At its 2008 General Synod, the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa considered a report on the church’s stand on the question of sexual orientation and nonconformity.

That was a moment, in my view, in which this church, who had declared apartheid, its biblical and theological justification a heresy and led the ecumenical movement in doing the same; who in formulating in 1982, and adopting in 1986 the Belhar Confession as a new standard of faith, faced its greatest challenge since confronting apartheid. Central to the Confession are our unity in Christ; the reconciliation wrought by Christ, and the justice demanded by God. These three things.

I was the convenor of that task team and presenter of the report at the synod. It was one of those utterly shattering, fundamentally life-changing experiences. After a hostile, and theologically disturbingly crude, debate, the synod rejected the report, its contents, its conclusions and its recommendations calling for justice for LGBTQI persons and referred the report for reconsideration. Even though the words, “another, more anti-gay report” were deleted from the amended version of the original proposal, the intention could not have been clearer.

What was striking and shocking, even though hardly unknown in debates on this matter it seems, was the stridently hostile tone of the debate, the blatant homophobic language that dominated the discussion all through the afternoon. Speakers who took the floor did not even attempt to disguise their contempt. Some spoke openly of LGBTQI persons as own flesh because of their different sexual orientation?

There was no awareness of our Reformed tradition that is so deeply rooted in justice, in the belief that every wound of injustice inflicted upon any of God’s children is a wound inflicted upon Godself. John Calvin, the father of the Reformed tradition insists that “Scripture helps us in the best way when it teaches that we are not to consider what [human beings] merit of themselves but look upon the image of God in all [of us], to which we owe honour and love… by virtue of the fact that God forbids you to despise your own flesh”. Striking in Calvin is the degree to which he begins from the claims of the Other, and that claim is grounded in the fact that we are kinfolk, each of us unique in our “iconicity” which in turn is grounded in our imaging of God.

What called forth the most ire by far, however, was the fact that the report interpreted the Belhar Confession in a way that called for solidarity with, embrace, and inclusion of LGBTQI persons, in the same way that the Confession calls for justice and dignity for people of colour in a racist dispensation. Probably the best known words of the Belhar Confession are the words that echoed in the church’s conviction that “the church should stand where God stands”: namely with the wronged, the poor, the destitute and powerless against the powerful; and against any form of injustice and oppression. The report took the view that these categories included those despised, rejected and marginalised as a result of their sexual orientation.

That synod was, in more than one way, one of the most devastating experiences of my life. So when this conference speaks of a “backlash” I think I know exactly what you mean.

The Other Foundation

The church should stand where God stands: with the wronged, the poor, the destitute and powerless against any form of injustice and oppression.

How could the church that took such a strong stand against apartheid display such blatant hatred and hypocrisy (and) deny for God’s LGBTQI children the solidarity we craved for ourselves? “animals”, “not created by God”; of bestiality and of LGBTQI persons in one breath, all of which as being a “scandal” and “stain” upon the church.

It was an experience that had left me shaken and disoriented: how could the same church that took such a strong stand against apartheid and racial oppression, that gave such inspired and courageous leadership from its understanding of the Bible and the radical Reformed tradition; that had, in the middle of the state of emergency of the 1980s with its unprecedented oppression, its desperate violence and nameless fear given birth to the Belhar Confession that spoke of reconciliation, justice, unity and the Lordship of Jesus Christ, now display such blatant hatred and hypocrisy, deny so vehemently for God’s LGBTQI children the solidarity we craved for ourselves in our struggle for racial justice, bow down so easily at the altar of prejudice and bigotry?

We who had rescued the Reformed tradition from the heresy and blasphemy of the theology of apartheid of the white Dutch Reformed Church and forged a new identity for that tradition in struggles for justice and oppression, leaned so heavily on the exodus metaphor as inspirational in the struggle, take that paradigm one step further? In other words, will those who stood so firmly on Exodus 3:7, “I have observed the misery of my people who are in Egypt; I have heard their cry... and I have come down to deliver them”, now as wholeheartedly embrace Ex.23:9: “Know the heart of an alien, [meaning the Other] for you were aliens in the land of Egypt?” Will they understand that LGBTQI persons are made into aliens in their own land, strangers in the church, exiled from our love and consideration? Will they understand that all outsiders, like they once were in the country of their birth, are worthy of inclusion, and that that inclusion is God’s intention? Will they understand that LGBTQI persons are not outsiders “by nature”, as if God willed it so, but that are made into outsiders by our sinful acts and attitudes, by our hateful rejection of those God has had the temerity to make in God’s image, but not in ours?

LGBTQI persons are not outsiders “by nature” as if God willed it so, but are made into outsiders by our sinful attitudes.

