As we have just concluded women’s month, it is clear that black women are caught in a conundrum. They are in a constant war for visibility and, simultaneously, against hyper-visibility. For a long time, women have not been recognized as beings capable of making any positive contribution in wider society; their role was almost always limited to the domestic. Not long ago there were hardly any black women in fields such as science, architecture or even politics. One could argue that this has changed over the years, but has it really? There is no doubt there has been an upsurge of feminist activity, and it has been liberating and exciting to say the least. The fact that women have been speaking against their marginal position in society signals a move towards a progressive direction. However, the reality of the matter is that conversations around the need for women to be at the forefront have not necessarily translated into any material change. This is to say, outside of theoretical ramblings and manufactured solidarity with women, there has not been significant change when it comes to gender disparities.

There are many reasons for this. For one, the logic of patriarchy tells us it is unimaginable that black women are also able to do what men can do, let alone perform better than men. It is because of this neurosis that hypervisibility kicks in. Where there is an impulse by society to scrutinize women, to suspect them and have preconceived ideas about them, often negative ideas will proliferate. So even when women do occupy positions which were an exclusive preserve of men, the problem still persists. Women are used/viewed as tokens, subjected to impossible conditions where they are reduced to only sexual beings, and this is evident in the high incidence of sexual violence against women in places of employment.

There is an urgent need for society to change its attitude towards women. There is a need for society to understand that there has been a systematic erasure of women and their voices. It is this erasure that sustains patriarchy and all its manifestations. However, all of this is not going to happen through wishful thinking. The system of patriarchy and those who maintain it must be called out. This part is very important because there are actual people who deliberately create conditions that undermine women and all they have strived and fought for over the years. The continuation of women’s oppression has architects and enablers, and to dismantle and resist it, those people have to be challenged. We have to challenge years of viewing women as disposable objects; objects that are always already available as supplements and accessories. If these things do not change, black women will, as John Stuart Mills might suggest, always be unacknowledged outsiders.

