"They never told us why they arrested him. Even today I want to know why they arrested him - what did he do - because I don’t understand why did they arrest him? I really don’t know and I want to know? Even today, its years and years but I don’t understand why did they arrest him and I want to know why did they arrest him? I want to know the reason why? Because I cannot wake him in the grave and ask him Phaki what did you do why were you arrested? Because I don’t know him as a criminal - I know him as a child a good child who was listening to his parents - I don’t know I can’t even say..."

These were the painful and answer- seeking words of Phakamile Mabija's sister during her testimony at the toothless Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings in June,1996, in Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe

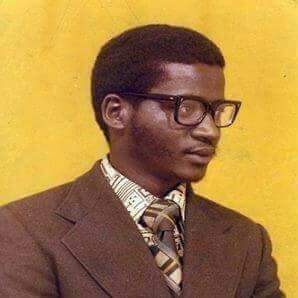

Today marks the 42nd anniversary of the brutal murder of Phakamile Harry Mabija. Born in 1950 in Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe, Mabija was a teacher at Zingisa Primary and dedicated a community activist.

Through his community activism, he involved young people in the township of Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe in a variety of personal and community development projects.

Consequently, a great number of some of today's prominent Galeshewean's attribute their achievements to his influence on their lives. He was also a member of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

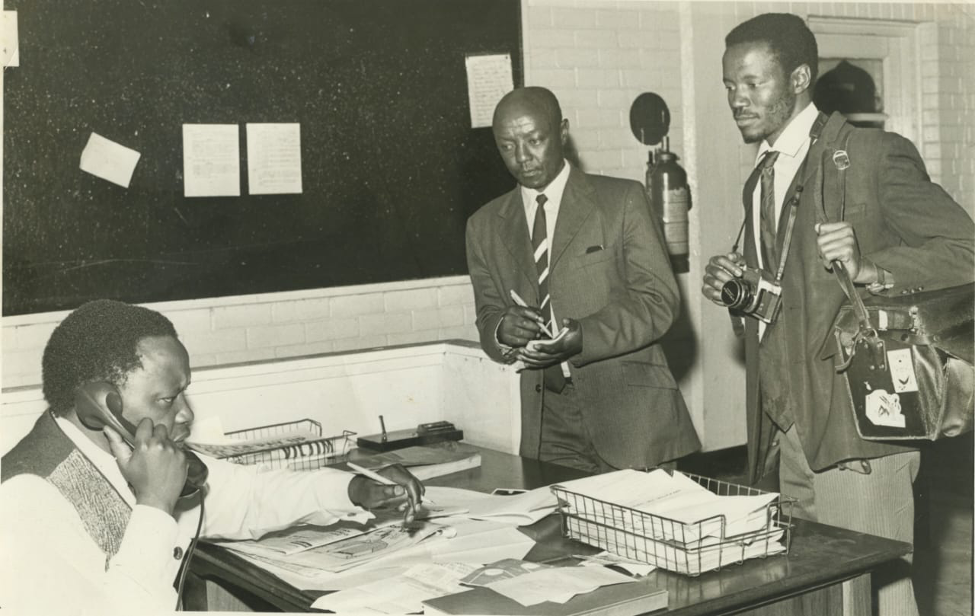

The agents of the apartheid government accused him of being the instigator of the Galeshewe Bus boycott and detained him under the repugnant Riotous Assemblies Act. While in police custody, he was murdered in cold blood, on the eve of his trial on the 7 July 1977.

He plunged to his death after being flung through the window of the 7th floor of the notorious Transvaal police station in Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe. Unsurprisingly, the Special Branch story was that, he committed suicide. An official lie that the Apartheid police used to explain most deaths in detention.

The Circumstances of His Murder

Describing what she saw, Henriëtta Manzana, an elderly Black woman who worked as a 'tea lady' (as our mothers who did menial chores for whites, were referred to) at the Transvaal road police station said:

“I saw Phaki coming from upstairs - I first took food to him and Oscar (one of the police men who arrested him) said I must put it down...I had water, he (Mabija) was shaking and said I must put it down he will eat when he comes back...when he came back I saw Phaki went through the window - they never brought him to me...Maynard (the white police captain) they never told me that my sister’s child has come back - we will kill him now - we just saw him flying from on top... when I was sending tea to Maynard...."

She goes on "I didn’t hear anything he just came from the top floor - I didn’t hear him crying - I didn’t see him doing anything - I just dropped the tea and went down to the ground - trying to hold Phaki - but I couldn’t save him because he was already on the ground and he was lying facing down. When I went to him - Mtshisana said hey - and I said that’s my child’s son you can shoot me if you want to."

