Birthed out of anger and the need to highlight the openly pernicious and subtle forms of violence inflicted upon black women, Lebogang Mogul Mabusela’s work uses humour and vernacular phonetics to drive its point home. Comprising prints, drawings and sculptures, ‘Ukwatile?’ forms part of the artist’s ongoing series, Johannesburg words, which was inspired by Robert Hodgins' 1987 work of a similar title, Jo'burg words, as well as Makoti technologies – a ‘fake’ online bridal gift shop where the artist offers guns and other devices made of paper, lace, biscuits, hair and other materials. The shop has a satirical take on the different ways in which women can protect themselves against patriarchy and other forms of violence. The products on display come with a warning tag: “Our products have a tendency to cause irritation to people who like their women nice. If irritation occurs, plz continue. This gun is more suitable for those people who don’t have a sensitivity to an overload of femininity”.

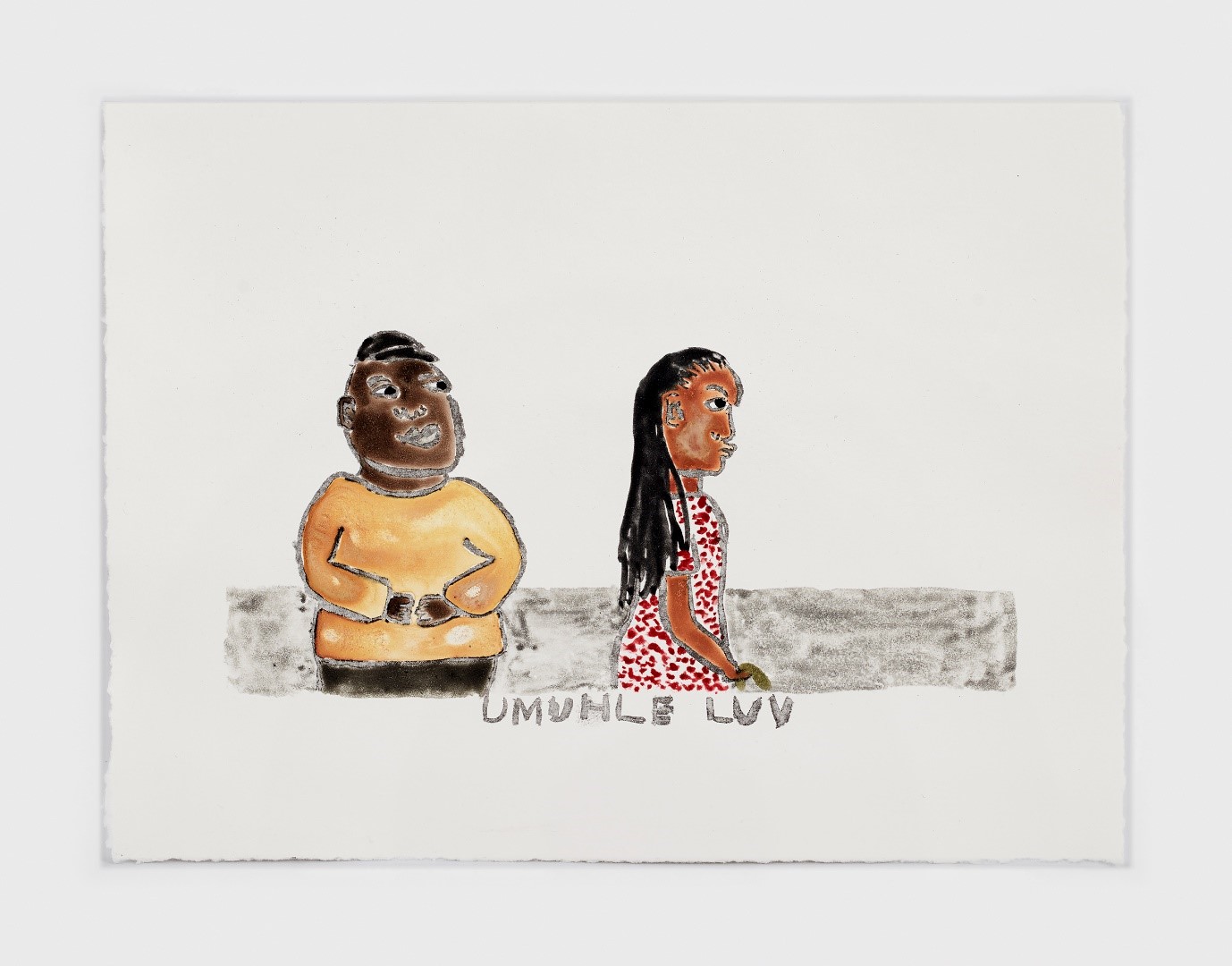

Lebogang’s work has been described as a reflection of how black women navigate misogynoir. With Ukwatile? currently showing at Stevenson, it features oil pastel portraits, storyboard-like prints, glitter as well as paper and lace sculptures. The first series of pictures portrays black men and women in different verbal scenarios/ encounters. There are two subjects on these small storyboard-like prints – the man, making an advance – and the woman, who doesn't seem interested in what the male figure has to say. The male subjects are mostly making comments on the woman's physicality, or are just trying to get her attention by asking things such as – "Uhlalaphi?", "Ushadile?", "Ngikukhape?" or "Ukwatile?"… These words, which can be seen across the artworks, are utilized by the artist as a comical take on catcalling and voyeurism. Early prints foreground the speaker's words like speech bubbles, depicting their shamelessness and open acceptance. More recent portraits have words scrawled at the bottom or featured on gold chains, offering reminders that this form of violence is a timeless fashion; made insidious by how it feigns subtlety.

The second series of artworks are portraits – wherein the male characters are the main characters, with gold teeth and gold chains that spell out words like ‘my size' – Mabusela’s body of work about language, catcalling and voyeurism, subverting the male gaze, interrogating male desire; showing how dangerous it can be. The artist explains that she chose a comic-look approach to reflect on how much of this is not taken seriously. Beyond the mockery, the jest, her levity critiques a society which limits its understanding of the experience of Black womanhood to one of struggle and lamentation, devoid of joy and laughter.

