Recall the last moment you were inspired. Feel a fresh film of air flow into you. What image do you see? What is the composition of that picture, the light, the colours? What is its soul? During a conversation with Lekgetho Makola, the head of the Market Photo Workshop (MPW), I felt a surge of fresh inspiration. In the sunlit room of his office, the light grew brighter as his eyes widened and he passionately said, ‘Yoh man! Hmmm, I want to cry when I think about images! Images guide us every day’. Wearing one of his signature African print shirts, in a bright yellow colour, his customarily pensive face suddenly lit up, and I smiled, I saw his expression glow from his spirit, illuminated by it. At the Market Photo Workshop, the soul of the image is the focus.

“The last image that I saw that really shifted something in me was the World Press winning image of the year. It’s of a Sudanese young man building up some kind of poetry song in the middle of the night, in the dark, but he’s illuminated by cellphone light or cellphone torchlights. And he’s surrounded by young people...

All that we see from Sudan is violence, and looking at this group of young people, it’s as if they are saying, “The future is ours”. And I work with young people so it’s just something that’s been in me, that image, since the beginning of the year.’

The World Press Photo contest’s winning image for 2020 brings into focus so much of what the Market Photo Workshop stands for; and in line with Makola’s vision. The Market Photo Workshop has a guiding ethos of developing human beings simultaneously as it develops the photographic skills of its students. Founded on the principles of workshopping, Makola, expands on its driving force:

“It means that the format of engagement is not lecturing, you know? It’s workshopping. Meaning that, whoever comes into the space, comes with lived experiences that are very important. They come with eagerness to engage their surroundings, based on what’s inside them”.

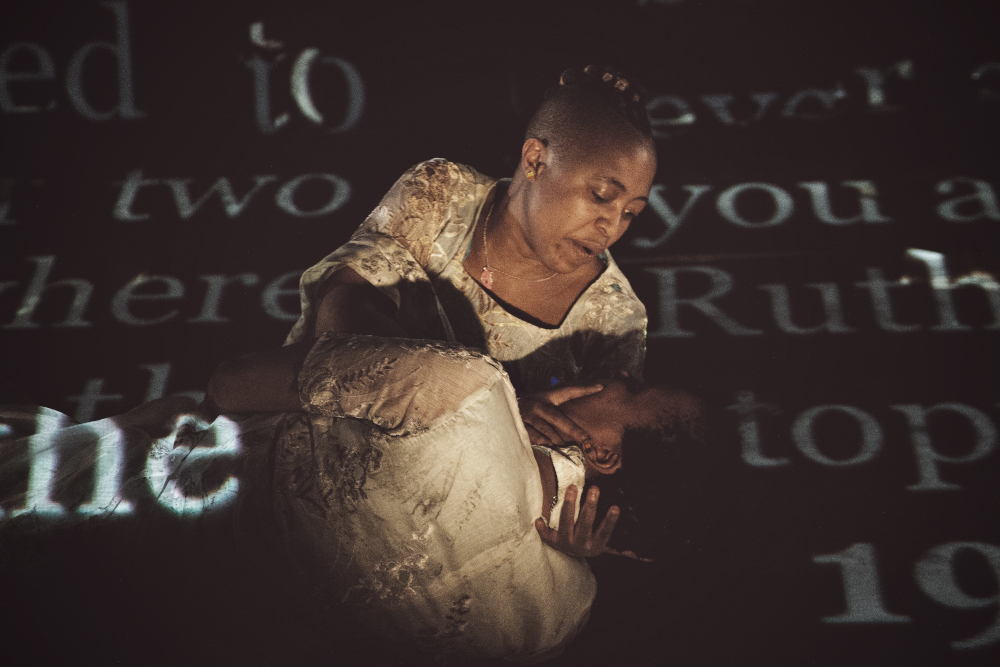

Thandile Zwelibanzi

Thandile Zwelibanzi

Students at MPW are encouraged to see themselves as being internally resourced. The school comes with a history of using photography as a transformative tool, from South Africa’s segregated history. It is now building a future of Pan-Africanist photographic artists who can play on the global stage. Students from across the world are beginning to acquire scholarships to get an education at the Workshop, and the Workshop’s two galleries are hosting world-class exhibitions of local and international photographic work.’

