It is better when it begins with a confession because a confession frees one from guilt. When one confesses there is almost an immediate vindication that is assumed. It does not matter whether the other person accepts it or not, you confess and a boulder is removed from your shoulders. But the refusal to confess invites heaviness, where your eyes do not betray you, but your whole body will. Your face will say all the things that the heart is concealing. The tension will announce itself, so thick and solid that you can run over it. But for me it did not begin with a confession. It began with a decision. A decision to go to Kwa Mai Mai, a place that has, over the years, earned itself a reputation as the source of the best ‘traditional’ medicine in the entire Johannesburg. Whatever ails you has a cure somewhere in the corners and passages akwa Mai Mai. But this place is more than just a medicine market; it is a response to dislocation. A resistance against an erasure of both history and what could become the future.

I impulsively choose to walk down Queen Elizabeth Bridge instead of the Nelson Mandela Bridge. The two bridges are parallel to each other and both lead to the same place, Bree taxi rank. Both bridges are rat-ridden, thug infested and they sit sternly above railway tracks that lead to where everything ends including life itself; the townships. The bridges have become home to the children who have been swallowed by the ever-hungry stomach of the city. The children we call ‘hobos’, ‘abomacala’ who are likely to die like moths, killed by the very same light that attracts them. Maybe there is a metaphor that can be scraped from the naming of these two bridges, maybe there are many other things that are shared by our dear Queen and our beloved Saint Mandela. But, that is not what interests me today; I am interested in telling you about something else.

