Many people expressed shock at what former South African international cricketer, Makhaya Ntini, revealed in his interview on SABC, about the harrowing racism that he experienced as the sole Black member of the Proteas. He achieved his 101 test matches while standing in the soul-destroying furnace of racism. Nobody thanked him for his services.

Being an honourary white in South Africa is extremely exhausting.

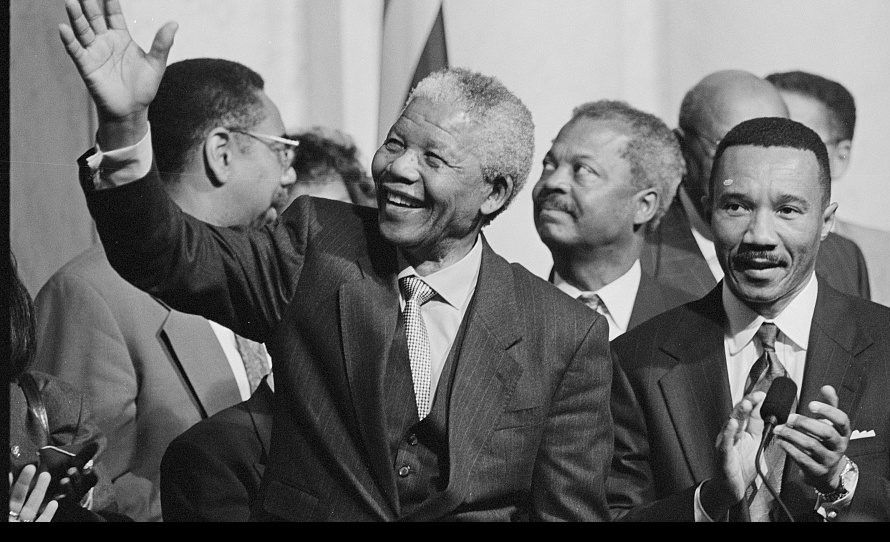

Unfortunately, there are way too many Makhayas in our midst – broken souls that were created in the early days after the ‘demise’ of apartheid. Many of us are Nelson Mandela’s sacrificial lambs, who are barbecued daily in the name of reconciliation in South Africa. These scars are still visible and very difficult to hide, yet very few people even want to know what we are going through. It is a great pity that even the young ones, cricketers like Lungisani Ngidi, cannot tell a different story.

Makhaya and I are exactly a year apart, but we never really met in person – except for one encounter at a hotel lobby in Harare, towards the end of 2017. We shared pleasantries as homeboys, but we didn’t know one another. He grew up in the Cape provinces, and me in Natal. But the racism journey we traversed is exactly the same. He was a sportsman, and I was a student at the University of Pretoria between 1994 and 1998.

Some people are asking why Makhaya didn’t speak out earlier about racism in cricket. Personally l don’t think that is the point, because there are way too many Makhaya Ntinis with broken souls across South Africa – and l am one of them. Many of them populate the much-acclaimed Black middle classes today, and others are either dead or dead poor, after they couldn’t hold on long enough to the illusion. We are distinguished members of a momentous social experiment in modern times.

Today, many of these people are approaching fifty. They keep on wondering what freedom really means after so much sacrifice – like me, they were little kids who were guinea-pigs in the making of the globally acclaimed “peaceful transition” from apartheid to the “new” South Africa. In truth, the “new” South Africa rejected us from Day Zero.

It is good that Makhaya has spoken, and everyone is prepared to listen, since he appeared on television. But the aim of this write up is to highlight one point – Makhaya Ntini represents millions in his group who were targets of sustained and painful racism, and sometimes violence, in the hands of white people in South Africa.

Democracy arrived in name only, because racism remains constant. And many people deny its existence – including the economic exclusion and poverty which point to the persistence of apartheid.

Yes, we wholeheartedly believed Mandela when he said it was time for reconciliation, and we gave our all to the project – without anyone supporting us to navigate the thick forest of Afrikanerdom – which was uncompromising, brutal and exclusionary.

The winds of change. My journey into the real, undeniably racist world of the ‘new South Africa’ started in early 1994...

Ek Is Niks Mopanie is Alles!

My Afrikaans teacher in matric recommended that l should also apply to former Afrikaans universities in Bloemfontein (UOVS), Johannesburg (RAU) and Pretoria (UP, also affectionately known as Tukkies), since they were cheaper than the former English universities like Wits, Natal and UCT. As advised, l applied to all of them. Tukkies accepted me for engineering studies, which l had to leave for commerce after less than two months in class.

A bumpy helipad. The first place of landing was the koshuis (student residence). I got a place at Mopanie, together with a Zimbabwean fellow who today is like a brother to me. First-year students (eerstejaars) were the first ones to get to the koshuis, long before the university opened. Classes started much later.

