There are events unfolding in South Africa which we can see from our windows and then there are the tensions we do not see. We hope that social scientists, investigative journalists and resourced governmental and non-governmental organisations will assist in uncovering these hidden narratives. Most importantly, we hope that media networks will share this information widely, regardless of who first uncovers it.

If each organisation, social scientist and journalist had to release information on their own platform, we would need to engage thousands of media outlets. So, a media platform (or media house) communicates the findings, reports and investigations of the people we rely on to look deeper into what is happening and give us the answers that we cannot see for ourselves.

However, the most dominant voices in corporate media concentrate almost entirely on the seen; chasing conversations that are already visible and making analysis that onlookers can already observe. For instance, during activities of protest or unrest, it is common for corporate journalists to take images of damaged storefronts and other property, or the torching of tyres, vehicles and buildings. These have come to occupy a social image of unrest, focused mostly on the relationship people have to commercial property.

Currently, the dominant narrative of the protests unfolding in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal is on the theft of items from businesses, especially large malls and shopping centres. Social media is awash of mask-clad people carrying television sets, maize meal, shoes and other consumer items—even medicines and sex toys (gasp!). No item carried by protesters (who are called looters) escapes the gaze of the reporter looking for an easy fix. The narrative has been set. The national consciousness is focused. The truth is lost in the horrors of burned buildings and raided storefronts.

Not only does this kind of reporting communicate to people that our investigative priority should be related to the economic consequences of unrest (on people who have capital), it also primes a perspective among people in society that unrest is about the destruction of property. At least, it makes the destruction of property seem like the most important event to look into. It tells us that what we need to protect most are the bricks and cement on which our social order is beholden to. It does not make people sympathetic of the struggles of people. If anything, it drives us to think of humans, just like ourselves, as deviants, criminals and “thugs”—especially when the “looters” are poor and Black.

We Need Investigation, Not Commentary

The problem goes back further than the current protests and expands farther than reporting on looting. There is a serious lack of critical investigation within South African media houses. Corporate media has endless debates, open-lines, commentators, forums, etc. But scarcely, do these conversations move past the surface. They prefer to ask open-ended questions and then broadcast people’s opinions on what they see.

This is not only the case in South Africa. For instance, during the height of the George Floyd protests in the United States, a journalist at The Intercept, Lee Fang, put out a video commentary of “Max from Oakland” who was asking why there was more attention to the killings of Black people by white people (and by institutions of whiteness, such as the police) when there are also instances of Black people killing Black people. Fang could have used his platform to share such initiatives addressing violence within Black communities or to actually answer Max’s question, through social analysis. Instead, Fang just put the video commentary out there.

This, of course, led to a polarising and hostile online environment, which is the only consequence of these on-the-surface hot takes. They don’t give us truths or help us see what is not seen. They just stir the pot, create tension and when everything settles, the truth sinks right down to the bottom and we only see again what has always skimmed on the surface. Stirring the pot is not the method to revealing what is deep within it.

Corporate media have its favourite commentators, such as Gareth Cliff in South Africa, and more increasingly has moved toward hiring people who have large social media followings to take up positions in broadcasting. It is rare for someone from the far-left of the political spectrum to be brought in to do commentary, and even then, it is not helpful.

Media corporations have sufficient resources to move past just commentary. A far-left student activist is also only engaging with what they can see, and not necessarily uncovering what is hidden. Bringing them onto a show for commentary or debate is not an investigation. In instances where people have undergone investigations into society, corporate media neglects to bring them on consistently enough to explain what they have discovered, instead choosing only to bring on social commentators who address controversial issues or confirm widely-held beliefs. It is good to bring on voices, especially regular people, to give their perspectives on social issues, but corporate media could do a lot more than this, if it wanted to.

We are in endless and fruitless discussion about socioeconomic issues, without ever submerging into analysis of root causes or solutions. Current affairs, especially when there is political turmoil, is reduced to a conversation point. The suffering of people is a purse for revenue. Corporate media leeches on our desire to understand what’s going on around us to serve us an empty hollowness of what they could discover if they only used their resources to look deeper.

Ultimately, we are left with nothing but our original opinions, further validated by images and videos of people clearing out shopping districts. We do not think if these people have food at home, how long they may have been starving, how long their frustrations have built, how often they have pleaded for relief, how they have been loyal supporters of government officials who have turned their backs on them, how they have tried to find work in an economy where there are no jobs, how so many of them have been failed over and again by oppressive systems. This is the story we do not see, the narrative which is not shared, the image which is hidden away.