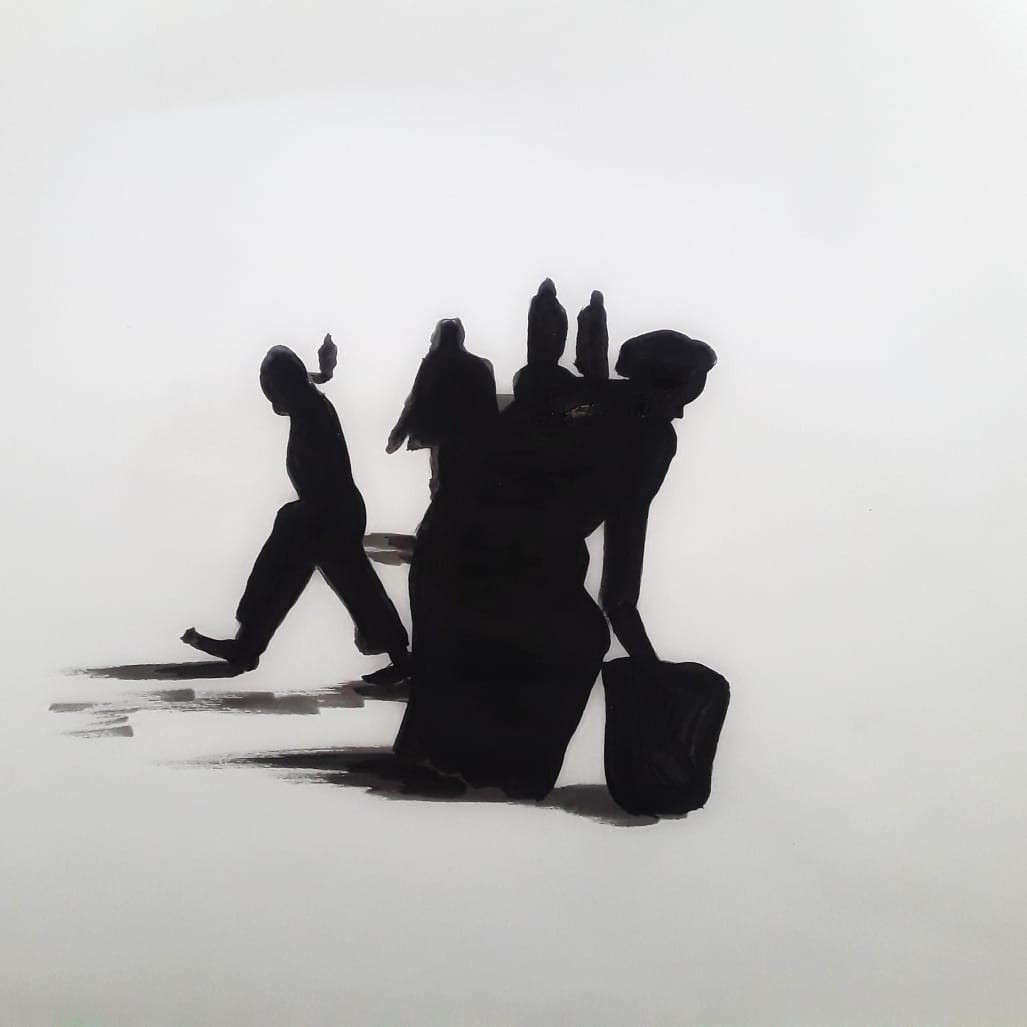

I can already see Bree Taxi Rank; a fluent host of taxis move with hiccups on Carr Street. I navigate through the vendors who shout, stutter and oscillate between Xitsonga and IsiZulu trying to sell me socks. I ignore the rattling sound made by the metal mugs of blind women, carrying children, and humming melancholic tunes asking for donations. The smell of tripe greets me, I pout and look down but the smell insists. Wait, is it tripe, shit or pee? I am unable to discern, maybe it is a combination of all these things. I continue walking purposefully all the while vigilant of anyone who might try to sneak behind me and take my life, the only thing I consider worthy. Besides my defenseless body and tired soul, I only have shriveled up notes of not more than 200 bucks and my burner cellphone to offer.

Get to Bree Taxi Rank, enter a red taxi and sit at the front. Yes, the front seat with all the stereotypes; I count the money. No, there is no drama; no one threatens anyone. Get off at the wrong intersection; it’s my fault, not the taxi driver’s fault. Walk down Albertina Sisulu then Commissioner Street. Whispers of gentrification become louder. The curated graffiti on the walls is clearly commissioned. The pretentious echo friendly benches stare at me as if saying ‘no you can’t sit here’. Security guards are on the lookout for suspicious looking people, most likely blacks. Of course the dreadlocked artists are there selling paintings of giraffes with an orange African sun in the background. I avoid eye contact with the do-good blacks sitting on skinny chairs with their tall glasses of champagne, laughing like they don’t owe their Polo Vivo’s. And oh how could I have missed the outdoor photoboothesque letters hanging from between two buildings written M-A-B-O-N-E-N-G?