When I spoke to Makola, the outdoor exhibition of the 2020 World Press Photo Contest Winners was about to close that weekend. Not only was opening up access a significant part of curating this exhibition of visual journalism, but also (which lies at the heart of the Workshop’s vision) connecting the world. In order to ensure that students and staff “see themselves as part of the global photographic practice,” the Workshop hosts and curates exhibitions of both professional and student work. This works both ways. The professional space is brought into the classroom, and likewise classes are part of the world space. “We are in equal space. So that you begin to understand other world vocabularies all across the globe, but also begin to have a soundboard in terms of where you benchmark your style of work, your approach to different types of views… One begins to have a much wider reflection, in terms of the scope of the practice, and one begins to see how, in the future, they might format their trajectory.”

The 2020 World Press Photo contest winning image, by Yasuyoshi Chiba, does not instantly take one’s breath away. It reminds you of the deliciousness of breathing, in a year where breathing was made difficult in so many ways. It fills you with heartfelt hope for the future, in these dark times. It is what Makola, as the chair for the 2020 leg of the competition, and as the head of the Photo Workshop, describes as a critical shift in renderings of the image of Africa.

When Lekgetho describes what a Market Photo Workshop student leaves with, he is very clear that the aim is for them to, “see themselves as image-makers, as visual storytellers, using images as a tool or medium to shift perceptions, to impact, to engage, to ignite conversations. And to see that their audience could be anybody from their immediate street, wherever they come from, to somebody who’s based in South East Asia, for example, who can see that image and have some kind of connection with that image”.

Critical practice, critical thinking, critical reading, and ethical engagement with the environment or people being photographed, are all important parts of the teaching that goes on at MPW. The image-maker collaborates with people and spaces. They think about visual culture in the global South, in order to understand the ethics of telling other people’s stories, and even one’s own. “And in that, the photographic develops. Positionality is critical”, Makola emphasises. A student learns how to position themselves in the world, and how to position their work critically. He reflects on some of the past Market Photo Workshop students, and how important it is that the Workshop helps students understand the kind of photographer they want to be; whilst equipping them with the technical skills and resources that charge their internal resilience in a tough arts sector.

