“Nothing can be changed until it is faced.” is the tagline for Tara Moore’s debut documentary, Legacy: The De-Colonized History of South Africa. So let us face the documentary, which represents a watered-down censured standardised misinformed propaganda stenography of South African history through the lens of rainbow nationist politicians and professionals.

When decolonisation must be decolonised

The documentary claims to be decolonial, but it does not actively challenge any official narratives of South African history that any scholar can find in a ninth grade South African textbook. Some examples:

1.The documentary opens with the narrative that the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) stopping at the Cape for a ‘refreshment station’ and that the voyagers renounced their European identity to become Afrikaners. We know from historical record the conquered multiple terrorities, such as Java, under the authority of the Dutch government, prior to their arrival and established of Cape Town on 6 April 1652. The Ducth government was aware of the potential to engage with “natives” and gave the VOC the authority to act with impunity to protect and monopolise the government’s trade routes. The innocent idea that the VOC just wanted a refreshment station is itself colonial history that the film parrots.

2.The documentary argues that Black people fought with the British during World War I in order to be recognised as citizens, under the presumption that being engaged in the war effort would contribute to Black emancipation in the South African colony. However, whle the ANC believed this, it is very likely that Black people fought in the South African Native Labour Corps because they offered Black people wages higher than they could earn elsewhere because they were denied from owning land or earning wages in areas that would compete with white people and in some areas, were not allowed to earn wages at all. There was

3.The documentary erases Africanist perspectives entirely, with the notable exclusion of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania from their section on apartheid resistance, including anti-pass campaigns and the Sharpeville Massacre, which is portrayed entirely as an ANC affair. From watching the documentary, one would presume that only the ANC and the multiracialism agenda opposed and participated in resistance against apartheid. The documentary makes no mention of the Freedom Charter and the subsequent split between the charterists and africanists, nor any of the ideological role of radical africanist resistance. For a decolonial project, the film conveniently excludes the very groups of people who self-proclaimed to have a decolonial agenda. The ANC, for its part, often appeal to colonial powers rather than serving an agenda to dismantle them. So it is odd fof the documentary to appeal to the ANC as the foremost decolonial organisation during the apartheid resistance.

