“It can only be mine in that I share it with you”

-Fred Moten

“The King will reply, ‘Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me’”. (italics mine)

-Matthew 25:40

When I grew up, I never had much time with books, not that there were any lying around at home, unattended and less loved but simply because I grew up in a home and rural place wherein seeing a book was extremely rare. It only had to be during school time that one had to see, feel or read a book. I do recall vividly in my 10th grade, when we did literature reading during English classes, the first book we laid our hands on, the first we learnt to let our souls walk and live on, was an anthology of short stories titled, The Soft Voice of a Serpent. One of my best in that anthology had always been the classical short story titled, The Dube Train by Can Themba.

Books had been a vital point of departure for many to make sense of, and understand the world. Without access to books in my early days up to secondary schooling, something else had to fill the void. Another thing had to be my point of departure in my journey with the world. Music. That is the term in short, music. Music is what kept me in touch with the world. It became an introductory tool as a form of orientation into the world. There is a man who comes to my mind whenever such thoughts make rounds in my head. That man is the reason as to why I have undertook a task to write this, whatever one may term it.

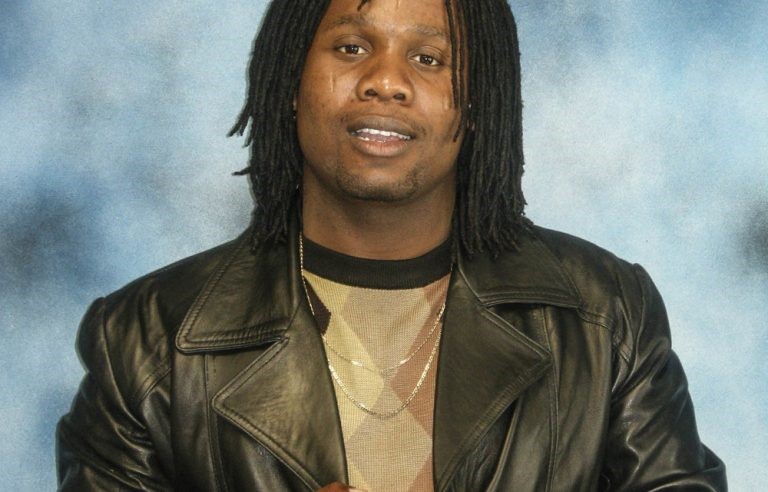

That is not really my concern, rather my concern is that it is written and out there, so someone, perhaps like me, without books but music, may know that there was once such a man, who did it all for ‘the least of these brothers and sisters’. Mgqumeni is the man of interest in this task I have undertook to carry out. His music has been great yet also an inspiration to many, a source of hope and courageous voice which never tired to tell of the societal issues as they affect black people in South Africa.

It is the cultural theorist Fred Moten, who a year ago delivered a sermon at the Trinity Church in Wall Street, in that sermon he spoke beautiful and poetical about fellowship. A term which can be defined as a feeling of relatedness if one takes the lexicographical offering. Mgqumeni’s musical work can be taken as a call to fellowship, a call to gather – in order to think and act in oneness. For he knew, just like Fred Moten knew in that it is only when he shared his work that it could hold as his.

It is in this form amongst many that one can express gratefulness for the artistic beauty and relentless actions by Mgqumeni to keep his rhythm in touch with the realities of this world, of those close to him, those who lived their life with endless groans and moans. Us black people who the world had long time ago raced black and who the world crashes against, the damned of the earth. These are people that may see and listen to some of his songs as some sort of an autobiographical note of their lives. He represented at best what Ncedisa Mpemnyama correctly argues that it lacks in the South African art space, the fusion of the artistic and the political or “the marrying of the two” as he utters the words himself .

In his music, an account of events as they unfold in our society is present. Ranging from the warnings about catastrophes upon black people to come and present, and the dangers in the aftermath if we’d choose to keep ourselves in the fetishistic disavowal cave. I recall someday sitting at home. Exactly about a few years after he had passed away. I, my older brother and his friends packed in a hot room, with the sun blazing non-stop outside. Our eyes were fixated to the TV screen as we watched with appreciation and love the DVD of an album by Mgqumeni titled, SMS.

During the session I had said something that my brother was unfortunate to totally mishear. I’ve said 'ubafo lona' (this is my brother) and my brother thought that I had said 'sewafa lona' (he is dead). He stopped the video, looking with angrily eyes and face that looked not far from exploding at me; he shouted 'uMgqumeni usazophila ingunaphakade!' (Mgqumeni will live forever). As he shouted I could see anger taking over his body and emotions like one possessed by an evil spirit full of rage. Only the fast racing sound of his heart could be heard, as the room had seemingly lost itself in silence. We watched and did nothing. No word could be sufficed to counter such a moment. My brother truly wanted uMgqumeni to live forever.

Although his was a mishearing of what I had said, he just could not allow it to pass unexamined and rendered reckless and impossible. Mgqumeni had to live forever. His words had to continue being present and active in our lives even though his body had given into the abyss of death. The continuities of him wrestling with death in his music had to keep going, even though he would no longer witness (or maybe experience) the results of the struggle. My brother could not allow anything to divorce him from witnessing and/or participating in such a rich experience.