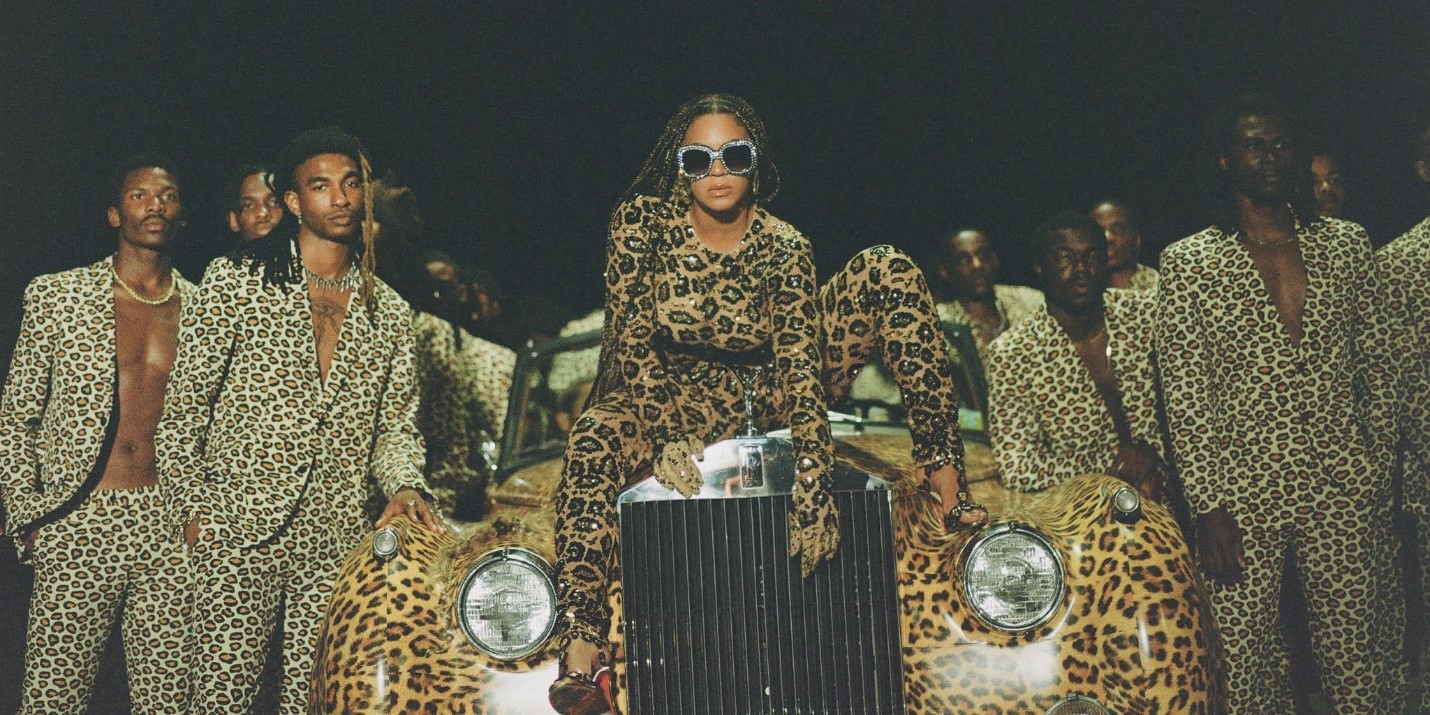

Luda Nochlin asks a very interesting question; why have there been no great women? I am interested in thinking around this question from the vantage point of black women. From the perspective of marked women, for whom and about whom the colour of their skin speaks even before they open their mouths. Black women; ‘overdetermined from without’. There have not been great black women because society, since time immemorial, has always scorned, misnamed and stifled women. There have not been any great women because institutions that have the responsibility of being the custodians of our history have been complicit in denying women their rightful place. In museums, the majority of history recorded is the history of men. It is the history of how men have helped shape the world, what they have invented; it is the history of wars fought by men and the victories of men. Now this is not because women were sleeping throughout time; they were there but there is a deliberate choice not to see them.

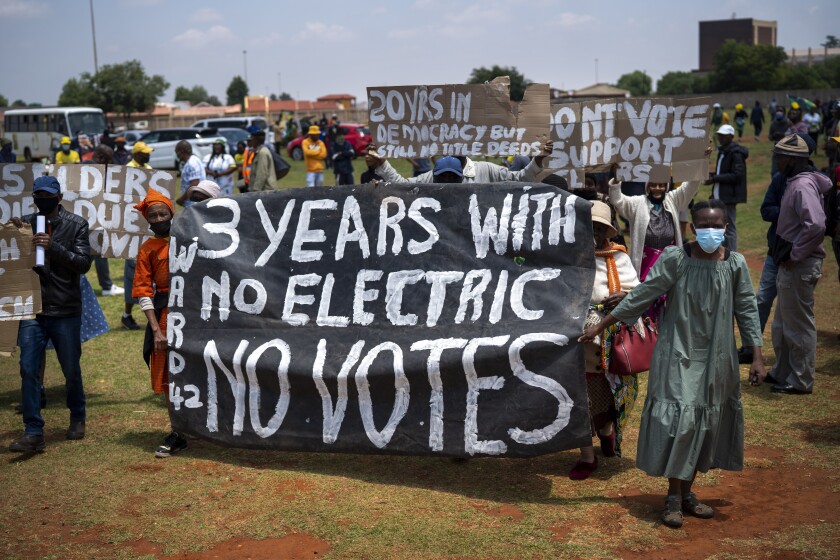

If one thinks about public space in South Africa as a site of remembering, you will find that most monuments are in honour of men. There are hardly any statues or sites that invoke the memory of women who played a notable role in our society. This is perverse, so much so that we would rather have debates about whether or not we should keep statues of racists and colonizers; instead of thinking about the silences in our past. Instead of thinking about those who have been denied visibility. During the debates around the destruction of monuments that trigger our painful past, there were hardly any conversations around the kind of history we want to remember. The urge to insert women into history was not strong enough, and whenever this was raised it was ignored. This is why most sites still have names and statues of your Mandelas, Sobukwes, Tambos, Sisulus and Hanis; and none of the many women who laid down their lives for a liberated South Africa.

One might see this as something that is perhaps unimportant, or that does not deserve critical attention; but the reality is that the spaces we inhabit have a lot to say about where we are as a society. The fact that there are few women in the boardrooms speaks volumes. The fact that when we think about the project of renaming streets and places it is always men that are thought of signals a problem. The reality is that in art galleries there are fewer women exhibitions. This tells us how, despite the rhetoric around gender equity, women still find themselves without a place in this country. Even when women prove beyond doubt, as in the case of Bafana Bafana vis-à-vis Banyana Banyana, there is little recognition and appreciation of this. What do we make of this? How do we move from token equality to true equality that is reflected in our public spaces, in architecture, in sports and in all other spheres where women find themselves excluded, still?