our oppression, blackness is articulated through the epidermal. Remember Frantz Fanon and his first encounter with himself as a black person? ‘Mama, Look a Negro’. It is this looking that I am interested in. How looking determines the distribution and arrangement of pain, pleasure, desires and hopes. The series problematizes the different ways in which looking has been completely racialized. The series although it does not represent whiteness, or the concomitant brutality thereof through the use of white bodies, the use of the camera is sufficient to highlight the race clashes. This becomes more obvious when juxtaposed with black African men carrying weapons.

Future Nostalgia is also located within this tradition of practitioners who are interested in finding ways to represent the black experience in the world and more particularly in the Southern region of Africa. This is to say, Future Nostalgia as mentioned above is a series that is cognizant of the past but not for the purposes of remaining locked in it but such that it can be used to map out strategies for potentialities and possibilities of better tomorrows. At its core the series is asking multiple questions about time and space, rebellion and possibly defeat. It seems that it was intentional, although artists stumble on things, for most of his subjects in the series to carry weapons. Which could symbolize a desire to reject this ‘new’ life, this supposed ‘civilization’ that is represented through the camera. Note also that the camera is located on the shoulders, completely defacing the black subject. Making them completely unrecognizable which means that this ‘civilization’ could potentially or most probably erase the culture and the identity of black people. Truth is, it has. Colonization has replaced all that is our, our black ways of knowing, thinking, and feeling with theirs.

Future Nostalgia provides a lens in which an account of the black experience can be given. There is an existing impossibility of representing race, visually, outside of an entrenched schema that is predicated on the fungibility of the black body. With this knowledge in mind the series is trying to highlight the, sometimes blurry, dichotomies between looking and being looked at, spectacle and spectatorship, enjoyment and being enjoyed. It prompts us to heed the call by Fanon when he said ‘O my body, make of me a man that always questions’. The questioning should never end, so these observations are not conclusive but they are an invitation to look closely and critically at Gerald Khumalo’s prints and maybe the work will force us to ask important questions.