A historical anti-apartheid newspaper captures the story of the defeat of the Pedi Kingdom, then under the leadership of the great Sekhukhune. The writer captures how, after Sekhukhune refused to submit to the rulership of the British, they retaliated with force; only to be crushed by Pedi regiments. Sir Garnet Wolseley, a British Field Marshal, returned after a few months to make his demands to Sekhukhune – only to realise the mammoth task before him; the Pedi were unwavering and determined. But Wolseley still wanted to take his chances. He resorted to approaching the Swazi for reinforcements, and with some reluctance on the part of Swazi rulers, they sent 8000 warriors to join the campaign. It is with the assistance of the Swazi that the British secured their victory against Sekhukhune, with the Swazi launching a surprise attack from behind the Pedi forces; whilst the Pedi were focused on defending themselves against the British troops. What stands out in this battle is that, while it is recorded that between 500 and 600 Swazi warriors died in this campaign, only 13 White soldiers were killed. And yet the victory belonged solely to the British. Although the Swazi attacked from behind, they were the bodies that met the violence head on, and provided a buffer for the British. Sir Garnet Wolseley’s gamble had payed off.

A century and a half later, South Africa finds itself in the midst of yet another battle, one against a global Covid-19 pandemic (which has claimed the lives of almost 350 000 people world-wide, infecting close on five and a half million, and counting), according to the World Health Organisation. And yet again, like Sir Garnet Wolseley, two white men, John Steenhuisen and Gareth Cliff, want to take their chances by dispensing the bodies of poor Black South Africans to the front lines.

To give a bit of background, in the midst of the global havoc wreaked by the Covid-19 pandemic, different countries have adopted various approaches in trying to curb the spread of the virus, and South Africa is no different. The World Health Organisation has lauded South Africa’s government for leading the nation’s Covid-19 response. Dr Zweli Mkhize has drawn in organised business, labour, research institutes and academics – to develop the nation’s strategy. Most South Africans applaud him for this approach, replicated across the nation’s nine provinces. The Minister’s consensus-building and evidence-based approach guides the National Command Council and Cabinet’s decisions on the regulations. Government has afforded citizens and civil society groups opportunities to submit comments and written submissions on the regulations. South Africans have indeed used this opportunity to point out weaknesses and strengths in our Covid-19 response strategy. This tradition must be upheld throughout the different phases of the lockdown because it is essential for building legitimacy. Citizens should follow regulations because they trust that government is implementing adequate measures for addressing the ongoing Covid-19 crisis. Coercion and legal, punitive measures are not sufficient for gaining broad consensus amongst South Africans, in addressing this public health and socio-economic crisis.

But the responsibility for building broad consensus must not fall on government alone. Opposition parties, trade unions, private sector organisations and non-governmental organisations must also overlook narrow sectarian interests. The recent statements from the leadership of the Democratic Alliance and its civil society supporters (especially business formations) undermine this objective. There are several signs which illustrate that these organisations are prioritising their particular constituencies’ narrow interests, over broader national public health and socio-economic concerns.

The first sign is an erroneous proposition, which separates public health from economic development or livelihood issues. The DA, and some sections of organised business, argue that South Africans must choose between public health interventions and socio-economic ramifications. This approach is not based on any empirical evidence, and ignores contemporary research on pandemics. Several research publications, like MISTRA’s Epidemics and the Health of African Nations, prove that epidemics cannot be treated as separate public health issues – outside of structural political economy considerations. In other words: there is no Chinese wall between Covid-19 public health responses and economic livelihoods. The two are inextricably connected!

The second problem with this approach is the class bias, and its emphasis on affluent class (mostly white) socio-economic and political interests. Steenhuisen, Cliff and others argue that public health concerns are overstated, and that it is possible to deal with health prevention or treatment through individual actions. State regulation of public health is characterised as draconian, even drawing comparisons with apartheid. This view clearly ignores persistent race and class inequalities in South Africa’s health system. The General Household Survey (2018) reveals that only 16% of South Africans have access to medical aid. This membership is dominated by white citizens (72%) while only 10% of Africans have access to private health care. Evidence from different experts highlights how our health systems, in both private and public sectors, require additional capacity – in order to meet sharply rising Covid-19 heath demands. So, state coordination and regulation are essential for the Covid-19 public health response. The extreme emphasis on individual freedoms, which is a core component of South Africa’s classicist liberal doctrine, is not helpful in this instance. It privileges individual and private interest groups’ socio-economic desires, over maintaining public health and decreasing socio-economic inequalities.

The race and class inequality biases are also prevalent in what these citizens perceive as immediate priorities. Tobacco (consumption and trading), access to Woolworths cooked food, and other personal civil liberties are presented as more important than addressing the nation’s collective public health challenges. We use the term ‘Woolies Revolutionaries’ to characterise this obsession with individual class-biased rights, without consideration for public health and socio-economic inequalities. This is astonishing, when one considers the steady rise in Covid-19 infections and deaths, especially in the DA-led Western Cape. Recent surveys conducted by Ipsos and the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) illustrate that most South Africans support the government’s Covid-19 regulations. Citizens are primarily concerned about access to food, health, and other basic necessities. These citizens support the proposals articulated by various civil society groups – calling for a Basic Income Grant, expansionary fiscal policies, and support for informal economy traders. Most South Africans adhere to the regulations, and there is no evidence to suggest that government is routinely committing ‘crimes against humanity’. The DA’s attempts to project its sectarian political interests, which are embedded in class and race privileges, needs to be tested against this empirical evidence.

The overwhelming support cited in these studies is not accepted without some level of criticism. Several complaints have been raised about policy inconsistencies, abusive policing, and limited access to basic necessities in some cases. This has led to government amending regulations, so as to accommodate demands from organised civil society groups and citizens. The recent criticisms levelled against government, however, over Woolies Revolutionaries’ concerns, must be read within a broader sociological context. These detractors represent privileged social and economic interest groups in our society, which create false dichotomies between health and economic livelihoods. They do not represent the view held by most South Africans, especially those from working class backgrounds, captured in the empirical studies undertaken by Ipsos and HSRC. There are some fault lines in government’s response, but it is incorrect to suggest that these constitute a crime against humanity. Government must not concede to class-based sectarian interests, which represent the views articulated by privileged elites.

John Steenhuisen’s arrogant demand that the President end the lockdown or “South Africans will end it for you”, accompanied by Gareth Cliff’s “you have to start letting our people go Mr President” – are indicative of a certain privilege that allows them to position themselves as the totality of humanity. Both figures have attempted to justify their demands by citing a declining economy, which (they argue) will mostly affect poor Black people. They have also argued that the lockdown was only meant to “buy the government time”; to prepare hospital facilities and build capacity to deal with the inevitable spike in cases of Covid-19 infection and death. Ironically, while they acknowledge that Covid-19 infections will result in some loss of life, it is the loss of lives through poverty and hunger that they claim to be mostly concerned with. Their proposed solution is that the lockdown be lifted – so that people are able to back to work, and get the economic machine running again. This proposed model is one similar to the one adopted by Sweden. The ultimate aim of this approach is to build herd immunity by letting the process play out; the more people contract the Covid-19 and recover from it, the quicker herd immunity is achieved.

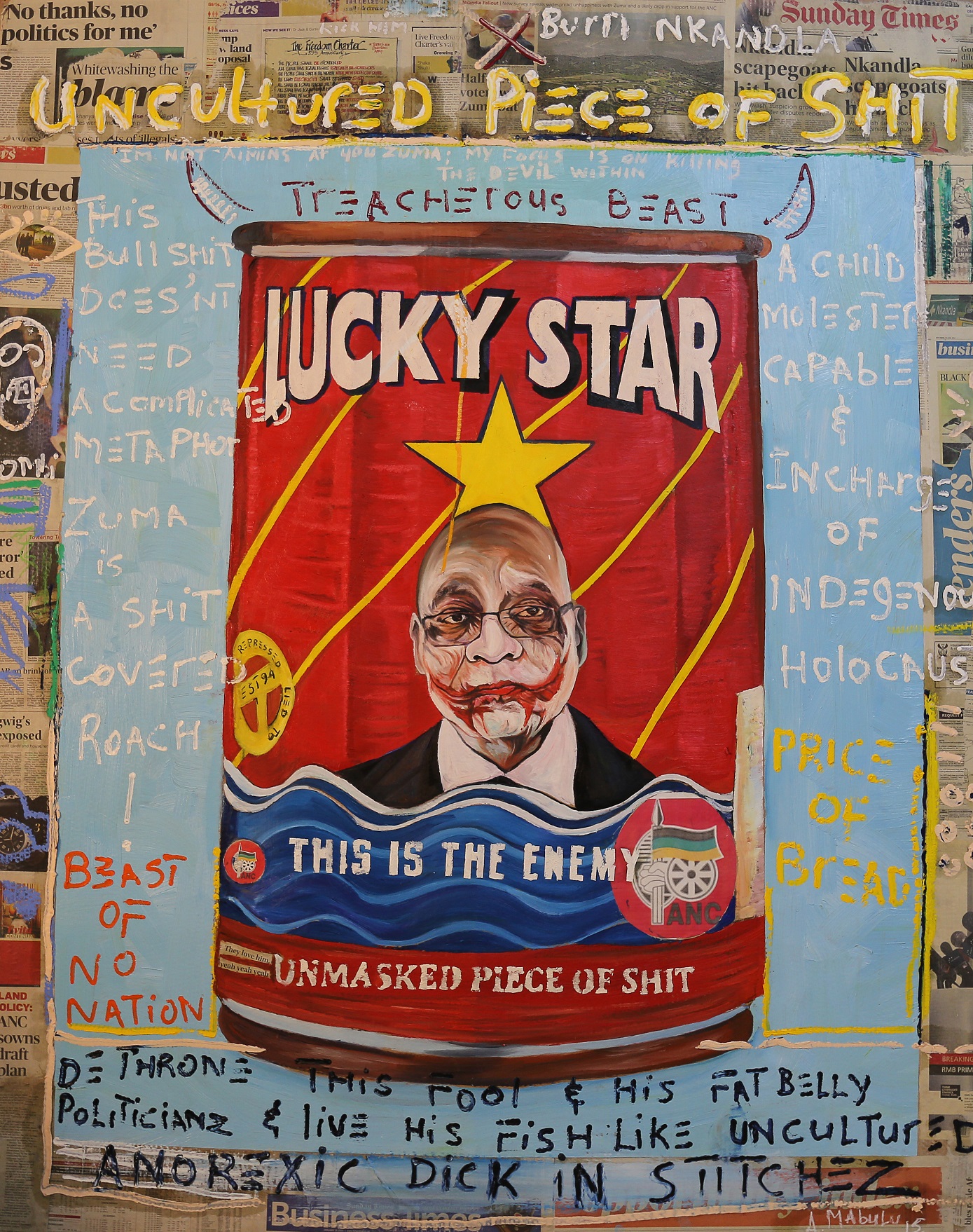

This is not the first time in history that white liberals attempt to assume the role of, as Steve Biko would put it, self-appointed trusteeship of Black interests. In fact, it was because of this very paternalist tendency that Biko admonished the liberal establishment, warning them to stop speaking for Black people – and to rather turn their efforts to those who do the oppressing of Black people. Biko’s view reflects what many Black critics have highlighted, concerning the statements of both Gareth Cliff and John Steenhuisen – there is no collective “we” that white liberals can speak of. They cannot claim to be speaking for the poor Black masses of our people, because their positionality renders them incapable of doing so. Throughout their entire tantrum about the need to open up the economy for the poor, not once do they engage the question of why it is that the people who are affected most adversely by the lockdown happen to be Black. This reflection would present them with an opportunity to unpack the workings of racial capitalism, and highlight their own complicity in the suffering of the Black poor.

We therefore liken John Steenhuisen and Gareth Cliff to Sir Garnet Wolseley because, like him, they want to win a Covid-19 battle by putting the bodies of poor Black people on the firing line. According to Professor Collin Furness, who is an infection control epidemiologist from the University of Toronto, Sweden was able to implement a no-lockdown approach based on a number of factors. Crucially, Sweden has a mostly healthy population, and does not have overcrowding. More importantly, the Swedish do not have multi-generations living under the same roof, meaning that they are able to ensure that the most vulnerable of the population; like the elderly, are able to continue to self-isolate. This is the complete opposite scenario for the majority of the Black poor in South Africa – who rely on overcrowded trains and taxis to travel to work, and return to small dwellings that house multiple generations, including the old and frail. These are also the people who do jobs that rely on physical contact and cannot ‘work from home’, as will be the case for many of the Woolies revolutionaries who want the lockdown to end. Ultimately, herd immunity will be achieved by taking this ‘herd’ to the slaughter. Although Gareth Cliff would have us believe that we will all be taking our chances by ending the lockdown, he knows that some chances are slimmer than others, and that his chances are increased by the holy hedge of White privilege which surrounds him. This Darwinist impulse towards a ‘survival of the fittest’ logic, has at its heart the well-being of the market, and not the people it purports to care for. We need an approach that centres the human being, all human beings, as its driving force.