Taking a stand - A Call to Action by the Church Against Injustice Towards LGBTI People

Moreover, these questions are raised within a context of great urgency and against the background of growing homophobia or more properly put, bigotry, and an exacerbating climate of murderous violence aimed at LGBTQI persons in Africa in general, but increasingly in South Africa as well.

Uganda now holds perhaps the dubious distinction of being the most openly anti-LGBTQI country on the African continent, with its legislation severely criminalizing same-sex relationships. Kampala’s Rolling Stone newspaper has captured the attention of the world with its “exposure” of especially gay men and its banner headline call to “Hang Them!” Giles Muhambe, the publisher, says: “Whatever happens to gays is a result of their own misdeeds”. Meanwhile, at least one gay person has already been brutally beaten to death in Kampala. In South Africa, LGBTQI persons are victims of all kinds of abuse and violence, including murder and so-called “corrective rape” by gangs of thugs, especially of lesbian women, a perverse kind of “therapy” to make her change her “deviant” ways now that she knows what “real” sex with “real” men is like. This is on the increase despite South Africa’s constitutional protection of the rights of LGBTQI persons, including their right to marriage. For us this constitutes an immediate crisis, since it is, for God’s LGBTQI children, literally a matter of life and death.

Behind the fierce Ugandan legislation is born-again parliamentarian David Mahati, backed by the powerful and influential, but shadowy US right wing Christian group, “The Family”, organisers of the “National Prayer Breakfasts”, an event that no US president since Eisenhower has dared miss. Mahati believes he is chosen by God to “deliver humanity from this calamity.”

When then President Zuma appointed that rabid homophobe, journalist Jon Qwelane as South Africa’s ambassador to Uganda of all places, there was huge public outrage. And rightly so. It made me proud. But what made me inexpressibly sad was that my church, the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa, did not join that chorus of righteous outrage. We could not, dared not, because just the year before we showed that we had shown ourselves just as rabidly homophobic, filled with just as much hatred, drenched with just as much hypocrisy and bigotry as the designated ambassador and the man who appointed him.

Our hateful rejection of those God had the temerity to make in God’s image, but not in ours, shows how far we are from the Kingdom of God. The joy of belonging to the community of believers is not to be denied any member of the body of Christ.

Just the other day, the Kenyan Supreme Court reconfirmed a colonial-era law (brought there by the British, not confirmed as an authentic African tradition rooted in the wisdom of Ubuntu) that legitimates discrimination against and criminalisation of nonconformist sexual orientation, love, and life-style. In the forefront of the battle for this shameful outcome were the Christian churches. This stance may open the door for Kenyan churches to get more funding from the number one homophobe, misogynist and war-monger in the world in the White House, but it surely closes the windows of heaven through which pour the blessings of a compassionate, justice-loving God, just as it closes the possibilities of joy within the Christian community for the LGBTQI children of God who looked in vain to the church for the embrace of love and community they so richly deserve.

Refiloe Lepere

The joy of belonging to Christ and to the community of believers, of knowing one’s rootedness in the love of Christ and the love of the family of Jesus; the joy of sharing that community in its fullness and the sharing of the fullness of one’s own humanbeingness within that community and in the world: that joy is not to be denied any member of the body of Christ. That sense of belonging in Christ, and as a consequence with each other, is unbreakable and untouchable by any human law or ideology, by cultural or personal prejudice.

It is within this context also that Belhar calls upon us to remember that “we are obligated to give ourselves willingly and joyfully to be of benefit and blessing to one another since we share the one faith...” We are not offered this as an option we might or might not take. We are not forced, cajoled or tricked into this: we are, as followers of Jesus, obligated. As true as this is of our racial relations, it is true of our other human relationships as well, especially in the church.

The foundation of the Other’s existence is not the difference of skin colour, gender, culture, or sexual orientation for that matter. Rather it is their humanbeingness, their being created in the image of God, sharing humanity in all its fullness with us. We dignify both the difference and the togetherness with our respect and love and the embrace of our common creatureliness as image bearers of God. The dignity of difference is the dignity of personhood and being part of the greater human community. This is what the church celebrates and embraces. And this embrace is not the glorification of our ability to be “tolerant” as long as our cultural domination remains intact and normative. It is the celebration of the inclusiveness of the embrace of God.

The lack of unfettered compassionate inclusivity is a deliberate rejection of the renewal in Christ in which “there is no longer Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave and free; but Christ is all and in all.” (Col. 3:11) On the contrary, it is our calling, gift and obligation to live together as reconciled community. There is nothing that falls outside of this call and gift; nothing that makes us “despair of reconciliation” because we cannot despair of the work of Christ.

This goes indeed far beyond the issue of race. This addresses quite profoundly the historical and actual contexts of oppression, rejection and exploitation of LGBTI persons, but also people mentally and physically challenged (“disabled persons”) and women. It begins with the recognition that Belhar’s understanding of the diversity mentioned above is a holistic, positive, enriching one, as opposed to the apartheid-inspired understanding of “diversity” that is negative and therefore leads to “natural” separation that should first be enforced by law and then sacralised by the church, as was the case under apartheid.