Mabusela asserts, “I decided to keep [the oil pastel portraits] backwards like a mirror because another thing I grapple with is that for us – people who go through this – we understand what’s happening. We can laugh because we understand the seriousness. But do they see that I’m critiquing them? Are they just also going to laugh and walk past it? The mirroring gesture calls for that introspection”. The light-hearted approach is intended to highlight how issues pertaining to black women are generally not taken seriously. The theme is the same throughout all the pieces: the fraught relations between male and female subjects. Even in the mirror portraits, where it is only the male in the picture, the audience becomes the female subject to which the words are directed – and in the case of a male audience, the portraits become a sort of mirror where some degree of introspection is encouraged.

At first glance, Lebogang’s work gives one comedic relief. It is amusing to see the representation of these words, which are part of the everyday lived experience of most black women who reside or have the experience of being in a kasi setting. This is mainly because of the language employed. There is a moment of realisation that settles when it dawns upon us that this lexicon – these phrases – are quite commonly used. Most black South African women have heard these phrases hurled out at us at one point or the other.

So, one begins to ponder – were all these men whom we pass on the streets birthed by the same mother? Is there a secret meeting place where they collectively decide on these ineffective ‘mating mantras'? The irony is evident in the familiarity of these phrases, and it is almost impossible to truly garner an appreciation of the work without this unspoken affinity with kasi life and South African vernacular. Upon deep reflection on these pieces one can speculate that the artist is well-versed in the Black-South-African-woman experience, as such artistic precision can only be eked out by a soul that has survived from a setting that was not designed for its survival.

At the core of Mabusela's work, how we relate to one another is being zoomed in on. How we see each other and ourselves, and how we think others see us. And even how, on a deeper level, subconscious feelings of being unsafe, vulnerable and exposed marinate below the surface of these works. A world where women cannot bask in their femininity and ‘niceness' – an unbalanced world where the need for “protection” automatically points to the precarity of being female… about the target market for the cutlery collection sold at Makoti technologies. What state of psychological terror and despair would drive one to the point of finding whatever material there is, in this case: paper, lace and glitter, and assembling them as a symbol of defiance against a world that seems impervious to the pain of black women?

An unnatural setting invariably produces unnatural inhabitants, although living through the contrast forces us to normalise the abnormal – and such works remind us that there is indeed something in the water.

Info:

Stevenson

JOHANNESBURG

Until 20 August 2022

STAGE

LEBOGANG MOGUL MABUSELA