When the Flame Speaks has a deep appreciation for symbolism and spirituality. Ikaye Masisi’s short film is part silent narrative fiction and part vocal documentary, interchanging between the developing story of a woman actor (Bongikwazi Ciko) in a village milieu setting and a group of various performing artists who express the role of the spirit in their work.

The use of establishment stills, the work of cinematographer Katlego Mohapi, creates a film-like feeling for the documentary subverting regular documentary storytelling. This emphasises that the short, like any film, is a narrative with setting and conflict. Stills are also used to transition the narrative back to documentary, allowing the free flow of both stories.

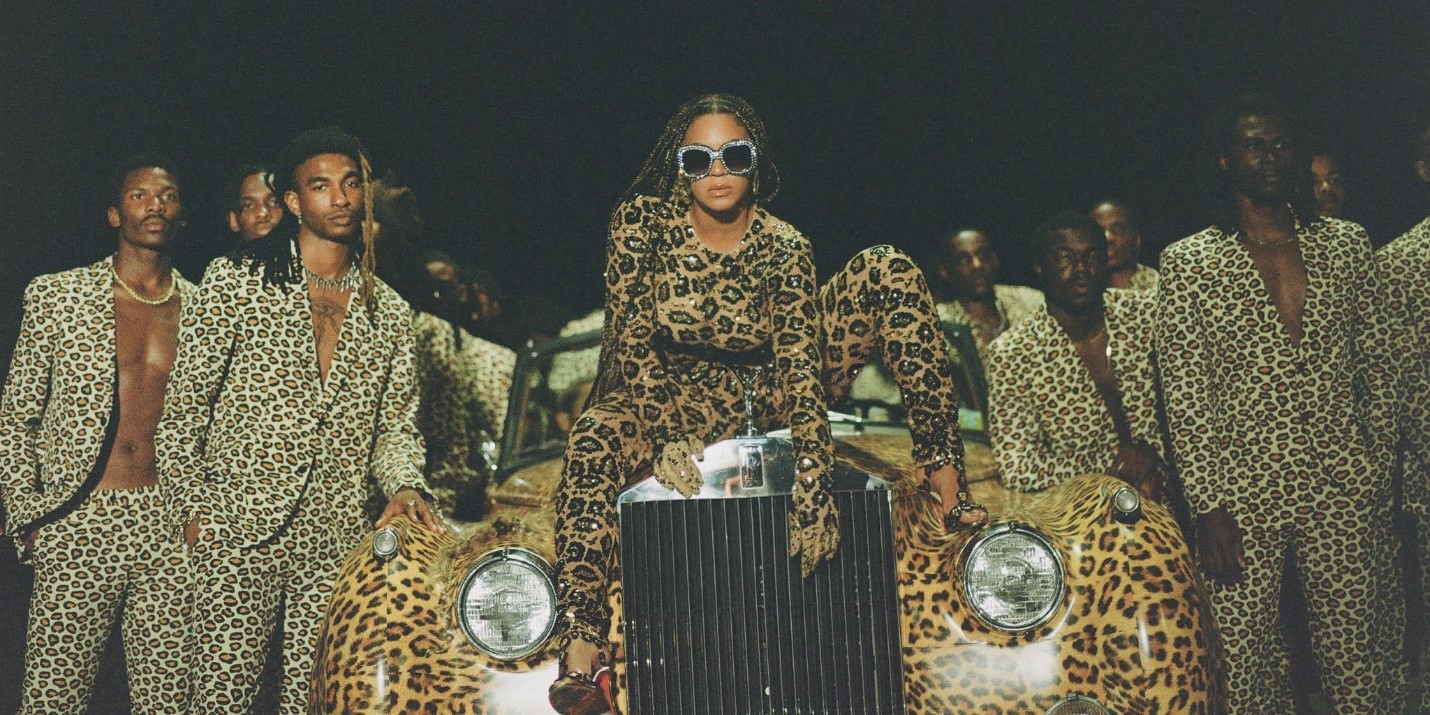

Bongikwazi Ciko in When the Flame Speaks

African Art is Immersive

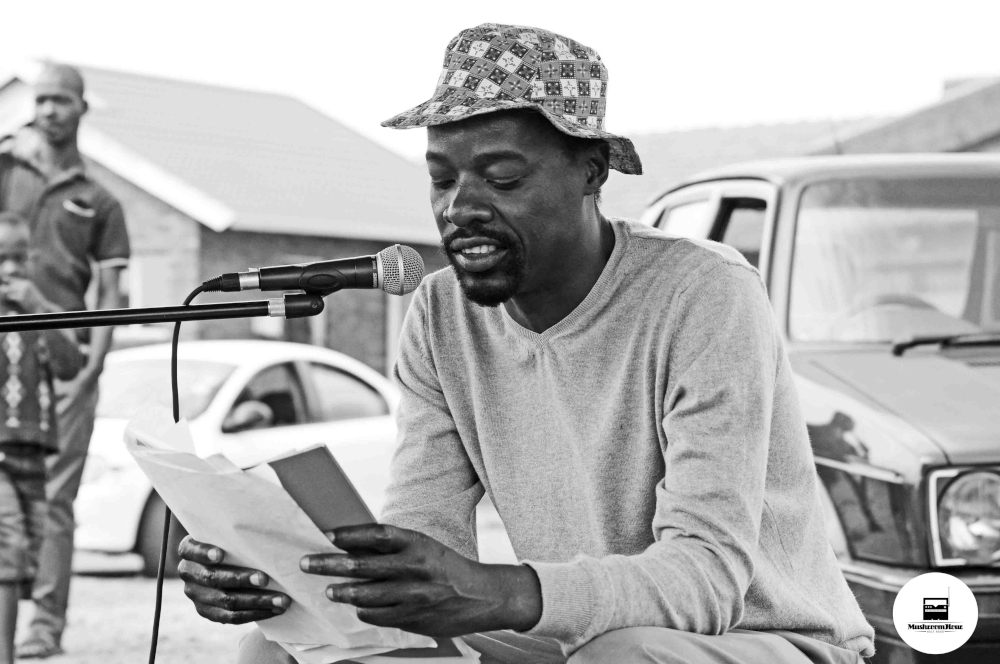

African art can be considered a deep search. The film introduces “immersive art” as a descriptive term but acknowledges that categorising African art is not always possible due to how linked our creations are to our identity and suffering. Performing artist, Nondumiso Msimanga explains that people need to shift how they understand and label art while trying to understand African art from the perspective of the artist, rather than preconception.

The norm of “killing the artist” to create a subjective understanding is subverted because removing the artist is also removing the art. Theatre practitioners, Monageng “Vice” Motshabi and Jefferson “J Bobbs” Tshabalala explain that creating art can be the shutting down of one’s consciousness and allowing the fruition of ancestral spirits or some form of heightened awareness of self. “Sometimes you sacrifice yourself,” Tshabalala warns. Our art is connected to our identity. Musician, Tumi Mogorisi claims that art is also about survival. We undergo such trauma that we have no choice but to produce.

The film gives voice to African artistic producers of audio or visual media who collectively express the consciousness of their work. By interviewing theatre practitioners, a filmmaker, a musician and various more performers, the documentary expresses how to make African art spirituality visible.

Perhaps, our art does not come from nowhere posits the film. Filmmaker, Palesa Nomanzi Shongwe expresses this as “alternate spaces that are just as ontologically true as this one”. Nomanzi explains that art allows that space to pass through them.

African Art is Struggle

The second half of the documentary covers the politics of art, which can form an institution. This system can change our thinking and become an arbiter for what art we can create. We are subject to racial capitalism and the private ownership of nature and our art. Some voices here don’t offer much in the way of a solution, apart from finding means to survive. The obstacle of power maintains.