Corporate Media Are No Better Than Onlookers

This kind of perspective is understandable from the people who are merely watching from their windows. They have no resources to look deeper into social events. They look out and see the fire, the shattering glass and the chants. Some are worried about whether their window might be the next to break. But, such anxieties about unrest are made even worse when well-resourced institutions spend much of their time confirming them, rather than uncovering what is not seen.

People watching unrest unfold in front of them ask, “What leads a person to put on a balaclava cloth mask and throw a brick at a shopping centre or a police car?” For the onlooker, there are no tools to answer this question, except what our eyes reveal. Some create their own narratives. But, for a resourced organisation, one wonders why they resort to using these same tools of simply onlooking, when they could investigate.

For instance, during the current protests in Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal, corporate journalists have seemed to focus (as they always do) on the destruction of property. For the 12 July edition of SAfm Sunrise, Stephen Grootes tweeted:

“There has been violence over the weekend in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng. Trucks have been set on fire and stores looted. What is the intention of this violence? What needs to happen to stop it? @SAfmSunrise #SafmSunrise”

From the day before, Nomsa Maseko posted multiple videos, images and tweeted updates focused almost entirely on the looting of stores, destruction of property and protest on streets, but at least offered some level of social analysis in a single tweet, “I guess the unemployment revolution had to be triggered by something. This may be it!”

Usually, corporate journalists only offer one-line social analysis to their large audiences. This analysis tends to just be a personal political opinion of the journalist, entirely unrelated to any investigation. For instance, Nickolaus Bauer tweeted out on 11 July, “Looting is NOT protesting #GautengShutdown”. This is just a flat political opinion with no analysis, investigation or journalism behind it.

Bauer has reduced his coverage to the equivalent of any person with no resources, who simply tweets out their personal opinions on what is unfolding. But Bauer has the resources to look deeper, to reveal what is not seen.

This is the image of corporate media, a body of political individuals with anti-poor opinions or with a lack of political will to use their resources to uncover the hidden tensions in African society. We are forced to find such analysis in the fringes of progressive media outlets, such as New Frame or GroundUp. Progressive media in South Africa is much less resourced than corporate media, but still opts to look deeper into social issues, and provide pro-poor analysis.

There have also been good examples of resourced organisations revealing these unseen tensions, such as the 2020 book, “Reflections of South African Student Leaders” produced for the Council for Higher Education (CHE) by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) or a series titled “Democratic Marxism” produced by the Wits University Press, covering multiple national and international themes, such as the ecological crisis and global finance. A media initiative, called The Continent, has also been largely invested in uncovering stories across the African continent.

The same cannot be said for corporate media. They occupy the position of well-resourced onlookers, broadcasting what we already see, but they rarely use their resources to ask why—to look deeper than the lens of their expensive cameras.

Towards A Progressive Media

Still, what progressive media often produces is more related to context/analysis pieces by onlookers, who have pro-poor opinions. We are not resourced, but we are trying our best to give pro-poor perspectives. This analysis is most often present here in Culture Review, in Africa Is A Country, in Amandla! and on occasion in between the pages of the Mail & Guardian, IOL or even the Daily Maverick.

Sometimes, we send in our articles and thoughts to the only publications that will publish them, notably to places like Daily Vox, Thought Leader (by the Mail & Guardian), News24 Voices or IOL. Those with greater networks in progressive media might find themselves in the main columns of the Mail & Guardian, Africa Is A Country, New Frame, The Continent or Daily Maverick’s Opinionista. But, much of these articles are just our opinions, sometimes backed up by our experiences.

It is not on the level of deep investigations into our society, elevating such reports from what an onlooker experiences. A serious progressive media would be providing resources for such in-depth investigations, some of which we have seen from Africa Check, Bhekisisa, amaBhungane, New Frame and GroundUp. But, still, there is much room for more progressive media and for deeper investigations.

Furthermore, even for the run-of-the-mill social analysis, it is concerning that many writers choose not to submit think-pieces to strictly progressive media organisations, choosing instead to publish in outlets like Daily Maverick. It does not help progressive media when progressive writers ignore, neglect or refuse to submit articles to progressive media, while continuing to send in written work to corporate media. This only strengthens corporate media, leaving progressive media weak.

If we are to work toward progressive media, we must build it. Unlike corporate media, progressive media does not necessarily receive funding from large donors and oligarchs. By centering itself in pro-poor narratives, it shuts out financial support from the very people it writes against—and the people that it writes for, have no money to support it.

