When questions arise about the identity of AmaHlubi, particularly in KZN, they often centre on their language. In colonial Natal and Zuid-Afrika, language played a significant role in the creation of megatribes. Furthermore, state formation in Europe involved the establishment of a distinct language as a form of political identification. For example, both the unification processes of Italy and Germany were driven by nationalist movements that underscored the importance of a common language.

Apart from its political significance, language in Africa, much like in other parts of the world, also serves as a common medium of communication among diverse groups with distinct identities and cultures. Just as the Irish and Scottish maintain strong connections to their cultural identities while predominantly using English, many African communities exhibit a similar phenomenon. People who identify themselves as AmaHlubi speak languages such as isiZulu, isiXhosa, Sesotho, Sepedi, and other languages, without necessarily associating with the megatribes often linked to these languages.

Why do AmaHlubi speak other people's languages? What happened to their own language, if they had one? Many communities, including the Tembe, Matebele a Leboa, AmaBhaca, Mapulana, and BaKholokoe, also fall into this category of nations whose languages are constantly questioned. While missionaries occasionally relied on African knowledge systems to categorize differences between indigenous languages, the overall process led to the development of new perspectives on language, particularly concerning identity (the megatribe phenomenon).

This article challenges the mainstream Eurocentric historiography that promotes a mythical Shaka and his exploits. Several scholars, including Shula Marks, Carolyn Hamilton, and John Wright, have provided compelling evidence that the creation of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka in the early 1800s did not result in the universal assimilation of the various conquered peoples into one Zulu ethnicity. Therefore, a new perspective is necessary to comprehensively explain historical occurrences, including language and identity.

In the early twentieth century, missionary ethnographers, philologists, and linguists believed that all local languages in Natal, including the speech patterns of the Hlubi communities, were "spoken variations" of the standardized Zulu language. Conversely, in the Cape, including among the Hlubi, these vernaculars were considered variations of the standardized Xhosa language. Classified as a 'tekela language,' isiHlubi shared similarities with isiSwati, Sesotho, and other Nguni languages. Very few people speak it today in its pure form after a century or so.

Linguistic theory adheres to the notion of an inherent connection between language and nationality. As a result, missionaries concluded that these standardized languages offered a more precise representation of the Zulu and Xhosa 'nations' than any of the existing identity discourses. This led to the mislabeling of all Black Africans in these two regions as 'Zulu' and 'Xhosa,' respectively. This perspective explains why German missionary Jens N. Hansen, after seven years of service in Natal, referred to his Hlubi followers in 1870 as "hard, cold, extremely indifferent Zulus." Michael R. Mahoney uses the phrase 'other Zulu' to characterize these mislabeled groups, such as the Hlubi, Ngwane, and others.

The proliferation of language-based identity narratives gained momentum in the subsequent decades. A significant catalyst for this shift arose from the increasing availability of publications such as schoolbooks, dictionaries, newspapers, and books in standard Zulu and Xhosa. Notably, there was a conspicuous absence of similar materials in the isiHlubi language. This situation prompted philologist Clement M. Doke to assert in 1928 that standard Zulu and Xhosa had established themselves as the acknowledged literary languages of "Natal and Zululand" and "Kaffraria [Ciskei] and the Transkei," respectively.

Another impetus emerged from within the Black African community, where individuals began to adopt and utilize these identity narratives to serve their objectives. This phenomenon encompassed those who migrated from rural Natal and Zululand, as well as from Ciskei and Transkei, to urban centres like Johannesburg. In these cosmopolitan settings, the broader, language-centric concepts of 'Zuluness' and 'Xhosaness' became appealing to the migrants. They found strength in numbers and a sense of belonging in these language-based identities, especially in the context of intense competition for jobs and housing.