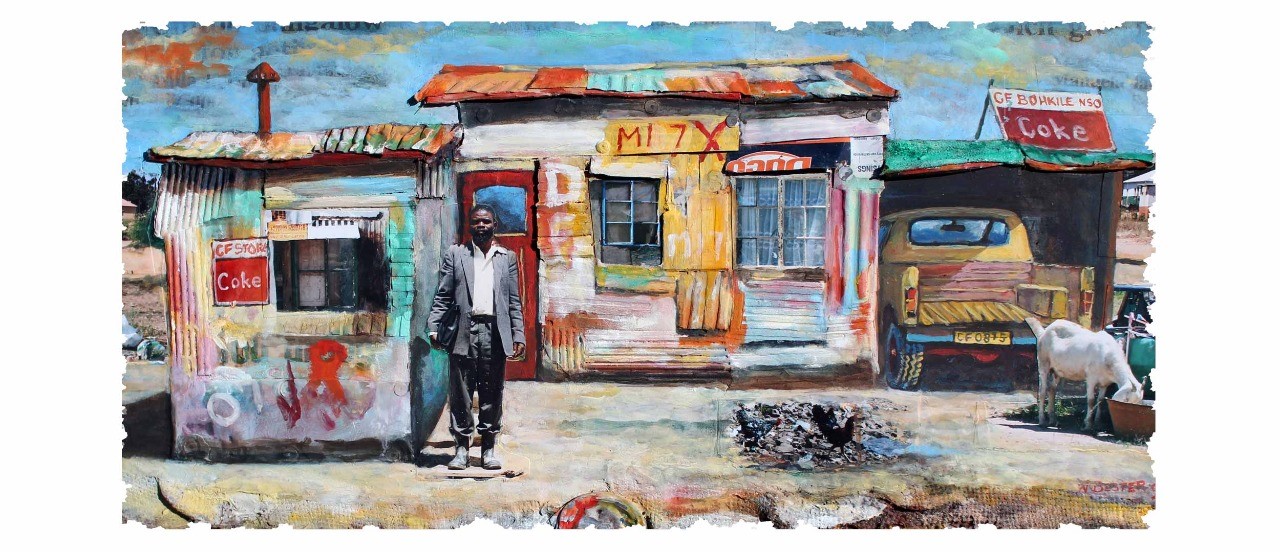

Walk down Fox Street, jump two other streets and I am back to the real world. My breathing assumes its normal rate. Taxis are hooting, I enter a Somalian shop and buy a cigarette, next to it a Nigerian barber sucks his teeth and calls me in for a haircut. I ignore him and continue walking. I turn a few corners and a big sign with the words Kwa Mai Mai eventually appears. I adjust my walk and summon my strongest Zulu accent; it has been a while since I visited this place. It was before university convinced me that perhaps I must loosen my palatal clicks. The mannerism also changed, they had to compliment the new accent. The place seems as if it has not changed but I have become suspicious of everything, even my memory.

Topless men with pants folded up to their knees move up and down with buckets full of water. The car wash is a booming business Kwa Mai Mai, fleets of taxis park there waiting to transport people all around the country. ‘Shisa Inyama lapho wemfazi’ a man in baggy Brentwood Pants, a golf t-shirt and a match stick hanging from his mouth shouts. Our eyes meet and I immediately look away. He recognizes that I am not ‘one of them’; he stares at me for a while. Maybe it is the skinny jeans, the cap, my wondering eyes or it could just be my insecurities getting the better of me. I get inside the gate, the smoke and smell from the braai meat follows me.

It does not take me long to find Mkhize’s house among the rows of matchbox houses that all look similar. I used to come Kwa Mai Mai with my father, he has friends here and whenever he went to visit them he would always take me with him. Yes, he is Zulu and owns a couple of taxis and wives in Johannesburg and KZN. At that point I was too naive to care what the visits were about. Maybe they were casual or they were for a get-richer-quicker potion, who knows? Either way I would just always be excited because after every visit we would have some meat and watch Zulu dancers who performed so much that they caused little tremors around the city, especially when there were white tourists watching.