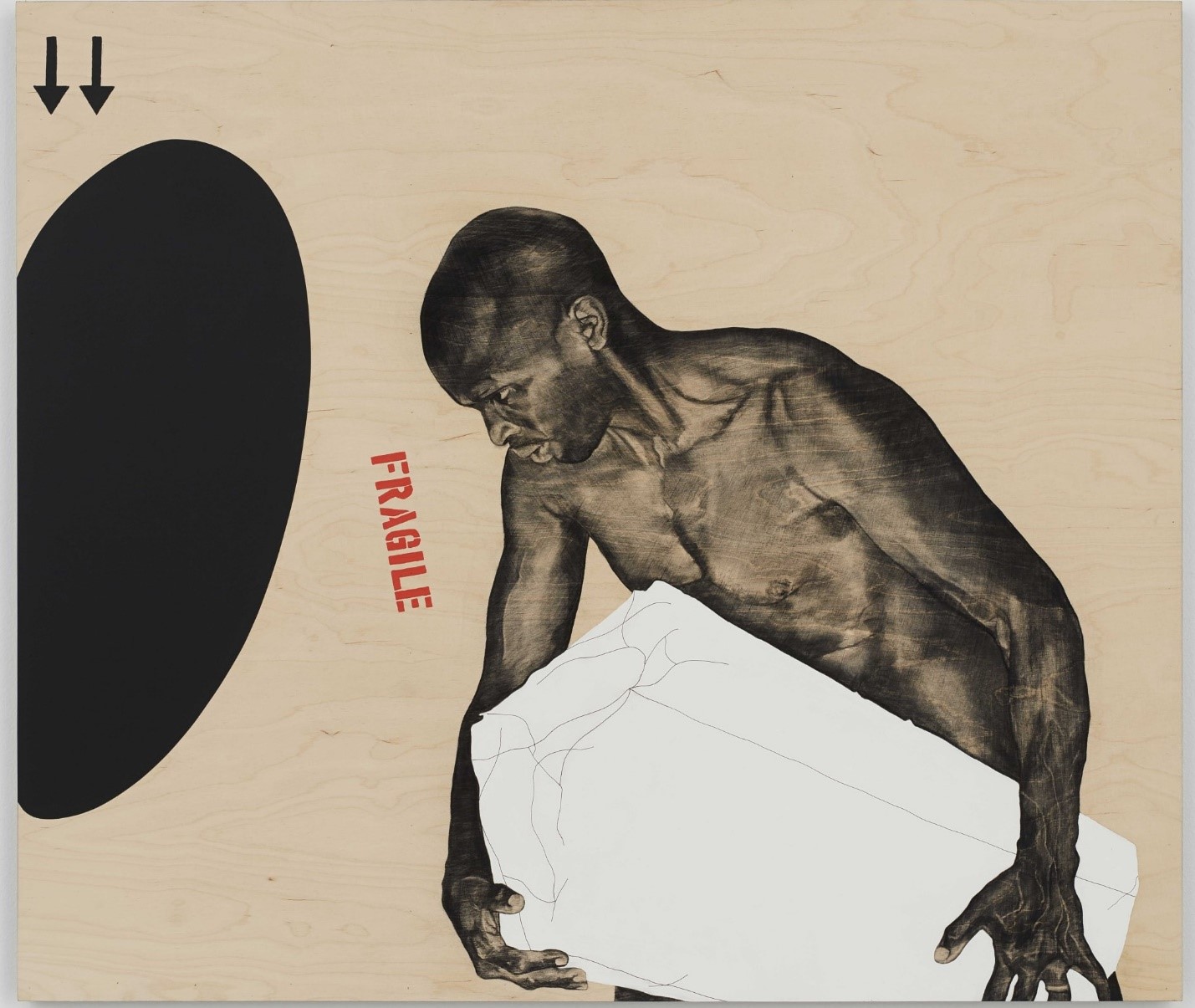

This is the dilemma of progressive media, solved only by the wilful participation of progressive activists, educators, thinkers and writers. It is we who must investigate, write and offer pro-people perspectives into the fray. It is we who must emerge from the other side of the lens holding the invisible in our hands and shining a light over its figure to make it seen. So that, when people ask why this country is the way that it is, they receive answers which are more than what they see. Revealed to them is what was before a shadow, a silhouette of the truth, a deeper understanding of their world.