The raging debates on the electoral bill in South Africa highlight the need for critical public discourse on the democratic deficit in representative democracy, particularly the social distance between political, public and government leaders and the citizens.

Waves of public protests, the decline in the number of people who vote in local and national elections and the increase in independent candidates and civic bodies that opt to contest local government elections indicate that a large section of the population feels non-represented, underrepresented and misrepresented or neglected, mistreated, rebuffed and castoff by political leaders, public officials and government leaders. This is the context that should inform public engagements on attempts to address the problematic requirement of the Electoral Act of 1998 that adult citizens may be elected to the National Assembly and Provincial Legislation only through their membership of political parties. The bill seeks to resolve this problem by expanding the Act to include independent candidates as contesters to elections in the National Assembly and provincial legislatures, by providing for the nomination of independent candidates to contest elections in the National Assembly or provincial legislatures and by providing requirements and qualifications that must be met by persons who wish to be registered as independent candidates. This is an important step towards ensuring the plurality of voices in the arena of parliamentary politics. However, this is not sufficient in addressing the democratic deficit and the enormous chasm between the political and socioeconomic conditions, conduct and lifestyle of politicians and government leaders and the living and working conditions of the rest of the population and the lived experiences of citizens.

Independent candidacy does not necessarily translate into independent political action. It does not automatically imply the political independence of independent candidates from the interests of the corporate and the dominant politics characterised by hierarchy and lack of meaningful and active direct and indirect participation of people in decisions, policies and programmes that affect their lives. Independent candidacy and the mushrooming of civic and social movements that contest elections do not certainly represent a break with the dominant neoliberal, pro-capital and anti-people political economy trajectory that treats social policy and social security as a luxury that can only be entertained after the so-called trickle-down effect of economic growth or as an irritable add-on to give the system a humane face and to contain the anger of the poor and subaltern. There is a high likelihood that many of those who will participate in elections as independent candidates or on the ticket of civic and social movements or so-called independent parties would be individuals who either could not make it on the slates of various mainstream political parties, have lost favour within their political parties, are simply looking for a career in politics or are a proxy or lobby for a variety of economic and ideopolitical interests.

The limits and de-limits of a constitutional liberal representative democracy cannot be understood outside the realities of the social structure and the extent to which social stratification and power and social relations have an influence on the social, political, cultural and economic currency and resources that facilitates or disables meaningful participation in cultural, social, political and economic life and appropriate structures and processes. The classical Marxist notion of class as defined by property and not by income or status and other relations of power and privilege is inadequate for unpacking the imprints of class position, class affinities and social privilege on the conduct of those elected into positions of leadership and authority in government and related institutions. The reality is that overt and covert forms of social disenfranchisement and capture of the state, culture, politics and economics by exclusive and entitled minorities thrive on an intersection between inequities, injustices and forms of oppression (i.e., exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism and violence) based on class, race, sexuality, disability and various forms of othering and objectification of people and reification of social reality. Therefore, there is a need to expand classical Marxist delineation of the social classes as the bourgeoisie, proletariat, petite bourgeoisie, and lumpen, landlords, peasants and farmers with categories that indicate current realities. These realities include the pervasiveness of the gig economy, uberization, casualization of labour, informalisation of labour and precarious labour. They include a modern and veiled form of indentured labour in the form of the illegal employment and super-exploitation of vulnerable and unorganizable immigrant labour. These realities have led to the prevalence of the uberat (i.e. third person) in the world of work. They have also led to the prevalence of the outworker, the informal labourer and the precariat as a sort of sub-category of the working class. Moreover, the upsurge of the gig economy has increased the number of freelancers, consultants, independent contractors (appearing similar to conventional employees but being independent), temps (temporary independent contractors), and seasonal workers who provide temporary services as independent contractors. In addition to these realities, are the specific conditions and experiences of women, people living with disability, and the lesbian, bi-sexual, gay, queer, transgender, intersex etc (LBGQTI+) community concerning political participation and general participation in cultural, social, political and economic life.

In examining the social structure of society and the different forms of social stratification and social marginalization that need to be taken into account in examining power and social relations that inform access to and participation in political structures and processes, it is important to look at both the universal and the particular. Thus, an examination of the specificities of South Africa’s social structure is necessary to inform our analysis of the democratic deficit in South Africa.

