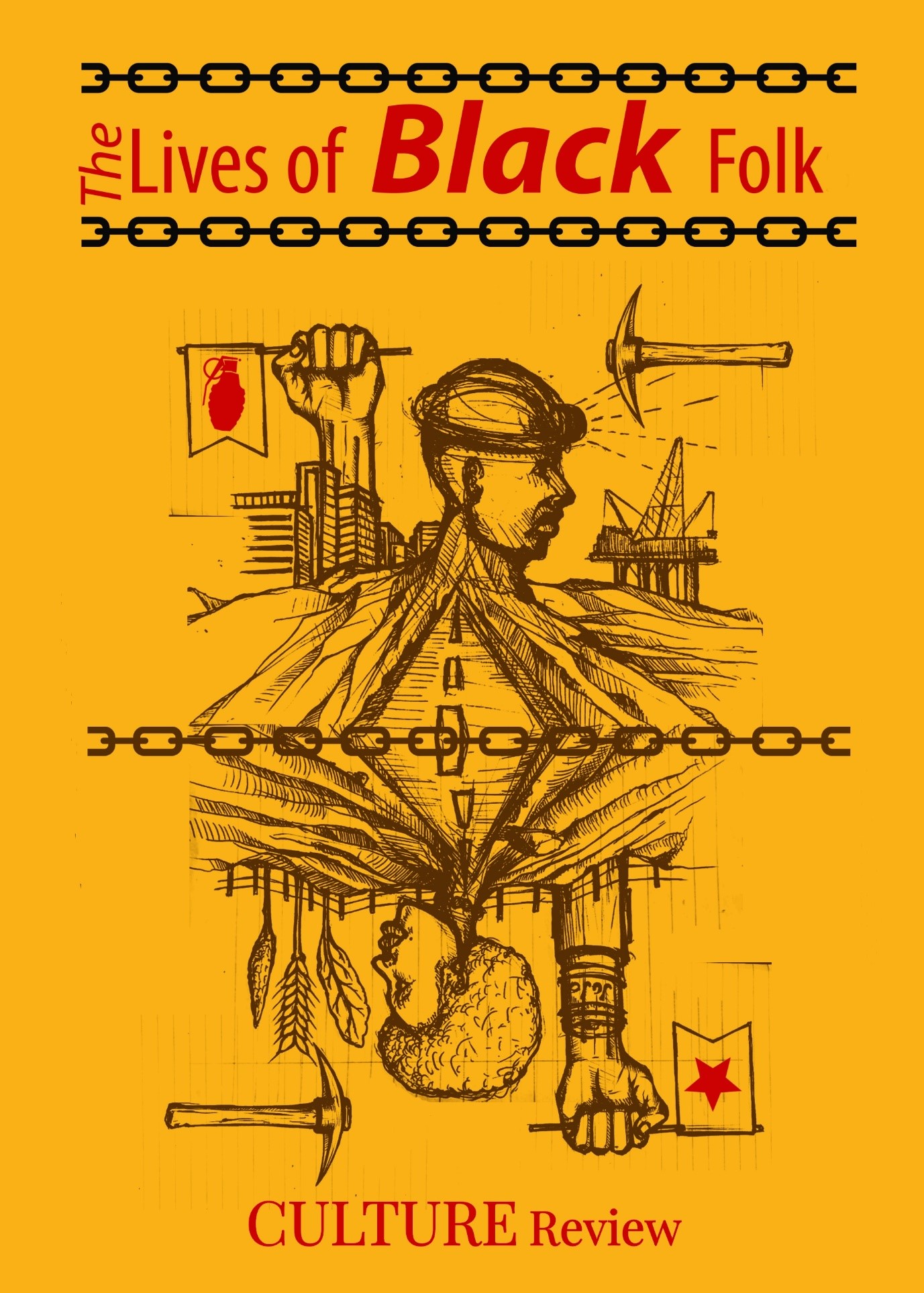

What remains when there is no justice? When hate is not named? What remains when the queers who have been murdered do not get their day in court? Emptiness remains; because grief is not allowed. Walking into the theatre for NO EASTER SUNDAY FOR QUEERS, is walking into a murky world. The auditorium is covered in a thin mist of smoke. The walls of the stage, as well as floor, are restless. Water is dimly projected onto surfaces, giving them an intangible air. And, a couple sits on an overturned pulpit, gently caressing one another, one playing with the scarf of their would-be wedding dresses. They are the ghosts of a lesbian couple, drowned in church on their wedding day, on Easter Sunday. The couple sits, a little too solidly in their bodies for ghosts but, the space is lifted by the thin fog of the now-burned down old church. The church is poetically symbolised by a set made of blackened wood. Debris, of pieces of timber and burnt hymnals are strewn across the floor. Bare beams reveal the old roof, now, without its ceiling. The poetry of the space is clear in its textures. Each element, a metaphor of the violence of the old church. Each theatrical element brings together the emptiness that remains, where the queer ghosts haunt our contemporary space: waiting for justice.

In the programme note to Koleka Putuma’s multiple-award winning playtext NO EASTER SUNDAY FOR QUEERS, currently on at the Market Theatre, Putuma and director Mwenya Kabwe write, ‘The alter is a cross and the subconscious a court room where the dead seek justice for a an act sin committed by their perpetrators’. A reckoning is staged, where the violence against queer people is tallied and those hiding behind scripture have to carry the cross of their sins for crucifying those who came in the name of love. The playtext acts as a Newer Testament. Poetry as testimony to homophobic violence.