When l left home, l was told that the reason we’d to get to koshuis much earlier was that all new eertejaars were needed for “orientation” – in order to acclimatise them in their new settings.

Deur Eeenhuid Steeds Höer! This was the motto of Mopanie residence (today it is called Mopane). It was required of all new boys to wear name tags (tit-plats) and a new uniform in koshuis colours, most of the time. We would spend the entire day and night running up and down the streets like little donkeys.

We were matched with girls from Madelief koshuis, near Hatfield, and had to pick up the girls from their place in the morning; on the way to class. We’d arrive early, to perform the ritual, at about 6:30 – after walking about 3-4 kilometres from our residence.

Every evening, we’d dance and sing (for the nooitjies) Alison Moyet’s song Only You!

“Looking from a window above, it's like a story of love / Can you hear me / Came back only yesterday / I'm moving further away / Want you near me”.

The beginning of the year was fun for the white kids, who would build floats (vlotbou) and compete among one other. But before competition day, we darkies would be sent all over Pretoria, Krugersdorp, Roodepoort, Springs, Benoni, etc. – to beg for donations at intersections. I would open the sentence like this when l approached a white man with his family in their car: “Dag Oom my naam is...”

Many people were excited to see Black faces, and gave generously. But the racist ones would frown, “Voetsek klein kommunis, hierie is Pukkeland!”

We’d go to orphanages and old-age homes, where we met even more members of the Afrikaner community. Even the very psychologically confused and the senile could see a ‘kaffir’ from afar. Some of the orphanage kids wouldn’t want to play with you. And the old conservative men would state, in no uncertain terms, that they had no time for Blacks.

Generally, street adventures where we would have contact with the Afrikaner community were extremely unpleasant, and that is where you could not corroborate Mandela’s story with what you were going through. Walking as part of a students’ group – to their special places to eat or to have fun, like restaurants or stadiums – was unbearable.

We were openly abused as young Black students, by old men and women who told us in our faces that we were smelly, ugly and unwelcome.

Daag Oom Johan!

In the evenings, after dinner, it would be time for all sorts of exercises, as if we were in an army camp. Mind you, conscription had only ended in the early 1990s, so the seniors had been soldiers.

The drills were arduous and painful, but a trip to the girls’ residences or visit by the girls always brought a bit of happiness to all the boys. All this happened before the rest of the seniors arrived back from the holidays.

When they finally came, after two weeks or so, we were ready to welcome them with the greeting, “Daag Oom Johan!” (hitting our chests). They would respond, keep quiet or say “Fok-of!” As first-years we were called ‘peppies’ (still today l don’t know what this meant). The uncles were kind and caring, some took us under their wing as student mentors.

But in the main, life was difficult and racist.

Afrikaner boys looked similar and their names sounded the same: Piet, Pieter-Jan, PJ, Jacobus, Jakob, Hendrik, etc. So, we would confuse them. I’d go, “Dag Oom Johan!” (while greeting Niek). Nicer ones would respond, “Nee Peppie, my naam is nie Johan nie maar Niek. Sê dit weer.” Me, “Dag Oom Niek!” This would happen all the time.

This experience was always embarrassing, confusing and humiliating. Obviously, one would make this ‘mistake’ of mixing up their names every day.

Other ooms and fellow first-years would refuse to have anything to do with Black first-years. Some would ask: “Hoekom is julle so swart?” We were the laughing stock and true underclasses. We felt it in the residences, and we felt it in the classes.

During drills or at the dining hall, they’d refuse to stand next to you. When you were in the shower, they wouldn’t allow you to see their little ‘Parys’. Of course we’d intimidate them with our long ‘Bophuthatswana’ (only legends will understand this coding). On campus, they’d pretend not to know you, let alone sit next to you in class.

In the evenings, we’d sing for the uncles: “Alle Mopanie seniors is homosexual, Alle Mopanie seniors is homosexual!” The second years in lower floors would scream back, “Wie is ‘n mofie, julle?” Others would run to the top of the four-storey building with plastic bags full of water, which they would throw at us. “Watersakke!” they would call out loud. Then we would disperse back to our rooms to study.

In the mornings we’d be up very early, to shower and to eat breakfast. Seniors would not queue for food or laundry. But every time we met, l’d go “Dag Oom Lukas!” and bang my chest. The oom would nod in recognition and pass, especially if you said his name right and had your name tag on. The nastier ones, who were either fed up because you would never get their names right or plain racist, would shout back, “Jy’s ‘n dom, kaffertjie!” And they’d leave you bruised and licking your wounds.