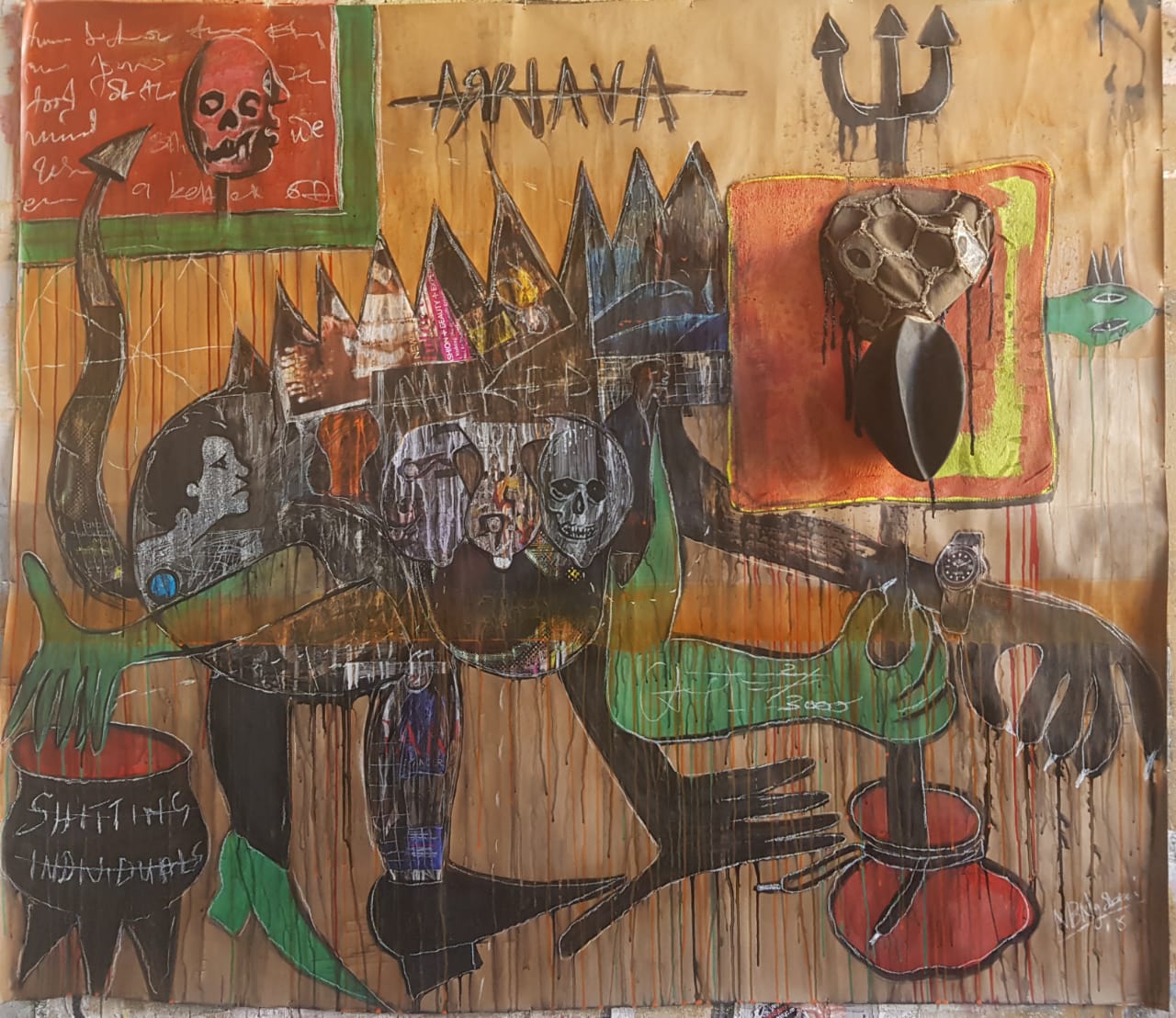

Kwa Mai Mai is one of the oldest traditional medicine markets in Johannesburg, not only that but it is also the go-to area for traditional attire, musical instruments and lightning. Yes, if you search closely within the crevices of the market ‘you can find someone who can sell you lightning to strike someone, for R2’. My dad would always say with a reluctant smirk on his face. The origins of Kwa Mai Mai still remain a mystery even today. Some say it was once a horse stable and when the hostels couldn’t contain the influx of migrant labourers it was turned into a residential camp for workers. Other people claim that Zulu people who did not want to work in the mines used it as a hideout while they operated their own businesses.

When I later talk to Bab’Mkhize who is a second generation resident of Kwa Mai Mai he also seems unsure of the origins of the place ‘we have been here for a long time my boy’ he dismissively responds when I ask him the question. It is easy to believe that it was a stable because when I ask him why it is sometimes called Emahhashini, Mkhize says ‘when white people tried to move us with their guns they couldn’t because they saw a thousand warriors carrying spears all riding white horses. They left their guns and fled, even today you will never see a government here. We don’t pay any rent, any electricity to anyone’.

