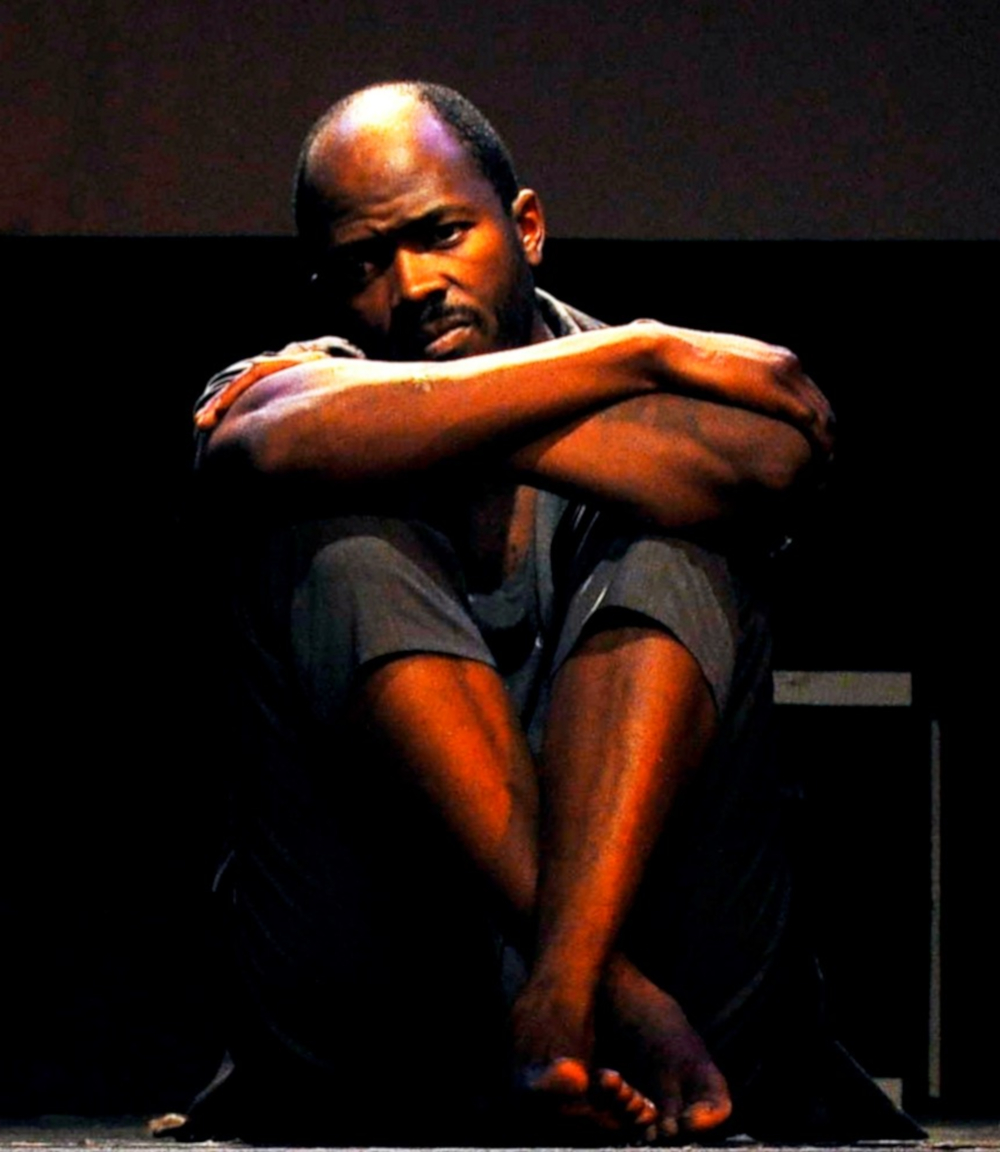

Music has often been able to create dialogic spaces to stage discussions about politics and their relationship with people. This is more so in the case of black people where there is a constant conjuncture between the political and the performative. Black music has always functioned as a lens and as a medium through which we see ourselves and articulate our experiences as a people. Our music is also an important mode we use to communicate our desires and despairs. Through a critical reading of the form and content of black music we can begin to understand or see more clearly our positionality in the world. In 1992 maskandi artists Phuzekhemisi and Khethani released a song titled Imbizo. The song became a huge success with its popularity reaching all corners of the country. Despite its popularity the song was not well received by the chiefs and traditional leaders. The song caused so much commotion that it was subsequently banned from being played by the South African Broadcasting Services (SABC).