The Last Day His Family Saw Him Alive

Describing the last day, they saw him alive, his sister said:

“.... two policemen and they got inside the house. So we were all sitting in the house in the lounge. So they came in with Phaki and Phaki was dry and looked terrible as a result of being beaten up by the police. The police lifted up the carpet and after that they went into the bedroom and they searched. I didn’t see them coming out with anything and then after that they went outside with him to the gate. And then as they were going out by the gate they then turned back into the house again and they said him "gaan groet jou mense want jy sal nie vir hulle weer sien nie (go and greet your people because you won't be seeing them again)."

She goes on

“So we were surprised and shocked about this statement but anyway we sat down and talked among ourselves. It was not long afterwards then I just took my cousin half way as she was leaving because she was with us and we just heard while we were on our way that Phakamile is dead. When I heard that it was a horrible thing to hear and it even became difficult for me to hear this and this was the most painful experience and I don’t even know how I got home."

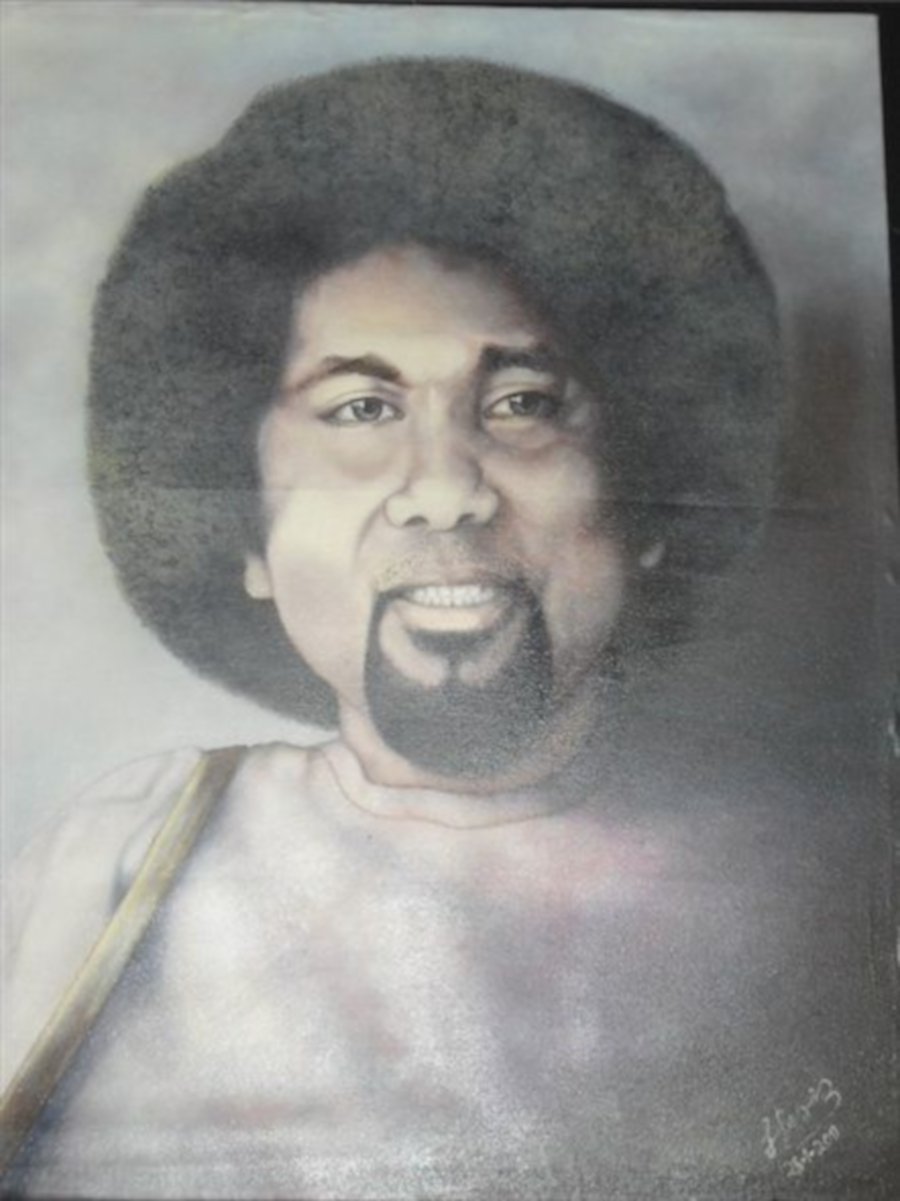

A Beautiful Life

Mabija was such a kind and gentle soul and even this didn't stop the racist-anti-black system from murdering him in cold blood. This irony is perhaps aptly captured in his sister's words who describes him thus:

“Phakamile was a very good child and he hated everything that was wrong. He was a person who was involved with the scouts and church activities and he was involved in everything. He was involved in everything, in all the church activities, at school, sports and he was a person who wanted the best and who was goal orientated and he committed himself in achieving his goals. He was a person who was a visionary who channelled all his energies to accomplish the best of things.

