Our languages get lost in translation. And because we have been so fixated and obsessed with mastering our colonizer’s tongue, we have completely divorced ourselves from the beauty and philosophical paradigms of our native tongues.

It is my assertion that our languages, in their uncorrupted states, hold the keys to what and who we truly are. Embedded in our languages are codes and metaphysical wisdoms that are a many century old.

Earlier today, while browsing through books at a local book stall, I overheard a conversation – between an elderly man who had just purchased a Setswana novel and the owner of the stall. The conversation revolved around the Setswana language and its many intricacies. My interest peaked when they discussed the term “mokapelo”, which is a term that is generally understood to mean “lover” – or “the one who owns my heart” – or “the one who has captured my heart; my partner”. It is a common term used by those who are involved romantically. The stall owner suggested that the popular phrase is actually a corruption of the original term, which was “mooka pelo” – which holds a much deeper and more profound meaning altogether. “Go oka” means to heal. “Mooka” or “mooki” is the one who heals. “Mooka pelo” would therefore translate to “the one who heals my heart’’.

Who knew that one “o” could mean such a key difference in the layers of meaning! Love shifts from being something merely possessive and demanding (like owning and capturing someone’s heart) and transcends into being a process of healing. Most of us are crippled by demons and insecurities that we are constantly trying to fight. As a conquered people, these demons are quadrupled by factors such as poverty, landlessness, childhood traumas and coming from broken families, to name but a few. Our hearts are burdened and broken in ways we cannot even begin to comprehend. Now imagine this – imagine meeting someone, who by virtue of being themselves, heals that which is broken inside you... Mooka pelo!