On the surface the song was a critique of traditional leaders who would always call meetings (Imbizo) demanding the villagers to pay impromptu taxes such that they could continue staying on the land. The banning of this song happens during a time where most of the artists who were exiled were returning to the country. Mandela had just been released from prison and the mood suggested that the tyranny of apartheid was finally coming to an end. Although there were still pockets of violence and assassinations in the country there was no doubt that the freedom that everyone anticipated was ashore. People were preparing for the coming freedom, it could be seen in the negotiations, in people’s faces, the peace and love t-shirts, and in the many feel good kwaito songs that were circulating the airwaves. But amidst all of this euphoria Phuzekhemisi released Imbizo.

The banning of the song was a gesture, an indication that the devices that were used by apartheid institutions to silence certain views would possibly continue post-1994. Beyond the literal meaning of the song Phuzekhemisi did something unprecedented at the time. He gave a critique of those who were about to be in power at a time where very few were thinking about the posture that a black leadership or government would take. There is no doubt that the maskandi artist was unaware of who Frantz Fanon was but he was able to offer a rendition of what Fanon had termed the pitfalls of national consciousness through his song. Whether he was aware of it or not his song was trying to tell us that those who were about to inherit the country would do nothing but duplicate and mimic the ways of the incumbent leadership. How they would be comfortable with being proxies of white power. He was warning us about how the new government could possibly be nothing more than an extension of white dominion over black people.

