You would recall that in one of my recent essays I made the point that one of the reasons for my focus on the stories of obscure or invisible Black subjects (particularly Black women)-is because I have this deep fear that such subjects will be forgotten and eventually be permanently erased from our memory, with no possibility of retrieval.

Remembering is an essential part of human existence. Not only does it enable human beings to have a sense of historical memory, but it also presents them with the possibility of developing a sense of self-worth and the necessary perspectives with which to meaningfully navigate through space and time, on their own terms.

One of the Black stories that remains an inseparable part of my historical memory is that of our Sister, Maki Skhosana. This is a story I tell as many times as possible with the hope that, in time, it will constitute an essential part of our historical memory as a Race.

I can't believe that last week marked 34 years since the callous and public murder of our Sister, Maki. The year was 1985, the date was the 20th July. It was my ninth birthday and the president of the time was the illegitimate-european-land thief and invader, P.W. Botha.

I was watching SABC news with my father, as he had made it a habit for us to watch the news or read the City Press (newspaper) together. On that day, one of the leading stories in the evening news bulletin was that of a young Black woman, who was being violently kicked, punched and physically brutalised.

All this happened in broad daylight and in the presence of hundreds, if not thousands of people. Later, she was set alight, while a crowd was singing, shouting and watching her burn to death. These horrific images captivated me for a moment but eventually faded from my nine-year-old memory (at least I thought so).

Then much later, when I was a bit older and perhaps more curious, I learned that these horrific scenes where from a funeral and the name of the woman was Maki Sikhosana from Duduza. She was a COSAS (Congress of South African Students) activist who was falsely accused by her own comrades of being impimpi and causing the death of several COSAS activists, days earlier.

It was later established by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that she was falsely accused and that Joe Mamasela (the actual impimpi) and co, with the help of the security apparatus of the Botha regime had orchestrated both the murders of these COSAS activists and engineered the false accusations against Maki.

They had apparently infiltrated COSAS and enticed some of its members with the opportunity of military training. As part of this ploy, they arranged for the delivery of guns and ammunition to a select number of COSAS members. These guns and ammunition were apparently booby-trapped and when they were delivered to the select COSAS group; they exploded and killed them brutally, as they were inspecting them.

At the TRC, Mamasela testified that they had engineered all this and pinned in on Maki as a tactic to sow conflict within COSAS and further the racist-minority-settler-regime's broader strategy of getting Blacks in South AfriKKKa to kill each other.

During her testimony at the TRC, Maki's sister, Evelina Moloko, had this to say about the circumstances around her sister's murder:

“There were certain rumours that they wanted to kill Maki...because she caused the death of certain youths who died due to being blown up by hand grenades. Now, those youths who were allegedly killed by hand grenades were three, and the whole three died next to my place... Now, when the hand grenades exploded we were all asleep and Maki was in the house also asleep … We were scared, we did not even look through the window because we thought whoever was shooting outside would also shoot at us if we peeped through the windows or we opened the doors. We ended up not knowing what had happened until the following morning at five. It seemed that it was common knowledge that Maki had a hand in the killing of those youths. I told (her) it was better for her to run away and she told me she was not going to run away because whatever they said she had done, she had not done, she was innocent. It was very hot and I made fire when I got home. Just when I was taking the ashes into the dustbin, three girls went past my place. They were shouting slogans and they were saying that they had burnt Maki. When you look at your sister’s body, you feel it in your own body. I approached her from the feet but I could not see her face because there was a large rock on her face as well as her chest. I discovered that all her teeth were missing. She had a huge gap on her head, she was also injured and she was actually scorched by fire. Her legs were taken apart, broken glass had been shoved into the young woman’s vagina.”

Like that of so many Black women across the world, Maki's death was so brutal and no amount of words can aptly articulate the depth of the brutality that was unleashed on her body. And even though she was an activist in her own right, she is one of the many Black women whose stories don't feature prominently (if at all), in what is commonly referred to as the liberation struggle narrative.