Using the official Upper Bound Poverty Lane of R1,136 per month - below which households are unable to meet their basic needs - to differentiate the poor from the non-poor, the National Income Dynamic Study (2008-2017) identified the five social classes in South Africa as the chronically poor, the transient poor, the vulnerable middle class, the stable middle class, and the elite. The findings of this study indicate that between 2008 and 2017, 48.8% of South Africans (nearly half of the population) were chronically poor, 12% of the citizens constituted the transient poor, 15% of all households were in the vulnerable middle class, and only 21% of households were the stable middle-class. Notably, according to this study, only 3% Only 3% of South African households could be classified as elite, which is defined as having a level of household expenditure higher than two standard deviations above the mean. Importantly, even 12% of the households falling under the stable middle class had a spell in poverty during the period of the study. However, the unequal power relations and high levels of inequalities are such that the tiny elite and the stable-middle-class are likely to dominate the political field as much as they dominate the economic field because of the cultural, social, economic and political resources and power at their disposal or their capability to access, influence and control political structures and processes. This explains why the debate on the electoral bill and the democratic deficit in South Africa are centred on independent political candidacy that on developing and enhancing mechanisms of popular democracy and direct and indirect participation of the people in the structures, processes and programmes that affect their lives and, on the check, and balances against the excesses of the state and the empire-building manoeuvres of the social and political elites who hold or influence state power.

One could argue that South Africa is an uncanny dictatorship of a political elite or middle class that use a system of patronage, social grants and elusive promises of service delivery and a better life for all to enlist and abuse the underclasses as voting cattle. This explains why the under-classes, despite being the most downtrodden sector of society remain the largest voting block that keeps the corrupt political elite in power, and in some instances, are willing to kill and die for the political elite or are misused as foot soldiers for the social and political elites who either want to access the levers of power or to keep their hands in the cookie jar that the state and public institutions have become. The attempts by the South African government to portray workers’ demands for a living wage as inimical to job creation and service delivery to put the employed and the unemployed against each other, give credence to the supposition that South Africa is a sort of oligarchy in which the dictatorship of the political elite (constituting most of the Black middle-class) is propped up by the votes of the under-classes. There is enough experience and evidence of politicians and those who aspire to a career in politics appropriating public sentiments and public support to ascend to power in the name of the people and ostensibly on behalf of the people but never returning power to the people once they are in political office. South Africans have seen many people who are either from poor working-class and underclass backgrounds or profess affinities to the working and underclasses who became dogmatic in preaching and implementing anti-poor policies and programmes once in power.

By now, South Africans know that many who come from the townships and rural villages use being voted or appointed in local, provincial and national government positions as a first-class ticket out of the township or village into the comforts of urban suburbia and the security of gated communities and electric fences, far away the madding crowd. Getting into office on the ticket of workers and communities has not prevented former civic and labour union leaders from being the most vociferous in shutting down labour and social demands. Suffice to mention the insults hurled against labour during the public service wage negotiations by former shop-stewards and ex-labour leaders, Enock Godongwana, Thulasi Nxesi and the pro-capital and anti-labour proclivities of another former shop-steward and ex-Secretary General of National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), Cyril Ramaphosa. This indicates that the reproduction and renewal of the ruling class often involve the recruitment of people whose background and posture suggest either opposition to or independence from the dominant oppressive, exploitative and corrupt political system into the ranks of political careerists. The political careerists are a bunch of people whose preoccupation and enterprise are to remain in political office or to access and amass the power, privilege and wealth that goes with government positions at all costs. This is the group that Gaetano Mosca referred to as the political class, defined as a minute group of ‘activists’ that is highly politically aware and active, and from whom the national leadership is mainly drawn.

It is true that, as Max Weber suggests, this group lives only for politics and makes a career off politics. However, in the current situation, especially in South Africa, people in this group ascend to power not necessarily because they are more politically conscious and active than the rest of us (as Mosca proposes) nor because they are policy specialists and experts on varied fields of public administration, as Webber asserts. The present crop of careerist politicians comes from a variety of social and ideological and political backgrounds and include people of non-elite backgrounds, and former social, political, community, cultural, labour and civic activists and individuals who emerged organically from popular struggles and got conscripted and co-opted into the political class through the workings of the system and the taste of the power, privilege and comfort that goes with career politics. They access and prop up their power through a variety of opportunistic, demagogic, grandstanding, patronage and despotic strategies. Their strategies vary from infiltrating, diluting, misappropriating and misrepresenting popular struggles and popular demands to myriad ways of bashing and throttling popular struggles and popular demands. In other words, the political class is largely part of the structures of authority, hierarchy and domination. Therefore, the focus of the debates on the electoral bill and other efforts to address the shortcomings of a constitutional representative democracy should not be merely about who can be a candidate for political office and how they can enter the political office.