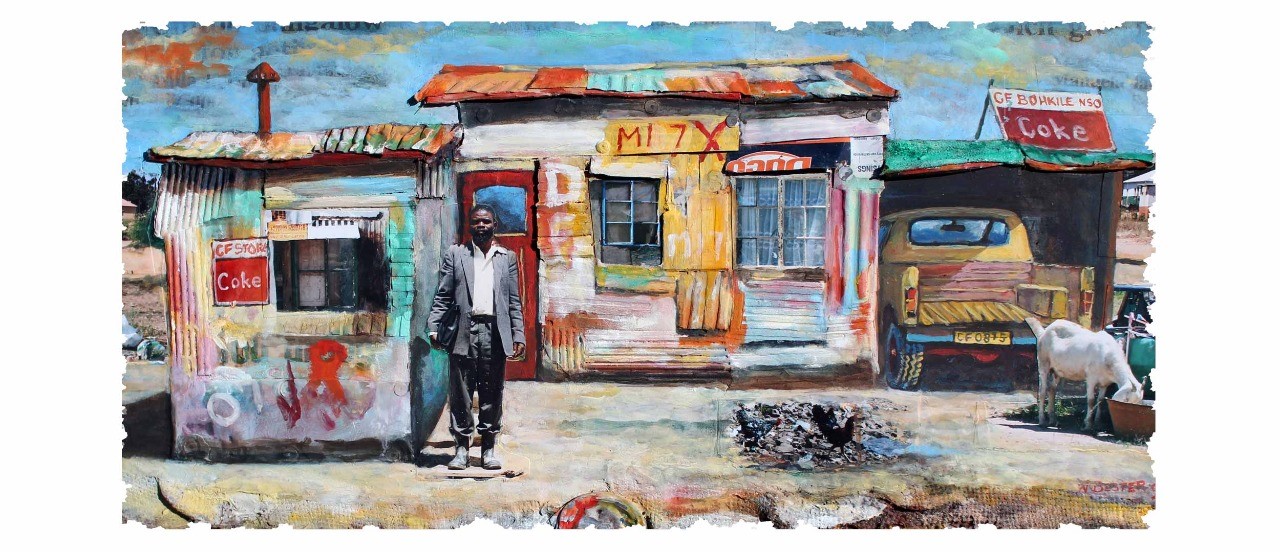

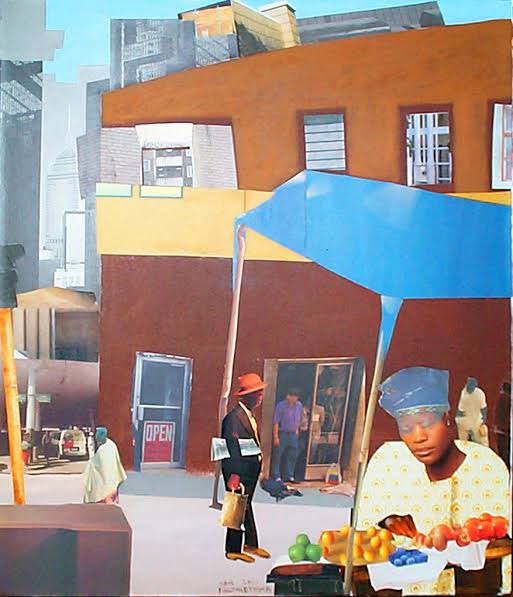

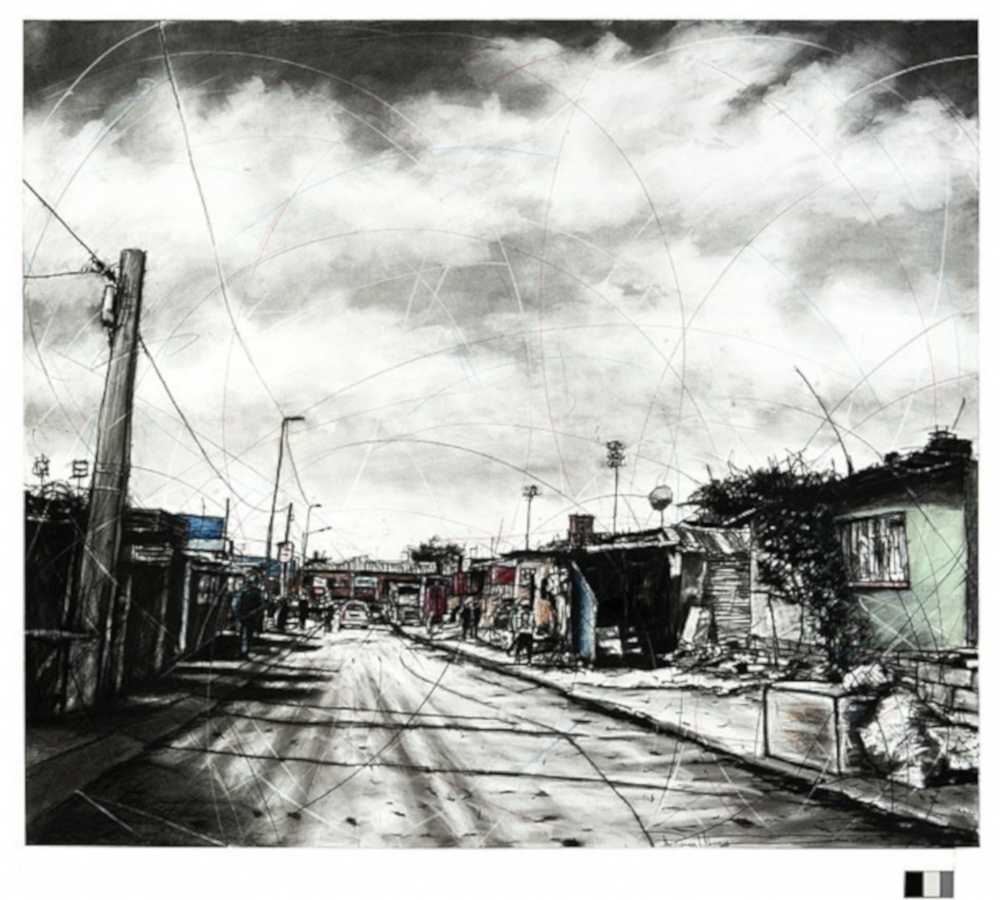

Three decades later the horror expressed by Imbizo seems to have become a reality. Both the sublime and the literal interpretations of the song are characteristic of our present South Africa. Black people still do not own the land and the economy, the same white minority that controlled the economy through exploitation of black labour is still in charge. As Athi Joja puts it, the “post-apartheid era” is a borrowed site where black people exist as just tenants. And this is what Phuzekhemisi meant when he said, Ningabon’ sphila kulomhlaba siyaw’khokhela. We do not only have to pay with money and labour to be on our land but we also have to pay with our lives. The precariousness of black life and landlessness is inextricably linked. Think of the deaths in the townships, farm killings, poverty, Marikana, all these things have a strong correlation with our relationship with space.