Churches often take resolutions “embracing” LGBTQI members. Embrace is not the glorification of our ability to be “tolerant” as long as our cultural domination remains intact and normative.

But listen to the language Belhar uses here. Belhar not only advocates “embrace” as an act of love and justice, it also disputes against an understanding of “diversity” that is abused for the values and cultural bent of the dominant; or conversely, a diversity that is considered to be contrary to the will of God, but enforced on an unwilling church by a secular Constitution, as is now the case in South Africa with the recognition of sexual diversity.

Rejection of Persons

The church expressly celebrates the diversity that affirms humanity and welcomes it as a reasons of negativity and rejection, as in apartheid and homophobia, instead of a diversity that celebrates the Other and the richness of difference. The diversity that the Confession rejects is the diversity that seeks to find a negative “otherness” that comes with enmity, distance, aversion, discrimination, degradation and domination. That is the “diversity” as defined by the apartheid ideology, which becomes the cause for separation, inferiorization, and exclusion. In doing so it eliminates dignity and the bond of humanity. To absolutize this diversity is to make it the foundation of the existence of the Other and so to pervert the meaning of genuine diversity. It is the breeding ground of injustice and demonization. The diversity that Belhar celebrates is the diversity that comes from celebrating both the richness of the creation of God and the dignity of the difference we see in the Other

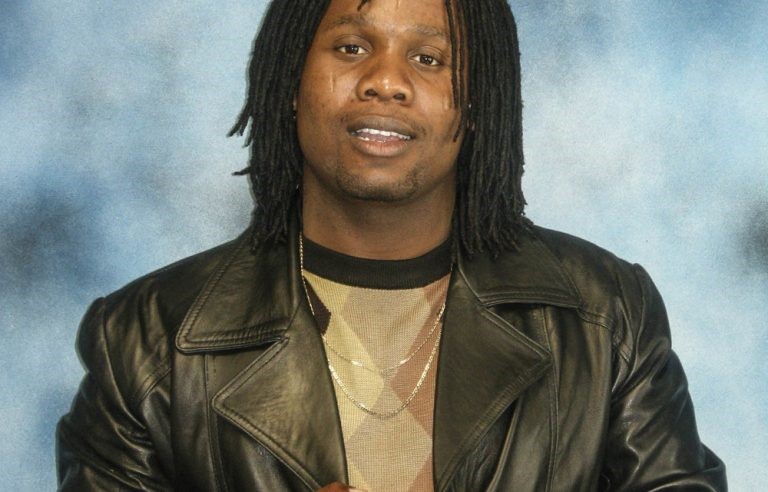

About The Author

Allan Boesak is Extraordinary Professor in the Faculty of Religion and Theology at Pretoria University. He studied theology at the Theological Seminary of the Dutch Reformed Mission Church and was ordained in 1968. In 1970 he started advanced studies at the Theological University at Kampen in the Netherlands, and was conferred a Doctor’s degree in Theology in June 1976.

His involvement in public life and South Africa’s freedom struggle began in 1976 when he returned to South Africa a week after the Soweto uprisings to become chaplain to students and minister in Cape Town.

In 1983 he called for the formation of the United Democratic Front which would grow into the largest, nonviolent, non-racial anti-apartheid formation in the history of the struggle. A fervent believer in direct, nonviolent action, he became its most visible leader at home and abroad. He worked with President Nelson Mandela, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Rev Frank Chikane and an array of world leaders to end apartheid.

Allan served the church in various ecumenical positions, including as Moderator of his church, Senior Vice President of the South African Council of Churches, and President of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC). Under his leadership the WARC declared apartheid a sin and a heresy, and suspended the two white Dutch Reformed

churches in South Africa for their moral and theological justification of the apartheid system. Over the years, Allan became a world renowned liberation theologian and a coveted speaker at world events.

He has received thirteen honorary Doctor’s degrees and more than twenty awards, among those the Robert Kennedy Human Rights Award, the King Hintsa Bravery Award from the Xhosa Royal House, and the Martin Luther King Jr. Peace Award. He was recently inducted into the Martin Luther King Jr. International Board of Preachers at Morehouse College, the only African to have that honour.

The author of 22 books, most recently Pharaohs on Both Sides of the Blood-red Waters, Prophetic Critique on Empire - Resistance, Justice and the Power of the Hopeful Sizwe (2017). His newest book, Children of the Waters of Meribah, Black Liberation Theology and the Miriamic Tradition, will be published in 2019. Allan has taught across the world, and continues his teaching and preaching, while remaining active in global struggles for human rights.