Kwa Mai Mai is a neatly compact village with paved alleys. The houses are similar and next to each other. You differentiate them with the numbers on the burgundy wooden doors or with the goods they sell which usually hang outside their small verandas. If it is a Sangoma’s house you can easily identify it with a dried monkey or dead snake hanging on the veranda. If indlu ye Nyanga you are likely to see dry aloes and herbs neatly arranged outside the house. Other houses have drums, traditional attire and for the first time I notice that the coffin manufacturing business is also becoming very popular. Mkhize is in 223, beneath the house number the words Kwa Mkhize are written with turquoise paint on the door. I knock and wait for a while before knocking again. A tall man opens the door, I look up and it is Mkhize. There is no way of missing him; the shade of his skin is so dark he might as well just use black polish as a moisturizer and the texture is so smooth his face glistens, leather. He looks at me and smiles immediately. ‘Mfana ka Mbhele’.

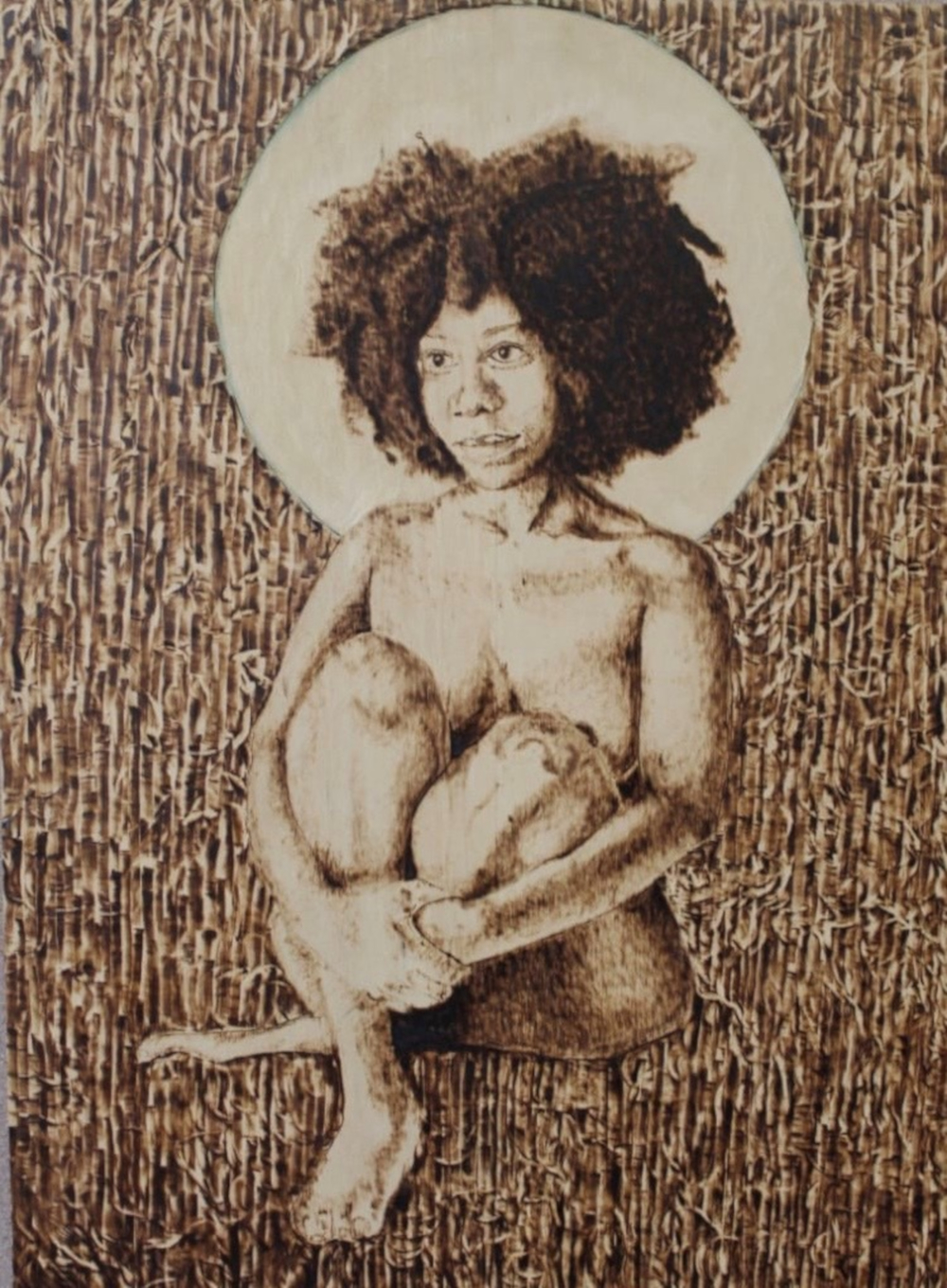

Inside the house there are jars with dried leaves and herbs everywhere, a cowhide rug covers the floor and a light smell of impepho lingers in the room. We do small talk, he asks me whether I still dance, when last I went home and then the elephant in the room. What brings me to see him after such a long time? ‘Is everything fine, what ails you my son? You know I can help you,’ he says while staring at me directly. I fiddle with my thumbs; phlegm stops my words right in the middle of my throat. I clear it and then respond ‘I am here to consult’. I should have spoken the truth, I should have just confessed and told him that I am here to gather information so that I write about you. So that I write about how interesting YOU people are. But I am not brave enough, I do not want him to think I have become one of the white-blacks who speak English from the nasal. I wanted to maintain my long gone sanctity as one of their own, knowing very well that I no longer am.

We go inside another room in the house, I leave my shoes at the door and he points to where I should sit. The room is dark; the only light is from a candle that sits across me in the shrine. Silence is heavy and I can hear my heart beating, regret is already settling in. Perhaps I took this a little bit too far. He burns incense next to the candle, blows it then comes near me with a small leather bag. He rattles it and he tells me to blow inside. I blow and he tells me to blow harder, I blow and he roars. A pang of fear hits. He closes his eyes and looks up, the only thing I see is his beard and the white of his eyes. He burps a couple of times then throws the contents of the small bag on the floor. A couple of tiny bones scatter; I recognize a dominoes piece, coins, some emeralds, pebbles and something that resembles a Santa Clause figurine.