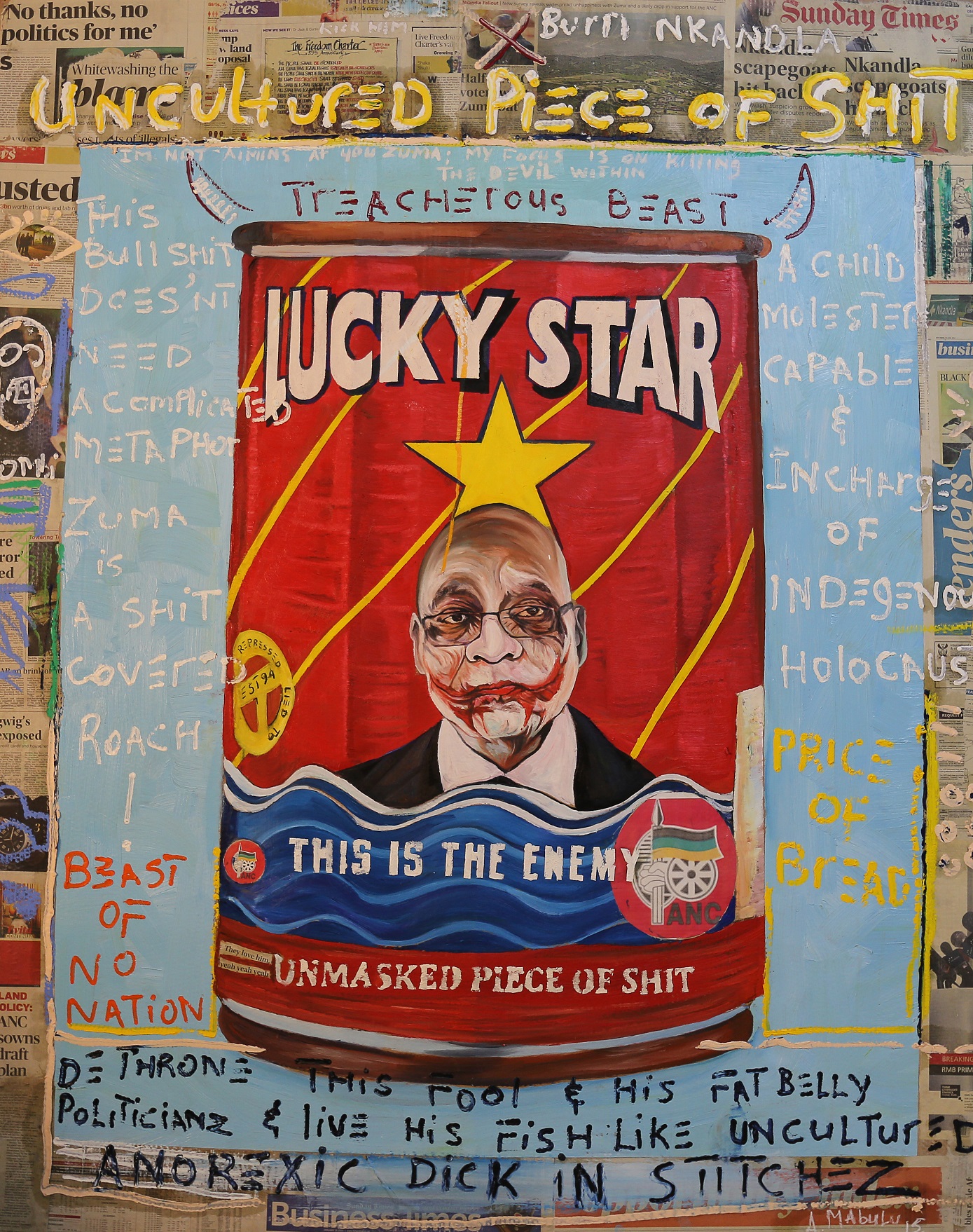

Imbizo noted how the conditions that we are in, our condemnation would also be sustained by a black government which would be comfortable with maintaining the status quo as long they get to live comfortably with their families. Black leaders have proven to be very effective in running the affairs of white people and protecting their interests. Otherwise how would one explain the fact that economic and social hierarchies that existed during colonialism and apartheid have not been altered almost three decades after the ‘end’ of apartheid? How does one explain the rampant corruption by those who are supposed to serve the interests of the people? How have they not alleviated people out of poverty and suffering when they are the ones who make legislation and draft policy? It would not be farfetched to assume that what matters to them is self-enrichment and opulence at the expense of those who they are meant to serve. As Phuz’ekhemisi prophesied what promised to be better tomorrow for all black South Africans has turned out to be a nightmare for the poor majority.

Had we listened closely to Phuzekhemisi we could have anticipated our condemnation in this hole called South Africa. Through Imbizo Phuzekhemisi was able to express what was to become of our ‘post’-apartheid South Africa. This demonstrates the importance of listening to our songs beyond entertainment because they serve a much more important social function than that. We could very well be trapped in this labyrinth of suffering but maybe through our music we can find ways of living better within it. Black music allows us to see beyond obscurities and it is important for us to be intentional and critical when listening to our songs.

*Listen to the song below: