The often-untold side of South Africa’s civilizing mission and evangelization revolves around the clash between the Western notion of civilization and paganism, particularly indigenous spiritual practices (witchcraft). This concerns how successive governments in places such as the Cape of Good Hope, Transvaal, Zululand, and Natal attempted to address the practice of witchcraft and similar practices.

Mainstream histories tend to focus on how Westerners suppressed and eradicated indigenous belief systems and cultures. However, these narratives often overlook the recognition by Western colonial authorities of both the existence and malevolence of witchcraft. They also fail to discuss how South Africa’s indigenous populations have always been intertwined with the civilizational project, a practice that persists today.

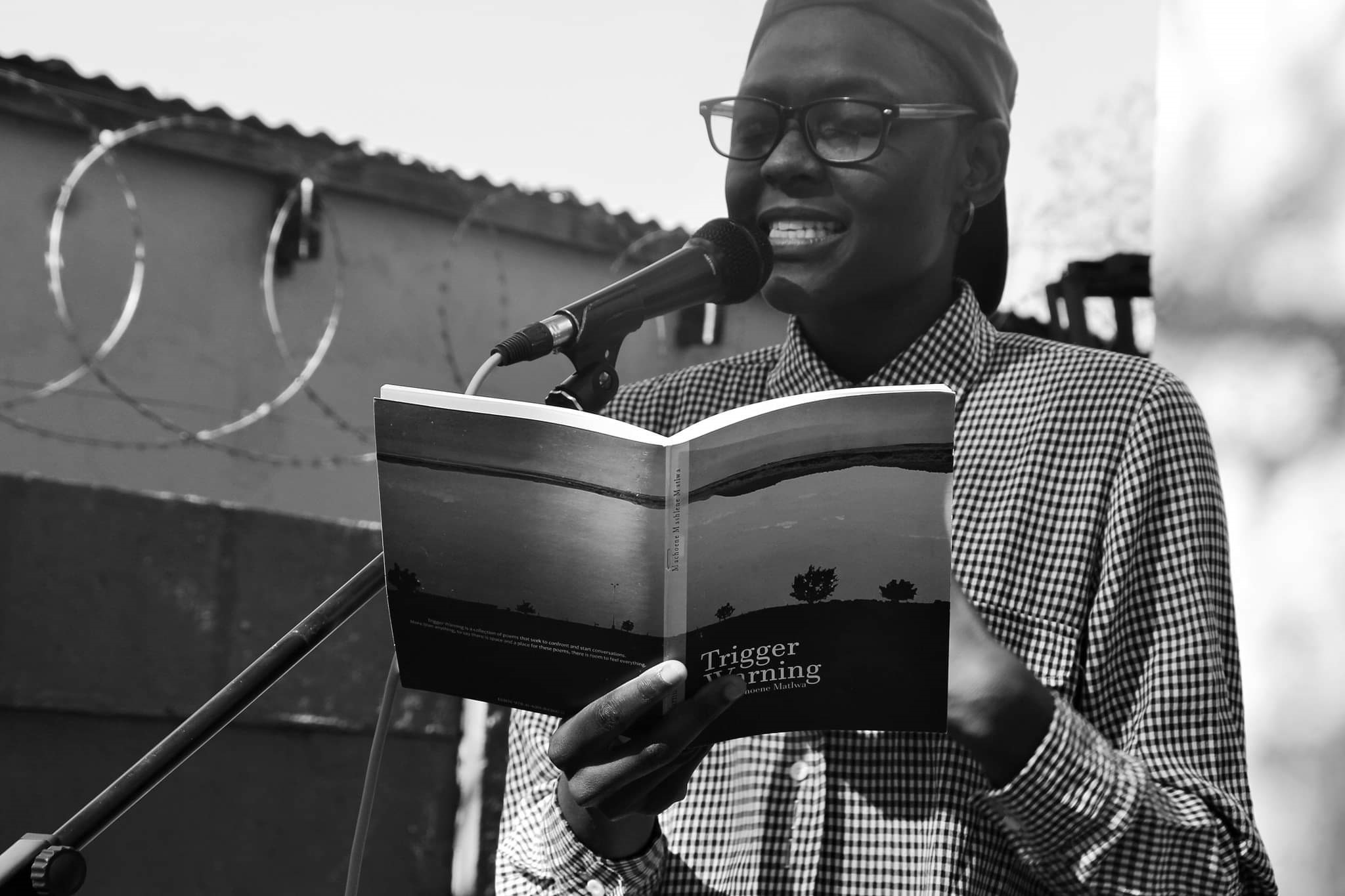

On his Facebook page, Zingisa Mavuso claims that “forty years ago, very few Black families practised amasiko (traditional beliefs), particularly in townships. The dominant vibe was Christianity.” The popularity of sangomas and izinyanga in recent years seems to contradict this historical trend and presents a complex occurrence that can be interpreted in more ways than one.

This article draws on history to address the phenomenon of forgetting, particularly regarding the enduring binary divisions of ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ as initially conceived within the Western civilizational model. It also covers the blindside of the narrative of forced assimilation to demonstrate the complex reality of indigenous populations actively engaging with and adapting to the civilizing project, a process that continues even today.

Scholars such as Mahmood Mamdani, Walter Rodney, and Bernadette Atuahene have consistently argued that land dispossession inflicted lasting psychological scars and dismantled communities. These psychological scars represent the ‘soft elements of conquest’ that do not receive sufficient coverage by scholars from different disciplines due to their complexity and gravity.

While the impact of the colonial civilization project plausibly left pain, grief, and deprivation, its victims have continued to use it as their main point of reference to navigate the black-and-white spaces. The picture is much more complicated than just a contest between the ‘civilized’ and the ‘uncivilized’. However, history concerning the civilization project is characterized by a spiral trajectory, repeating itself while introducing new layers of complexity with each iteration.

This spiral analogy helps explain the compatibility of contradictions in South Africa’s black society, manifesting in discernible repetitions that occur across time and space, shaping the art of forgetting and the continuous accumulation of layers of confusion. The reason for this occurrence is that everyone quickly forgets the saying that ‘history repeats itself’ but in different shapes and forms.

The Legal Recognition of the Practice of Witchcraft and Similar Practices in South Africa

Various laws were enacted to curb the practice of witchcraft and similar practices, including the Cape of Good Hope’s Chapters XI: Witchcraft and Other Superstitious Practices in the 1886 Black Territories’ Penal Code and the 1895 Witchcraft Suppression Act; Transvaal's Regulations 9 and 10 of the 1904 Crimes Ordinance; Zululand’s Regulations 9 and 10 of Proclamation No. 11 of 1887; and Natal's Section 129 of the 1891 Black Law Code.

The latest law to be passed in this regard was the Witchcraft Suppression Act of 1957 (amended in 1970 and still in effect). Its purpose is “to provide for the suppression of the practice of witchcraft and similar practices.” It outlines various offences related to witchcraft, such as attributing supernatural causes to illnesses or injuries, professing supernatural powers, and engaging witch doctors for gain. This would include individuals like Gogo Maweni and Dr. Mabalengwe in today's landscape.

The Witchcraft Suppression Act also prescribed many penalties, ranging from fines to imprisonment, with even harsher punishments for offences leading to death or committed by habitual practitioners. Broadly speaking, these various pieces of legislation can be interpreted as an acknowledgement by the Western colonial authorities that they recognized both the existence of witchcraft and its association with harmful acts.

Legend has it that modern Afrikaner leaders like J.G. Strijdom and H.F. Verwoerd sought Khotso Sethuntsa, a near-legendary inyanga from Lusikisiki, for his medicines for political power. Verwoerd reportedly visited him just before the 1948 elections, and many attributed the Nationalists’ victory to Khotso’s alleged medicine. Felicity Wood and Michael Lewis chronicled Khotso’s life story in the biography The Extraordinary Khotso: Millionaire Medicine Man From Lusikisiki (2018). This captivating narrative delves into Khotso’s enigmatic personality, surrounded by mystique and rumours of supernatural abilities. It is speculated that Khotso may have escaped prosecution under the Witchcraft Suppression Act due to his reputation as an unparalleled healer.

Although the Witchcraft Suppression Act is in effect, courts are not equipped to convict people of an offence whose material element cannot be presented as hard evidence in a court of law. Prosecutors avoid such cases, leading to defendants being released due to insufficient proof. Belief in witchcraft is recognized as a mitigating factor in cases of murder, assault, and arson, allowing some defendants to exploit this belief for leniency.