The house fathers, who were meant to look after us, had little or nothing to say. Government was just too far away, and former freedom fighters were still sorting out BEE deals. We were neglected in a space that left very deep psychological scars – scars that are too deep for anyone to understand.

Afrikanerdom, Jesus, Rugby and Alles

Being at Tukkies, one came face to face with Jesus himself, who was paraded at the NGK on Duxbury Street. The deeply religious Afrikaans community cared less about the new strangers in their midst. They sang and prayed to the only God who was then forsaking them – allowing the barbaric Blacks to take over ‘their fatherland’. Perhaps, they too were not ready to see Blacks entering their little world, which they cherished so much.

Their whole world is about maintaining Afrikanerdom. Many people see Afriforum and Solidarityunïe, as well as the soon-to-be-built university in Centurion; but the Afrikaner community is inward-looking and was never going to accept the new South Africa. Blacks reconciled with themselves. The creation of the enclave of Orania was symbolic of a state of mind – a political statement and economic rebellion against the end of apartheid.

When Mandela and FW de Klerk were honoured for a peaceful settlement, the Black majority at the bottom was bruised and bloodied. The story of the transition is yet to be properly told by those who went through the devastating political violence that ravaged Black communities in the 1980s and 1990s. What happened in South Africa is akin to the US-USSR, which is always wrongly termed as a ‘Cold War’ – while millions died in proxy wars in Angola, Mozambique, Nicaragua and other parts of the world.

And life in Tukkies for me summed up the pain of young people who were left to be mauled and traumatised by racism, while the rest of the world watched their screens to witness the first democratic elections. Though many of us were still young, we knew deep down that this was not the beginning of anything new or spectacular. We decided to focus on our books, which (in all honesty), we barely could comprehend. We just wanted to pass and get out of these places that showed us the true meaning of hatred.

In front of the cameras, we were portrayed as the new picture of the new South Africa, but we were bleeding inside. In the same way, Makhaya’s teammates gave him high fives at Lords when he demolished England, but when the cameras disappeared they ostracised him. The hypocrisy is beyond comprehension, and it continues to this day.

Unfortunately, little to nothing has changed in most places of education in South Africa; from crèche to university. We also abandon our kids the same way our parents left us to fight Afrikanerdom, which never had any interest in changing. Even where we are in our places of work, we are still overpowered by this well-monied, overpowering community. It is fair to say that Blacks have grown accustomed to racism and racial discrimination.

Living as young Black students during the political euphoria that was ‘the new South Africa’ was excruciatingly painful. Sickening. Living in abject poverty among the wealthy isn’t something that one would wish on one’s worst enemy. Many Black students, as they still do today, slept hungry and hopeless – due to monetary problems.

I witnessed a girl resorting to prostitution in order to survive, while others became hard-core criminals and drug addicts who lost their minds. Life was getting harder and harder with each day that passed.

Like Makhaya, who tries now to protect and stand up for his son Thando – we attempt the same, but in vain. Seeing our kids going through the same pain, is like the replay of an excruciating horror film. The emotional and psychological burden is just way too much too carry. We try to shield our kids from centuries of oppression and indignity, but the load is just too hard to carry.

We fear for our children – no one knows how young Thando Ntini will be treated, now that his father finally opened the door for all of us to speak. Racism and abuse is the default setting for our white compatriots, a game which they have played for over 400 years. That’s why my memory avoids Tukkies.

That experience was full of loneliness, anger, frustration and tears. As a seventeen-year-old, l don’t remember how many times l cried and felt like committing suicide. Or shooting a boer, only if l had a gun! And I wished l could have climbed on top of the Union Buildings to tell my story, but no one would let me in. No one would believe me.

And still, there are people who ask Makhaya Ntini, “Why didn’t you speak earlier while playing cricket?” I couldn’t leave because l had nowhere to go. I was just too poor to quit, kukude ekhaya. Life in the township or rural areas is too bleak, too hard, too rough. Essentially, this is the daily torture Black South Africans must endure to make a living.

Nonetheless, l went on to get two degrees – in a place that never embraced me. After leaving Tukkies, l did not maintain contact with any of my white residence mates.

Through an act of nature’s cruel irony, one of them became a neighbour who couldn’t even recognise me. While he and his wife were busy harassing my family, a friend and I recognised him. A few days later l decided to greet him... he was shocked. I don’t know when he left the neighbourhood. These are men who now probably lead companies and organisations in the stubbornly untransformed South Africa. Again, we act surprised.

I have never set foot at Mopanie (or Tukkies for fun) since the day l picked up my bags to join the millions toiling in the work place – another painful story of Black life in South Africa.

As l always maintain, l have nothing to do with Tukkies – but it is where I got my degrees, and met many friends who looked like me – in a place where we were not wanted.