If centred on who is eligible to contest for political and how the proposed electoral reforms will not facilitate substantive democracy. They will only be part of the mechanics of a symbolic democracy that serve to prop up the power base of the political class and to embellish the structures of authority, hierarchy and domination. On the contrary, as Noam Chomsky proposes, enhancing and expanding human freedom requires the dismantling of the structures of authority, hierarchy and domination.

This calls for electoral and broader political transformation that focuses on how to implant popular democracy in the political system and on the development of political structures and processes that enable public control and recall of those in political office. This requires extricating the electoral and entire socio-political system from the dogma of equating democracy and political development with liberal democracy. It demands the courage and boldness to non-dogmatically draw on a variety of more egalitarian political philosophies such as socialist humanism, anarchism and participatory democracy to push for political structures and processes that facilitate the entrenchment and expansion of forms of democratic empowerment that include direct and participatory democracy, direct action, self-activity, self-management, mutual aid, and various forms of organization and power beyond institutionalised politics and the dis-embedded economy to supplant the tyranny of capital and authoritarian state power.

Electoral reform aimed at addressing the democratic deficit inherent in a bourgeois representative democracy should explore how the political system can facilitate genuine equality, democracy, self-realization, collectivism, mutualism, community and solidarity. The electoral reforms should be linked to and be part of a broad agenda of expanding the liberal democratic values of democracy through a practical programme towards the socialist goals of human emancipation, personal and socioeconomic freedom and the democratization of the polity and the economy and all facets of life. Among others, such a program of action could include the development and promotion of popular sovereignty, citizens' assemblies, bias-free mass media, economic democracy, deliberative opinion polls, e-democracy, liquid democracy, participatory budgeting, participatory economics and solidarity economy. These should not be ends in themselves but means towards a long revolution aimed at social, political, economic, gender and environmental justice and a truly egalitarian society in which every human being can experience and enjoy safety, pleasure, relatedness, autonomy, self-worth and growth.

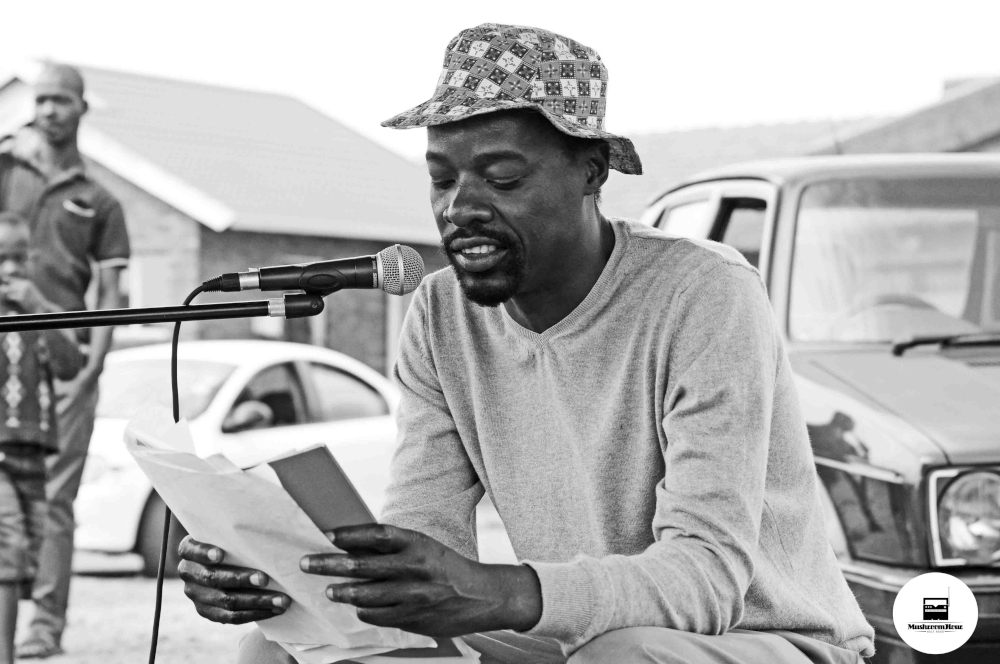

*Mphutlane wa Bofelo is a political theorist whose critical scholarship and activism focuses on socio-political development, leadership, strategy, governance and political transformation. His work draws on Black Consciousness, socialist humanism and Sufism.