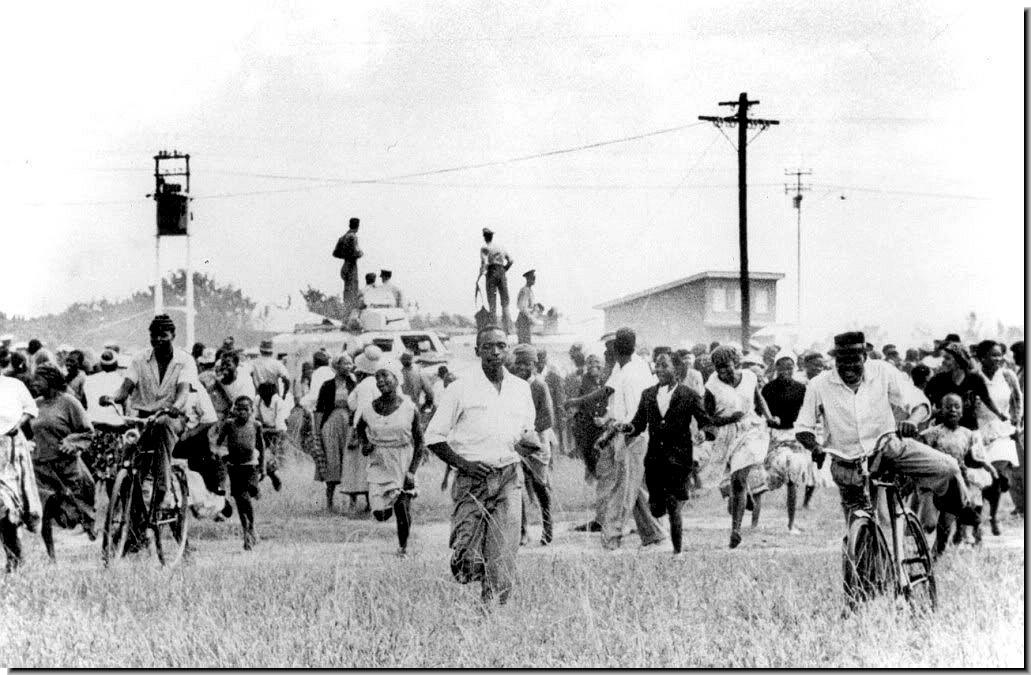

Furthermore, after the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Black Africans across these regions were confronted with racially biased laws, notably the Natives' Land Act of 1913. This legislation encouraged them to rally and resist based on these broader language-centric identity narratives. In Natal, ethnic nationalist groups such as Inkhata kaZulu (1924) and the Zulu Society (1937) actively advocated for a trans-Thukela 'Zulu' ethnic identity. This identity was based, in part, on the notion of a shared Zulu language among these communities.

Furthermore, after the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910, Black Africans across these regions were confronted with racially biased laws, notably the Natives' Land Act of 1913. This legislation encouraged them to rally and resist based on these broader language-centric identity narratives. In Natal, ethnic nationalist groups such as Inkhata kaZulu (1924) and the Zulu Society (1937) actively advocated for a trans-Thukela 'Zulu' ethnic identity. This identity was based, in part, on the notion of a shared Zulu language among these communities.

This co-optation of identity reached its peak with the enactment of the 1959 Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act and the 1970 Bantu Homeland and Citizenship Act. During this period, state ethnologists employed these language-based 'group' identities as the foundational criteria for organizing Black Africans into so-called self-governing 'nations' confined to designated homelands, often referred to as Bantustans. As part of this process, Hlubi individuals holding 'Xhosa' identity cards were officially designated as residents of the 'Xhosa' homelands, i.e., the Ciskei and Transkei, while those Hlubi bearing 'Zulu' identity cards were recognized as legal residents of the 'Zulu' homeland of KwaZulu. Since these homelands represented centres of power, their respective governments actively promoted education in the official homeland languages. In the Ciskei and Transkei, this language was Xhosa, while in KwaZulu, it was Zulu.

This persistence of language-centred identity discourses continued beyond South Africa's transition to non-racial democratic rule in the 1990s. These discourses endured because the post-apartheid state continued to recognize isiZulu and isiXhosa as the official standardized (written) languages of KZN and the Eastern Cape, respectively, and considered them as encompassing a series of subordinate dialects, including isiHlubi. The state also formulated laws and policies in line with these official languages.

This persistence of language-centred identity discourses continued beyond South Africa's transition to non-racial democratic rule in the 1990s. These discourses endured because the post-apartheid state continued to recognize isiZulu and isiXhosa as the official standardized (written) languages of KZN and the Eastern Cape, respectively, and considered them as encompassing a series of subordinate dialects, including isiHlubi. The state also formulated laws and policies in line with these official languages.

Both the state and provinces, for example, gather census data based on the presumption that South African citizens have one of these official languages as their mother tongue or first language. This compels Hlubi individuals to identify themselves as either Zulu or Xhosa speakers on census forms, thereby perpetuating the historical legacy of language-based identity classification and potentially suppressing their distinct Hlubi identity and culture. Also, legislation like the National Education Policy Act (1996) and the South African Schools Act (1996) exclusively define 'language' as the 'official languages.'

Renowned socio-linguists Robert Herbert and Richard Bailey, for instance, explain that the equation "language equals cultural group" continues to dominate post-apartheid South Africa, leading many to consider it axiomatic that all isiZulu speakers are 'Zulu' and isiXhosa speakers are 'Xhosa.' Working in both directions, this equation influences people to assume that speakers of the Zulu language inherently belong to the Zulu ethnic group, while those speaking Xhosa are automatically identified as Xhosa.

Consequently, a vast majority of young and older people may not even be aware of the existence of isiHlubi, as they primarily use the languages taught in schools. This presents an issue regarding the youth's connection to their cultural heritage. Recent efforts to revive the language are encouraging. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that the Hlubi people in the Eastern Cape are the most knowledgeable about the isiHlubi language. Therefore, they are best positioned to teach people isiHlubi in KZN and other places where the language is spoken.