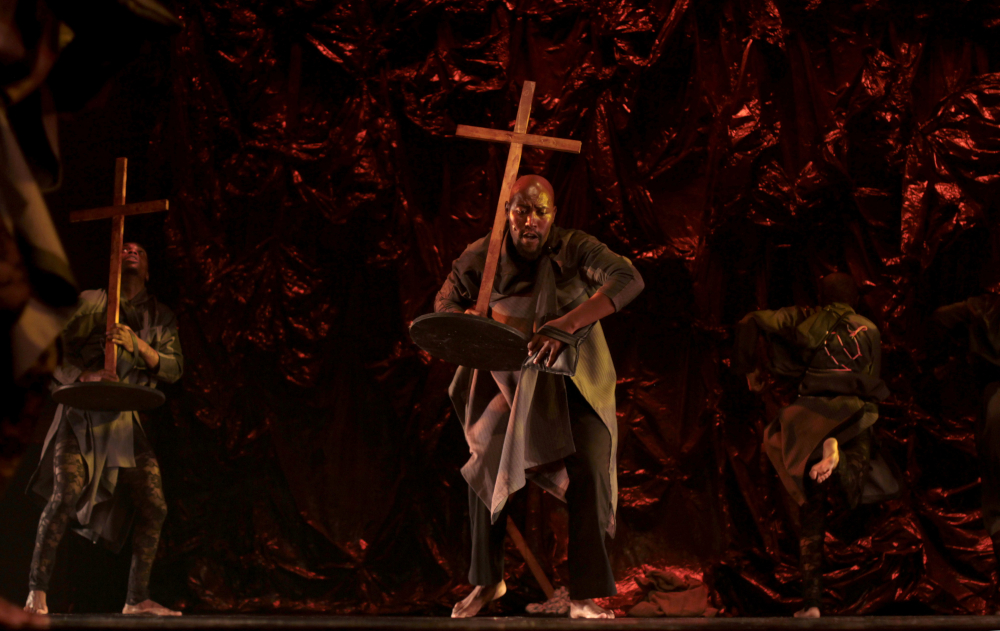

Taking the taxi home, after watching Makhafula Vilakazi’s Concerning Blacks, the people looked enchanting once again. It was as though the performance experience opened up the poetry in every black face from the Jo’burg Theatre to Bree and the rest of the way home. Vilakazi writes acts. The poet, like a playwright, writes characters that speak in self-revelatory monologues. The poet, unlike most actors, does not invent these characters; he brings real people to new life.

Standing with his knees bent and arms slacked at his side, Vilakazi evokes the drunken uncle in every township. A mournful landmark. The uncle who stands at the corner ever-drunk and spitting words that are slightly too loud is realised for us who walk past him, as real as our own hopes and ambitions; our own lusts and awful contradictions. Through Vilakazi this uncle is a poetic drunken master. More than just being the title of that fantastic Jackie Chan film, from our youthful past, the drunken master is also a relished role in the craft of oriental theatre. It is a difficult one to master because of its contradictions; the drunken master is sloppy but quite clear in his message. The drunken master is the ultimate underdog - always underestimated, he can pierce to the point of something philosophical because the alcohol removes the daily veil of decorum. The drunken master can narrate experiences with the truth of words that state things as they are, as they are called, rather than by needing metaphoric disguise. It is this role that Vilakazi mobilises to remind us of who we are, and not just who we want to be. In a world where much activist art dictates political correctness instead of seeking where the politics live, with their contradictions, Vilakazi’s drunken master shows real people so we can know the work that still needs to be done inside us.

Makhafula Vilakazi is not an actor. He knows exactly who he is talking from. He lets him speak through him for the benefit of our getting to know more of who we are by getting to know this person. The person, who, all too often, becomes a mere character at our events and ceremonies or as we walk past him on that same street corner he seems to always have been standing on. He makes us pause to listen.

Concerning Blacks relays a deep concern with black living. It is not a mere concern for blacks. It is concerned with blackness itself. Njabulo S. Ndebele said the pity with protest literature during apartheid was that it became the work of spectacle. His seminal essay Rediscovery of the Ordinary called for exactly that, a recollection of the everyday living of people through these times. The concern that Vilakazi shows with the detail of the real words and tones and sounds of the personas that he writes, is a precise rediscovery of the ordinary. Vilakazi’s monologues are poetic acts with a quality of being enchanted with the detail of real life. It is the poetry in the everyday reality that makes these poems protest literature of the highest calibre. The protest brings the mass issues, for which the names of struggle icons are invoked, home to where the struggle is also lived; by those who die unknown.

He begins Concerning Blacks with the incantation of the godly in each womxn selling produce to make a living for themselves and their families. He speaks as though he has walked past so many of them and somehow seen each of them. They are not just a mass in size and multitude. They are individual. The following poem is spoken through the voice of a womxn. She is ‘Infecta’. She goes through many an ordeal and she is full of wrath and seeks to wreak vengeance by infecting as many people as she can. She infects, also, the men, who attack her on a street on her way somewhere. The contrast of the poems is stark, raw, and real. In ‘Sfebe Ungipatrekile’, we travel with a man who is drunk with love. The womxn uses him and he hurls the vilest insults in her direction to cover his sobering pain. Then in the following poem, ‘Sambrella’, we soar on the many highs of black love. Love itself seems to be intoxicated with itself as it elasticises story to story, weaving through to an epic love poem. The love scorned in the previous poem seems to transform in the contrast of love that works under this massive Sambrella that colours every person described in a warm glow; as through a rainbow-coloured umbrella covering someone from the heat of the sun. It is with this glow that Glen Dlamini seems to write the love letter to Queen Elizabeth. One of Vilakazi’s well-known character poems. Glen Dlamini is an unassuming man who knows he is a King even though it seems ridiculous when all he does is stand in one spot- drunk. Yet, somehow, he has the sense that before history turned and this became his unmoving path, he had the potential to be King and so, perhaps the colonial matriarch can grant him that now; when he can no longer lay claim to any land in his country. After this significant use of humourous pathos, the rhetoric of Vilakazi’s Concerning Blacks takes a sharper line on the issue of blacks that are politically concerning. His drunken master takes hold of the stage for the rest of the show and even the sweetness of the singing of Samthing Soweto, that had accompanied the poems in the first half shifts and the band’s tones grow a somewhat darker bass. A black man begs a fellow black man not to forget him now that he is prospering; Dela Rey, the general, is asked to sort out his people; a man mourns his own mortality; and South Africa is called amasimba because of its xenophobia. By this point, the politics sear and yet it is a softly sung Nkosi Sikelela- from the original version- that holds the moment and gets the crowd on their feet in solemn protest prayer.

Paradoxes of beauty in despair fill the spaces in between each poem. In some way, each poem calls us back to ourselves and our own contradictions. The music between becomes a salve for all the hurts we feel and sometimes awfully impose. And, so, even though it becomes frustrating to watch Vilakazi read almost every poem, as he - at one point- even has his face covered by the page throughout an entire poem; the performance is held in a mood of musical space. In the last poem, Ulele, drunkenness is a sleep-state. It says we must recognise drunkenness in all of us who choose to sleep to the concerns of fellow black people. It is a critique of calling for revolution in languages that are not our own; whether they be Shakespeare or Marx. Makhafula Vilakazi’s poetry performs its protest through people rather than sloganeering- which is effective, also, in its own necessary spectacles.

Vilakazi’s is a peoples’ poetry. It asks us to see poetry in every human being’s living, if we are to fight for true freedom.

This review originally appeared on Nondumi Solwazi