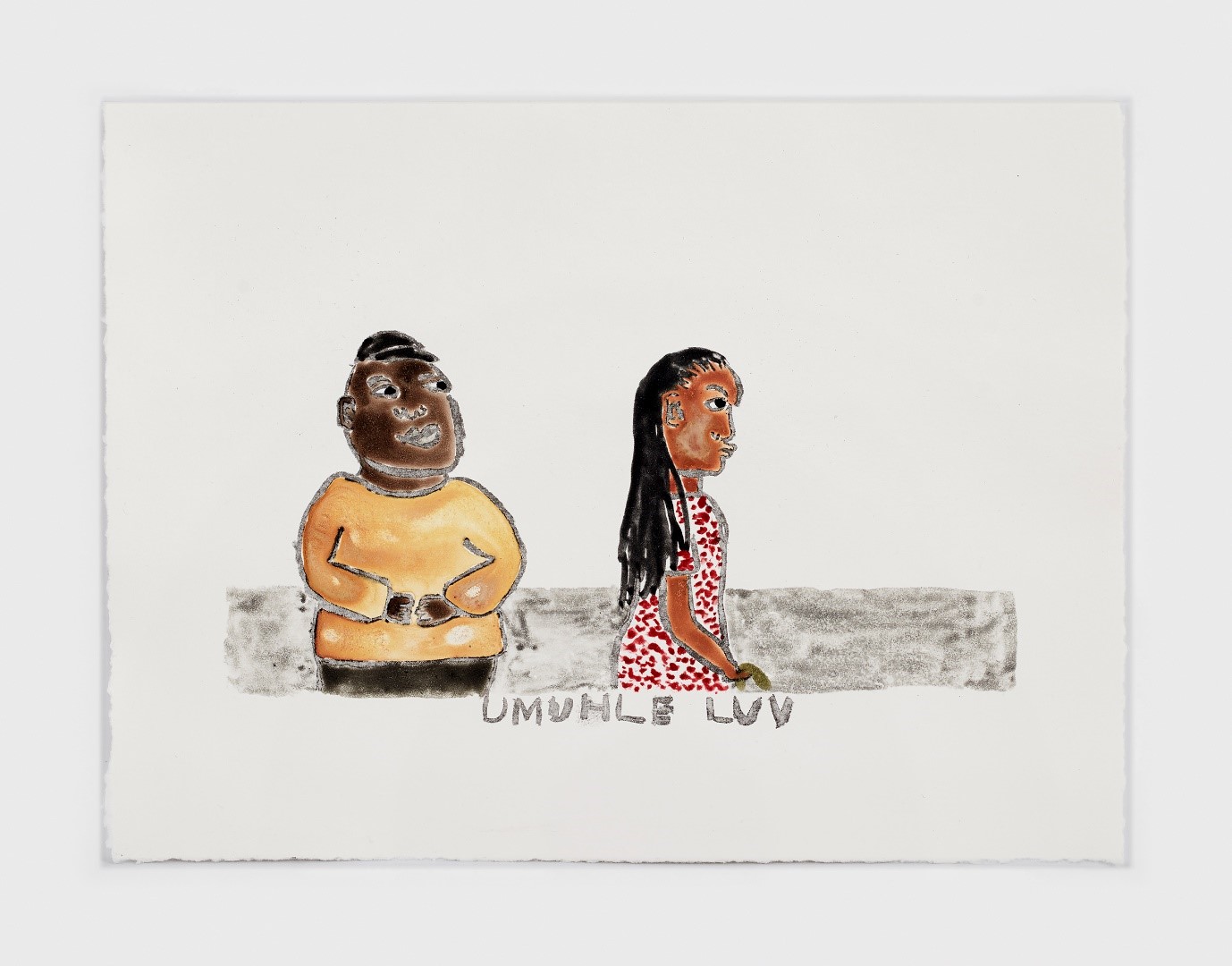

Now we find ourselves in relationships or striving for relationships with people who “drive us crazy”, we speak of “falling” in love and of having a “crush” on someone. Our words bond us to our reality, and the language we use to define what we allege to be love is very violent and low-vibrational. Being in a relationship with someone who drives you “crazy” is surely an application to unpleasant afflictions? Should we rather not strive to “rise” in love, as opposed to falling? And crushes, when given the opportunity, really do live up to their names, do they not? They crush! We affectionately refer to people we are intimate with as “motho waka” or “muntu wami” (my person) – perhaps some forms of domestic violence arise from these misconstrued perceptions that one person is the owner of another in a relationship. But I digress...

Today, people say things like “mjolo wanyisa”, and this could be attributed to the painful mismatches people find themselves in. Today, it seems to me that relationships are primarily motivated by extrinsic factors – extrinsic motivation involves gaining rewards that are not inherent to the relationship – that is, gaining something else because of the relationship. For example, the relationship might give us access to certain services, goods, money, information, and status. Dating a celebrity may help access money and status. Dating someone popular may help access a new network of friends” (pink families, 2014).

In essence, the relationship becomes a vehicle to something else – a means to an end. People find themselves in relationships not because they derive comfort, satisfaction and feelings of love and healing from the relationship, but because the relationships are stepping stones. Many people fail to free themselves from toxic relationships because they are tightly bound by all these other external factors. In such situations, love ceases to heal – it begins to physically, spiritually and emotionally incapacitate. Psychologists are making a killing, trying to diagnose and treat the ill-conceived mismatches of many wretched souls.

Our languages, in their undiluted form, are meant to guide us. We are generally a people with a strong oral tradition; the spoken word has always held pride of place in our culture. We resonate richly with stories as well as narratives rendered through song and dance. Our languages are emphatic and effortlessly poetic. I recently learnt that the word “Nkulunkulu” (a word now known to mean “God”) is another ancient term lost in translation. Apparently, the original term was “o Mkhulu bo Mkhulu” (the grandfathers of our grandfathers) and because of the white man’s failure to mould his tongue and pronounce “o Mkhulu bo Mkhulu” correctly, he birthed “Nkulunkulu”. This version of the etymology is not too far-fetched – most African people can attest to having had, at one point in time, their names and surnames completely butchered by the lazy and disinterested tongues of our white compatriots. Now, if this is indeed true, the implications of this seemingly minuscule mistake are quite devastating.

Jennifer Weir (2005), postulates that Christian missionaries, while trying to understand the psycho-spiritual dynamics of the African (or the lack thereof) and their understanding of Creation and the hereafter – superimposed Christian ideals of a “supreme being” on African spirituality. In a paper titled “Whose nkulunkulu?”, she laments: “The interpretation or invention of uNkulunkulu as “God” is an example of white systems of understanding being grafted onto African systems that are not necessarily compatible, and it has undermined the importance of ancestors in Zulu religion and their role in the ideology of the Zulu state”. Simply put, it means that spiritually, we are lost at sea – a wandering bark with no compass to direct us to the true north. Or worse, with a broken compass – with a false north. And we are sailing towards nothingness full-steam ahead. Given these grave historical-linguistic misjudgements, and the current lack of enthusiasm around studying our languages as well as their etymology, we will remain lost beyond redemption.

Had we been in tune with ourselves and with the words and expressions used by the grandfathers of our grandfathers, perhaps we could’ve known that the right people for us are those who feel like healing – bo “mooka pelo” – and not those who make us feel “weak” at the knees. Perhaps we would have a better grip on our spirituality and other aspects of our lives – if we did not mistakenly worship a narcissistic, enigmatic figure in the sky, but instead paid homage to the most ancient beings whose DNA gushes through our veins, o Mkhulu bo Mkhulu!