She goes on:

“He wanted success - he wanted the good things to succeed. He would say ‘I want a plan to succeed and when it succeeds it should benefit all’. He always wanted his dreams to come true and be successful. Everything about him was so amazing because he was such a great person. And about the fact that he killed himself - that is not true - there is no such a thing like that.

Final Thoughts

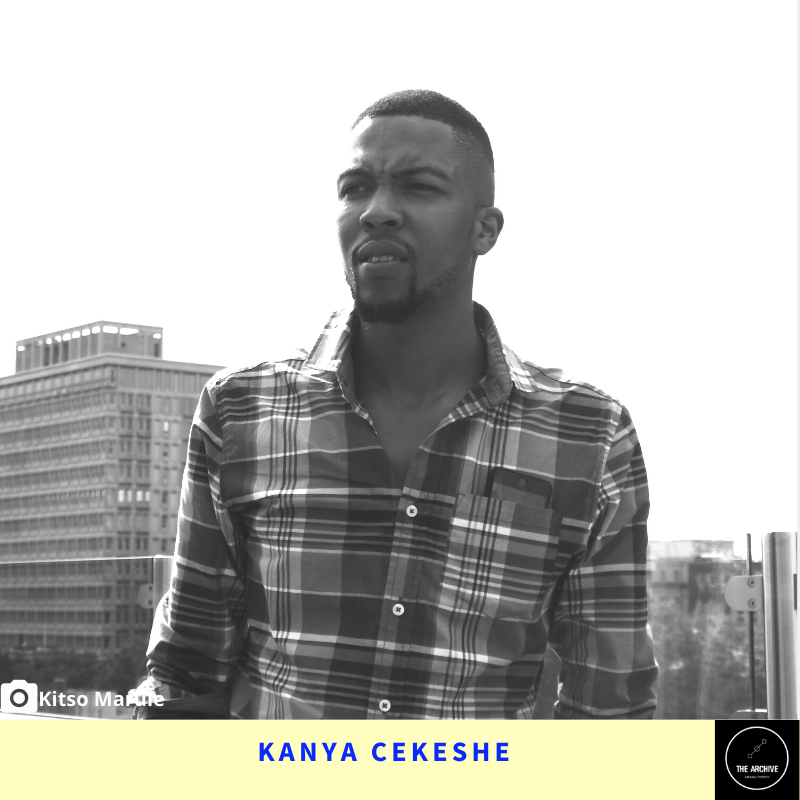

I remember growing up in Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe, how, year-after-year, the Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO), would hold commemorative events in his honour at the Fatima or St. James church.

Those of us who were part of these commemorative events, were always worried whether the generations to come will ever get to know about lendoda yamadoda (a man among men) and all he did for Black people in Ga-Kgosi Galeshewe (especially the youth).

Despite our occasional doubts and meagre resources, we persistently commemorated Mabija, year-after-year, without fail. In the early 90s as AZASM, we campaigned for the local Phatsimang College of Education to be renamed after him.

Then later in 2008, AZAPO's National Chairman, uBab'uZithulele Cindi, led a protest march to the Northern Cape Provincial Legislature. One of AZAPO's demands was that, the police station, where he was murdered (Transvaal Road) and the street wherein its situated, be renamed in his honour.

After some serious head scratching, the provincial government eventually agreed to AZAPO's demand. Then later as part of the state's heritage day project, Transvaal Road was renamed after Phakamile Mabija. However, the police station is yet to be renamed and AZAPO has made a follow up on thi submission. Later, a youth learnership was also named after him.

The tragedy of young Mabija's life is part of the largely unexamined fatal existence of Black people under racist-european-minority rule. It is therefore absolutely critical that my generation consciously digs up these kinds of stories, in all parts of South AfriKKKa, record them and tell them over and over again.

Mabija's story is the story of anybody who regards themselves as Black-not just merely by pigmentation. And if we Blacks don't tell Mabija's story, (somebody else with their own motives), will tell our children and grandchildren this and similar stories.

Just as I have asserted in other political biographies, those responsible for the brutal murder of Phakamile must be found and made to pay. We must stop talking about Mabija and continue to pursue justice for him and his family. Had he been alive, Mabija would have been 69 this year. At the time of his brutal murder, Mabija was only 27.

Camagu Miya!

Gcwanini!

Sbewu!

Salakulandelwa!

Ngoma!

Vezi!

Rheqwa!

Bhinqele!

Hlangeni!

Ngxongxothela!

Ngqangqa!