African Beliefs and Modern Life

Witchcraft and related practices exist in the same continuum as other indigenous belief systems that are extremely difficult to understand. Even with all their haziness, indigenous beliefs have always been used to divide, include, and sometimes discard others, a feature likely influenced by colonial civilization and biblical models. These models created binaries of civilized versus uncivilized, believers versus non-believers, and the eminent versus outcasts. Many centuries later, the black-and-white interpretation of life and social occurrences dominates thinking in black society. Today, ‘witches’ and ‘snitches’ rank among the most detested words in the black South African lexicon.

Civilization, often used interchangeably with enlightenment, typically refers to a process through which colonized peoples are encouraged or coerced to adopt the colonizing power's cultural, social, political, and economic norms. This process often involves disseminating Western ideas, values, and practices, aiming to modernize and civilize indigenous populations according to the standards of the colonizers.

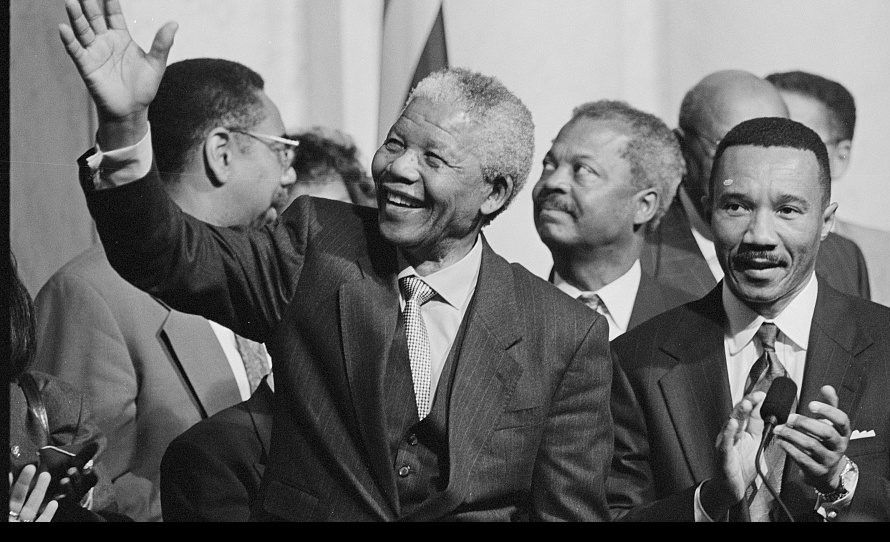

In practical terms, enlightenment was characterized by moving away from ubuqaba (backwardness) towards the embrace of isi-modern (modernism). Ubuqaba was often linked to a lack of education, adherence to traditional beliefs, and rural lifestyles. At apartheid’s peak, for example, Western churches held significant influence, benefiting figures such as clergymen like Desmond Tutu, Manase Buthelezi, Alan Boesak, Trevor Huddleston, and others.

Binary Vision and How It Influences Black Life

All of this coincided with the rural (izimpatha) vs. urban (clevers) divide, where rural individuals such as mine workers and hostel dwellers were often subjected to contempt and disdain. The emergence of Inkatha in the late 1970s to the 1990s introduced another dynamic, associating strong traditional beliefs with backwardness (ububhari).

Consequently, in townships around Durban and Pietermaritzburg (PMB), the term ‘ukulayitha’ (verb) or ‘ulayitha’ (noun), derived from enlightenment, distinguished between those perceived as progressive and those considered backward. ‘Ulayitha’ aligned with urban life and progressive forces like the ANC, PAC, and Azapo, while Inkatha members were often marginalized.

This division contributed to a low-scale civil war preceding 1994, evident in various social spheres, producing a dynamic of ‘heroes’ and ‘snitches. This situation echoes the evangelization efforts of the 1800s, albeit in different forms, with today’s landscape characterized by a divide between the educated, better-salaried black middle class and the marginalized black communities.

What is clear from this article is that colonial legacies and indigenous beliefs intersect, shaping modern black South African society and its view of life and other social phenomena. The clash between Western civilization and indigenous practices like witchcraft reflects enduring tensions and compatible contradictions. These dynamics contribute to binary divisions and ongoing struggles for identity and recognition.

Hierarchization and classism in black society not only determine who should be at the top or bottom but also who should be praised or discarded.