This is largely because of the deeply patriarchal nature of what is called liberation movements and society in general. But there is also another reason why her story doesn't feature prominently. I strongly believe if her death is to be properly investigated, it might implicate a number of people (some still alive), both from the side of the securocrats of the apartheid state and those who formed part of what is called the liberation movement.

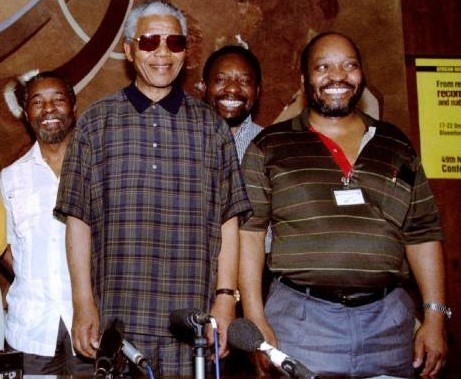

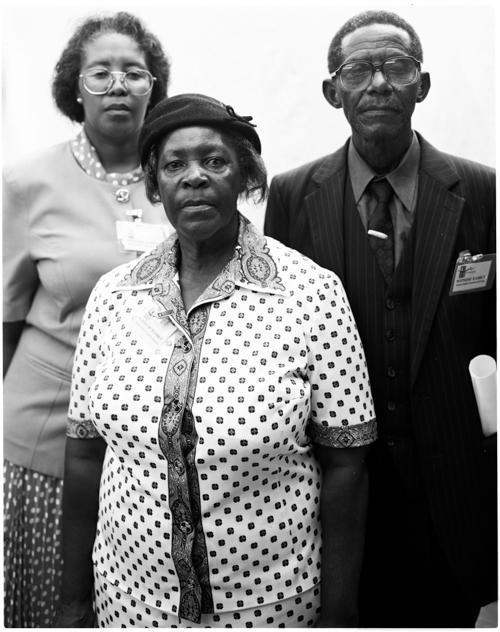

Evelina Puleng Moloko, Diane Moshapalo and Reverend Moshapalo, family of Maki Skhosana, a twenty-four year-old female ANC activist who was burned to death in the first officially acknowledged 'necklacing' incident in South Africa. Duduza, 1997.

Maki's brutal killing also reminds us how the multiple dimensions of Black pain and suffering converge on the body of the Black woman. Furthermore, the recent high court judgement on the Ahmed Timol murder should encourage all the families of those Blacks who were killed by the apartheid regime, to pursue justice.

Forgetting, just like remembering is a process that usually happens naturally, but we also know from lived experience that, forgetting can also be engineered. This is particularly true for us as a Race. We as Black people are constantly pressurised by other races or their stuur-boys and stuur-girls among us, to forget important parts of our history.

In the context of a world that is defined by racism/white supremacy, patriarchy, misogynoir, capitalism, neoliberalism and anti-blackness- it favours the oppressors when the oppressed slavishly accept a situation wherein their oppressors do not just seek to erase their memories, but also dictate to them which parts of their historical memory they may retrieve.

Just as there are consequences for being remembered, there are also consequences for being forgotten. For to be forgotten is not just to cease to exist in memory, but also means to be physically invisible even when you're physically present. Globally, invisibility and absence are features of Black existence, which is actually nonexistence.

By choosing not to remember Maki, we are not just adding to the physical brutality that was unleashed on her Black body, but we are also ensuring that her name remains buried along her battered Black body-deep down in the belly of our troubled land.

Our story as a Race is written on the body of Maki and each of her scars represent the many contours of Black pain and suffering. Through our cowardice (which we have learned to justify through smart phraseology), we as Blacks in South AfriKKKa have willingly become part of a nauseating conspiracy of silence on Black pain and suffering (something which is now a global multibillion dollar industry).

We form part of this conspiracy because we are terribly afraid to offend those among us, who have auctioned their souls to become the glorified stuur-boys and stuur-girls of our Race-enemies. We in the Black world must never forget our Sister, Maki Sikhosana.

Camagu!