But for some of the voices, there is the choice to produce independently and be stubborn against the system. We must through work and effort create art despite the systemic challenges. We must make arguments for ourselves, deciding our identity. This requires a rejection of art industries and a comfort within ourselves.

Provocateur Nondumiso Msimanga

A Dim Flame

The narrative itself is abstract. It is set in a few landscape areas with small human intervention where a single woman engages with various objects, both symbolic and real. For instance, mid-way into the short, there is a lit candle in the wind. The documentary invites us to just experience this engagement, without answering much about what it means. In the spirit of the flame, we should simply immerse ourselves in the art. Creative and iSangoma Vuyiswa Xeketwane states that we should listen to our bodies because they will react to works of art.

Most powerful in the fiction is a scene where the woman discovers a mask in the sand, while being observed by a hooded figure, which has been observing her. We can experience this tension and rising action, which has been preceded by the expectations of the interviews, voice-overs and earlier action in the fiction itself. But after that, we are left wanting as an audience as the fiction swiftly subsides.

Evidently, there are a few shortfalls in the documentary.

Firstly, we are asked to think from an African perspective after being told to avoid categorisation. It is unclear what an “African perspective” means outside of being conscious. There is a major struggle to define African art. It seems the documentary is not necessarily aiming to resolve this, but without doing so, the meaning of “African art” remains unanswered, while being referred to.

Secondly, the narrative remains unresolved. The fates of the woman and the hooded figure are vague. There is enough information to believe that the hooded figure is a threat, but we are not shown any resolution. It is challenging to be immersed in the narrative’s conclusion if that is not shown. This actually forces the audience to interpret an ending. If the object of the short is to shy away from interpretation toward immersion, it is difficult to achieve that when the art itself is unresolved. In some way, we imagine the ending for ourselves.

Overall, the lesson of Masisi’s film is clear. We can seek and define our art. The artist escapes their current consciousness and immerses themselves. They then invite the audience to do the same. The artist is deliberate in creating the flame and the observer should feel its warmth.