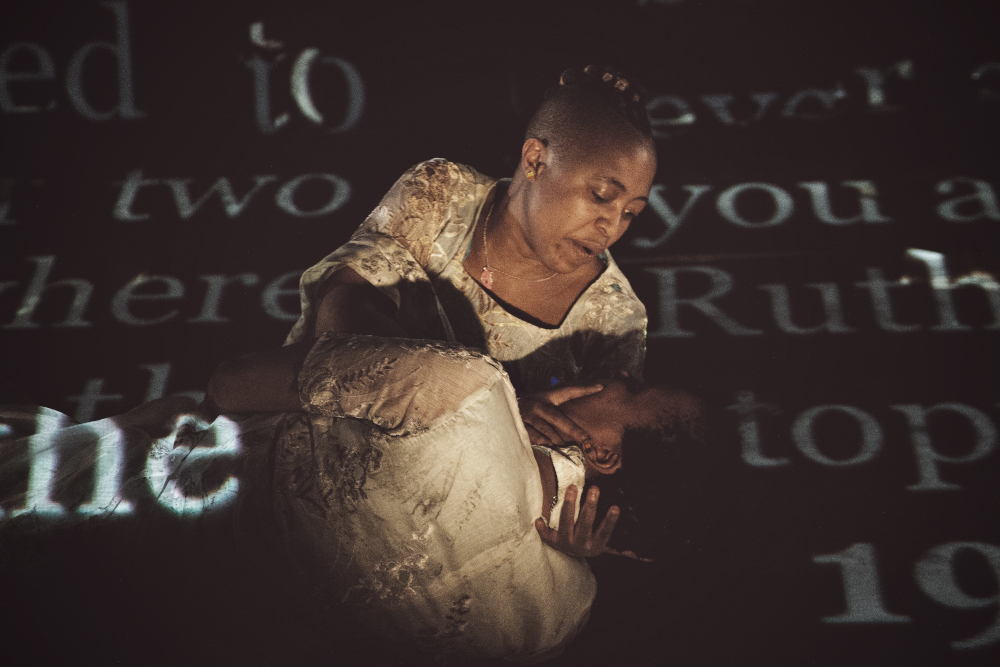

Mwenya Kabwe, who directs the piece, slides between calling the writing a play or poetry. The poetry, means, as Kabwe says, ‘There was no way to stage it traditionally. There is also so much going on that’s not spoken. There’s so much that’s not written’. And, while Kabwe is talking about the critical, purposeful gaps that Putuma places in the fragmented workings of this ghost world- an aftermath of ‘a sin committed by’ Christian perpetrators- there is also the experience of the emptiness of the characters onstage. Putuma, says the play is set in ‘the afterlife’. The experience of the piece is of an aftermath. The world created is one where something has happened. The world is derelict. The couple Napo (MoMo Matsunyane) and Mimi (Tshego Khutsoane) speak in disjointed speeches. They splice together the present with different histories; constantly interfering with the pastor’s singular biblical history.

In a wonderfully crafted moment when- straight out of Putuma’s stunning personal poem, of the same title- a club scene is performed with the incredible chorus of the Market Lab ensemble, filling the stage. Beyoncé blasts on. Beyoncé is singing Yoncé from her first overt feminist album. The pastor/father is still at his pulpit mixing up scripture with the reality that haunts him. Suddenly, Yoncé gets mingled into his garble. And, magic feminism seems possible for a split second. The scripture pardoning the pastor/father is made joyfully queer. But, then, the chorus of cross-dressed congregants that Kabwe choreographs as ‘the possible future’, leaves the stage. It is emptied of life again. Exposed in the empty nightclub Napo fears the world’s hate and refuses to kiss Mimi. Napo carries the too-many news stories of lesbians murdered and dumped that Putuma writes to. ‘There are just so many stories that you are asked to grapple with as you navigate queer life and the world’, Putuma sighs.

Kabwe, sighs and sighs and then let’s tears drip quietly from her eye when she’s asked about queer murders. Hate crimes. In staging the end of the play, Kabwe does not represent the violence of drowning, in Putuma’s writing. For Kabwe, the poem-play is ‘about two people who want to be together’ so, she relies on the visual and aural to manifest the violence because it is traumatic and ‘why would the gays want to see that?’ Kabwe uses the immersive projection to represent trauma. Lingeringly, the phrase “hate crime” is projected when Napo ends the factual retelling of her drowning, Napo’s statement: ‘The crime/ is still under investigation’, gets amplified. Here, Napo shows the only grief the actors perform.

Grief is not allowed in this aftermath poem-play. Napo and Mimi were not allowed to feel; while they lived. They were killed for feeling for each other. Putuma’s writing empties the ghost-characters of grief. Loss is not put into the poetry. Violence cuts through love at every point. Grief requires love. And, in this world that kills, hate overrides. Kabwe attempts to focus on the unwritten love in her directing but, the characters end up too easily intertwined throughout the play. Kabwe attempts to ensure ‘they will be together. Be together in a very simple way actually’, but the actors seem mostly untethered in their roles. Tshego Khutsoane’s magical moment is when she is able to work from her emotive training. Mimi imagines what it would be like to pay lobola for Napo. ‘Lesbian lobola’, she dubs it, to Napo’s questioning of the fantasy. Khutsoane meets the mandate of simplicity in performance when, as Mimi, she says she would tell Napo’s father, ‘I love you…I love you, Napo’. And, she leaves the space full for the first time. Full of love.

What remains upon leaving the world of NO EASTER SUNDAY FOR QUEERS is the imagery. Putuma’s writing sits in the emptiness of what cannot be retrieved. Kabwe leaves the audience with a choral cold-burning cough of drowning/choking/possible-grieving. Emptiness is met with possibility. Etched into the debris, is what remains when queer people are killed and not grieved; when justice is not received.