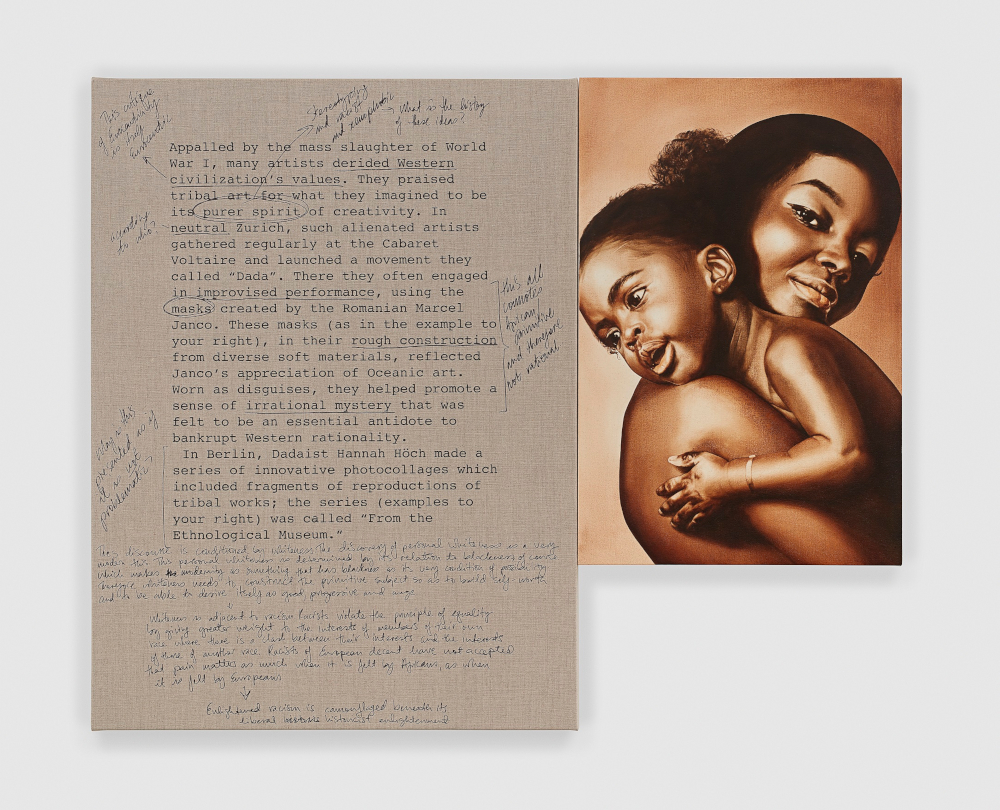

“We have this one guy, Themba Mbuyisa, who is doing amazing work in fashion photography. We have Zanele Muholi, who helps us think about how we can shift representation and bring that into how we think of the image… We have the opportunity to produce a number of Themba Mbuyisa’s who can shoot without sexualizing the human as commodities in the mainstream commercial space. Photographic artists can now think of themselves as artists who define themselves and redefine image-making.”

Themba Mbuyisa

Themba Mbuyisa

Makola has intentionally started using the term “photographic” at the Workshop, because he wants to stretch the art of photography beyond its borders. “Beyond the borders of countries, and beyond the borders of the frame itself. The photographic artist understands that, ‘it’s no longer about being the cameraman or camerawoman, where everybody just views you as this person who just ‘takes’ the image. Also, to engage those problematic terms like ‘capture’ and ‘take’ and ‘shoot’… that are still strong in photojournalist spaces. These are very colonial terms. They defeat the process of collaboration. The photographic allows us to think of the sheer artistry of constructing an image, just as much as we can think of the photojournalist as a frontline worker.”

“Yoh man! Hmmm, I want to cry when I think about images! …Images evolve us every day,” Makola continues.

“Think about that image”, he says with brightness in his shimmering eyes. His smile spreads with the intensity of his eyes as he visualises what he’s saying. “That image that you think about on sleepless nights, and you end up taking it, making it. And it becomes an iconic image that many people think about and reflect on, and have some kind of connection with. That image goes to some unthinkable community on this planet that you never thought your image could reach. That sense of reach! That sense of the soul that you embed in the process of making that image. When that image lives on its own, in a different sphere that carries your soul, you’re not removed from that image. It means that your soul gets accessed by millions of people.”

I can only agree when Makola says that photographers are our frontline and our backup. “When you think about the past, the photographic memory comes first,” he says. “That archive becomes a form of memory, but also a sense of guiding. It’s sense-being; what helps you get where you are going.” He explains how not only architecture, but fashion, and actual human experience, are framed by the photographs we have of the past that help us picture our futures. Also, that pictures help us know of experiences that we could never have access to. “Without images, it’s going to be a blank world. I mean blank, blank, blank.” For Makola, the fact that the arts sector has had a historical problem accepting photography as Fine Art is nonsense. “I believe that is bullshit”, he says with clarity.

Coming from a multidisciplinary background, Makola has brought an artistic vision into the way in which the Market Photo Workshop teaches the practice of photography. For Makola, the photographic artist (whether they shoot high fashion, landscape, portraits, or do photojournalism and so on) can be a diviner. Boundaries are meant to be pushed. “Photographers are our diviners. Ke ma dlozi-nyana. They are our soothsayers. They sometimes predict but also, at the same time, they store and archive our memory. Ultimately, it’s about communication and connecting the world. Images guide us. They connect our souls.”