He burps and pokes the bones with a stick as if trying to separate them. ‘I see a cloud; this cloud is dark but there is something that gives it light. You were supposed to have a bright future but there is a bad spirit that follows you everywhere you go.’ He burps then says vumani bo which is literally a command to agree. At this point I am expected to say siyavuma which means I agree. ‘You are not happy in your life and there is something that bothers you, vumani bo’. Obviously there is something bothering me, who doesn’t have something bothering them? I think to myself but for the sake of protocol I respond, ‘siyavuma’.

‘You have issues with your woman and at night when you sleep you have back pains that you cannot ignore vumani bo’. I wonder which woman he is talking about, but I actually do have back pains, maybe it is just because of sitting on a chair for at least 9 hours a day trying to finish my novel. Siyavuma. ‘You have to reunite with your father because your rift has caused divisions in your family. There has been instability in your life because the ancestors are not happy about the situation and they have unleashed their wrath through your siblings who are always sickly vumani bo’. Woah, there is no way he could have known that or maybe it’s just a lucky guess either way I want very little to do with my father. Siyavuma Siyavuma Siyavuma, at this point I just agree to everything he says and can’t wait for the consultation to end.

He gives me a couple of herbs to drink and some that I need to use to bath. He shakes my hand firmly and tells me to pass my greetings to my father when I see him. I leave the room and the sun is already preparing to rest behind the slow moving traffic on the M1 freeway. The weather, yes the weather is sulky as a woman on her period. Clouds hang low as if they have offended the sky and my spirit is heavy as a corrupt politician’s stomach. I should have confessed to Bab’Mkhize what I came to him for. Have I no regard for his vocation? Have I really no regard for culture anymore? I grew up believing in these customs, how could I have had such thoughts about him when he was genuinely trying to help me. I pass by MABONENG again and I realize that I am no better than the giggling blacks sitting there, we are all lost and trying to find whatever to make things make sense. It is better when it begins with acceptance.