Perhaps it was his prophetic ability that had led him to grace us with such a beautiful already mentioned album titled, SMS. He knew that at some point he will go. He was to finally breakaway from the shackles of the ontological terror visited upon black people. But does that really hold true for us who the world moves against? Us, the black oppressed, who the terrors of the world, never cease to haunt and terrorize even post the event of death. He had defeated a battle on earth but another awaited him after "life" (life experienced within the parameters and shadows of death). As his contemporaries sang in unison at his funeral, a song in which he had been featured by a group called Izintombi Zika Mjaphani which says, "baphekezela mina" (they are accompanying me); one can easily think of how the song is symbolic of pressing an enabling button, kind of a 'go brother, go fight your battle, our collective battle in the other side of this life and death' thing.

As they accompanied him, it was not really an end, rather a beginning of something new even though as new as it was, not all of us could understand or read into it. Mgqumeni's music continue to be part of the great arsenal we possess as we go about trying to understand this world, the world that crashes against us, the least of these. His music enables us to see beyond our physical visuals, to override our imaginations that had been locked by our (unreal) realities. Mark Fisher calls it “capitalist realism” in his attempt to push us to think of other realities than the one that places capitalism as the only viable system for this world. This forces us to think possible of what had been ruled out as impossible.

This is so because his music speaks into the “lives” of those whose “life” is unimagined, never kept track of, unless you willing to visit that abyss, that abyss of black suffering, where “words don’t go” less they come back tainted, the lived experience of the black oppressed. Sailing against the grain, Mgqumeni’s artistic beauty and commitment in keeping track of the life of those he sang for and with, he called into gathering and fellowship, while keeping in touch with the ground allows him to come to the political ground armored as it surround those who “…live in the world, but exist outside of civil society” . Those who are constant victims of Slavoj Zizek’s crashing train that seems like a light at the end of the tunnel, a new dawn but is nothing yet another train crashing on them. His commitment and consistency in making and producing music that speaks to social responsibility, holding those holding power accountable, calling them to see and hear those who the contemporary politics has rendered without a voice, without a need to see, standing against the growing level of indifference towards the catastrophes visited upon the poor and oppressed, or fighting the “willingness not to see” can be taken and appreciated as a response to a calling, an acceptance to a task given. Fred Moten continues to speak in his sermon that “[t]his gathering in call and response, is what we practice, and what we share”

Noteworthy is a song titled Intuthuko, in this song you can find that it exists as a form of an interplay with a song that he had titled, Woza Nkululeko in another of his classic albums. In the former he speaks of societal ills, the plight of underdevelopment, the socio-economic catastrophe that is visited upon black people while in the latter, he speaks or rather gives a call, an invitation to those in high offices, leadership, particularly, political leadership. It can be taken as a call to gather, a generous invitation to fellowship. But seeing the continuities of the suffering, one can rather conclude that his call to gather and fellowship was never accepted rather given a middle finger by those who hold power (political, economic, etc). At this point one can thus argue that Mgqumeni’s music gave voice to those who their voice was not heard, not given attention too. His music cut through the fog and empowered many to say things they were afraid and less courageous to say.

It would be great disservice to speak, or attempt to speak about Mgqumeni without bringing to the fore those who he spoke with, sang and danced with, ran along with while searching and when he found his voice. Mtshengiseni Gcwensa, better known to his fans as Indidane, comes to the picture as a great musician who ran along Mgqumeni. We can call many to the picture, Ali Mgube, Thokozani Langa, Shwi Nomtekhala, Bhekumuzi Luthuli, Izingane Zoma, Imithente and many others who took place in the field at the same time that Mgqumeni was rocking his guitar in the field, putting voice into those guitar strings, as can be recalled from his song from the album Secret, when he sang “esami isiginxi siyakhuluma, sixoxa indaba nje uyizwe” which can be translated to “my guitar speaks a story that you can hear”.

We can at this point, hope that he rests in power. That his music continues to play a vital role in influencing many to learn who they are and what they do. That can only be made possible through answering a call to gather, an invitation to fellowship. It is in answering that call that we can all come together and figure it out. The end.

1 Trinity Church Wall Street, 2020. Sunday Sermon: Dr. Fred Moten. [video] Available at:

https://youtu.be/VevV9xeUNc [Accessed on 03 November 2021]

2 Mqgumeni, whose real name is Khulekani Kwakhe Khumalo is a late musician who sang music that is ascribed to the genre of Maskandi. He was from the Nquthu area in KwaZulu Natal. His music continues to roar in many spaces, this is possible because of the mark he made whenever he took that microphone and held those guitar strings. He held them hostage, made them dance to his command and split out words that shook the world and said things which had been rendered not to be said before. His voice, called into attention for all to listen when it roared, breathed fire that moved mountains and touched hearts and souls of many who listened to his music.

3 Real Talk SA, 2016. Ncedisa Mpemnyama on Artists and Political Responsibility Part 1 of 3. [video]

Available at: https://youtu.be/zdvT83MMgLcc [Accessed on 03 November 2021]

4> Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. Winchester: Zero Books.

5 Wilderson, FB, III. (2003) Gramsci’s Black Marx: Whither the Slave in Civil Society. Social Identities 9/2 (June): 225-40.

6 John Hope Franklin Center, 2018. Left of Black with Fred Moten. [video] Available at: https://youtu.be/fFTkoZTFd1k [Accessed on 03 November 2021]

7 Trinity Church Wall Street, 2020. Sunday Sermon: Dr. Fred Moten. [video] Available at:

https://youtu.be/VevV9xeUNc [Accessed on 03 November 2021]