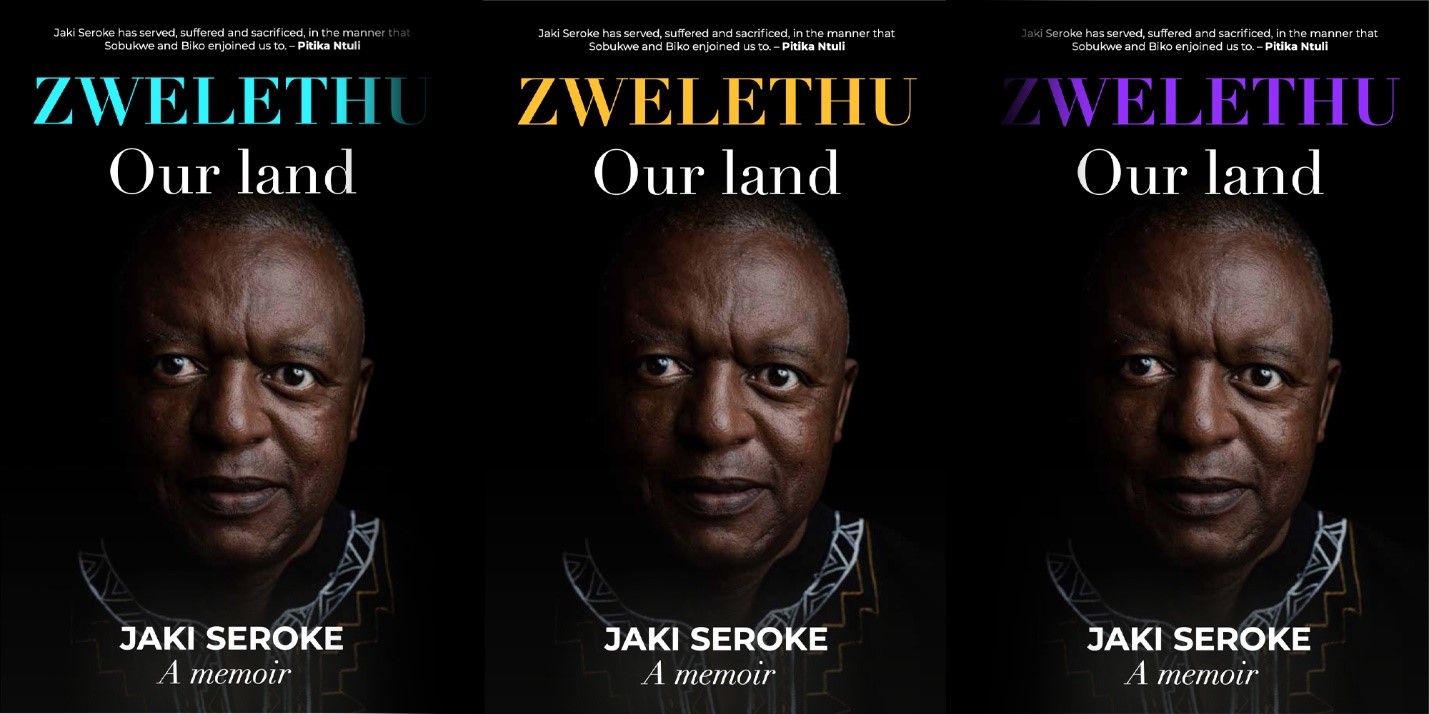

Zweledinga Pallo Jordan, who served in the ANC NEC and South African cabinet.

There are numerous more examples, since the documentary jumps from claim to claim, narrative to narrative, spanning from the 17th to 21st centuries. This surely disproves whether the documentary is a genuine historical endeavour since it priorisites broad strokes over delicate portrayalas of history, jumping from significant event to the next, rather than unpacking any of them. What is the point of a map of history that is so zoomed out that we fail to even see its borders? The documentary exhibits itself as a glossary of events, a one-sided summary that is skewed toward the country’s ruling party, including voices of that party to glorify their anti-apartheid activism. Commentators included Zweledinga Pallo Jordan, Mac Maharaj, Barbara Masekala, Jay Naidoo, Hilda Ndude, Allan Boesak, Haroon Bhorat, Albie Sachs and Wilhelm Verwoerd: a slate of state stenographers.

Nothing New, Nothing Added

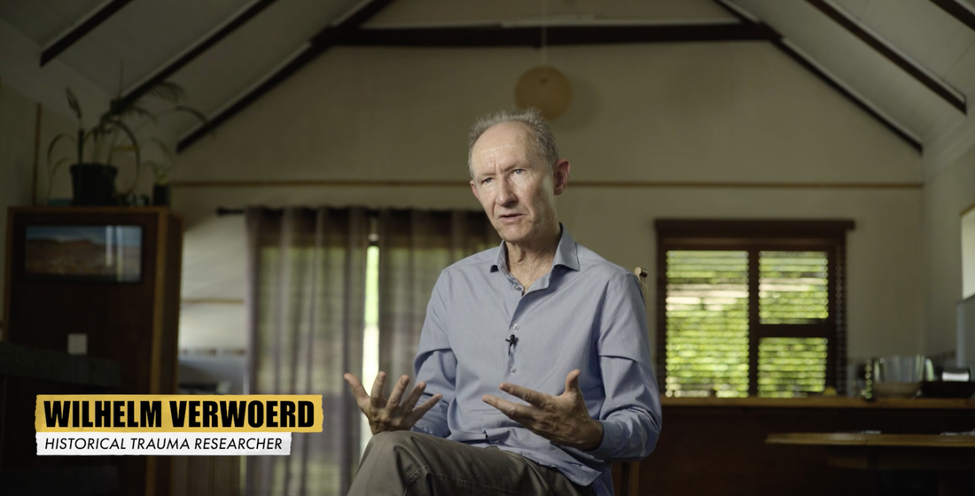

A great sin of the film is that it offers no new, unique, or interesting perspective that musters the need to produce the documentary in the first place. The one seemingly valuable aspect of the documentary is the inclusion of Wilhelm Verwoerd, the grandson of apartheid ideologue Hendrik Verwoerd. However, Wilhelm’s contributions are as typical and mundane as any standard narrative from a liberal white South African ridden by guilt from their contribution to the systemic oppression against Black South Africans, which sustains today. Wilhelm’s message is for white South African to engage in “white work” which is the acknowledgement of one’s involvement and benefit from white supremacy. And then what? Wilhelm does not say. But, we gain no insights from Wilhelm about their grandfather or about anything only they would know, which is what is supposed to warrant their inclusion in the documentary in the first place.

Wilhelm Verwoerd, the grandson of the “architect of apartheid” Hendrik Verwoerd.

Instead, the documentary is one big ‘ol argument to authority, whereby esteemed public intellectuals are invited to narrate and comment on the history of apartheid the ANC. Perhaps since such important and qualified public intellectuals say something, it is worth considering. But that is simply not the case for the reader who has any pre-existing knowledge of decolonial South African history. Instead, one will cringe at the washing away of heterodox or divergent narratives to have a unified, standardies view of the ANC’s legacy.

Perhaps, the greatest sin of the documentary was that it was too transparent in its inadequacy. It made not attempt to even pretend to muster historical intrigue. We all know that it is ANC voices speaking on ANC matters to push and ANC agenda. The film has little to do with South African history and everything to do with the you-know-whos who still indoctrinate scores of youth around the country to believe in the fallacy of the ANC History of South Africa.