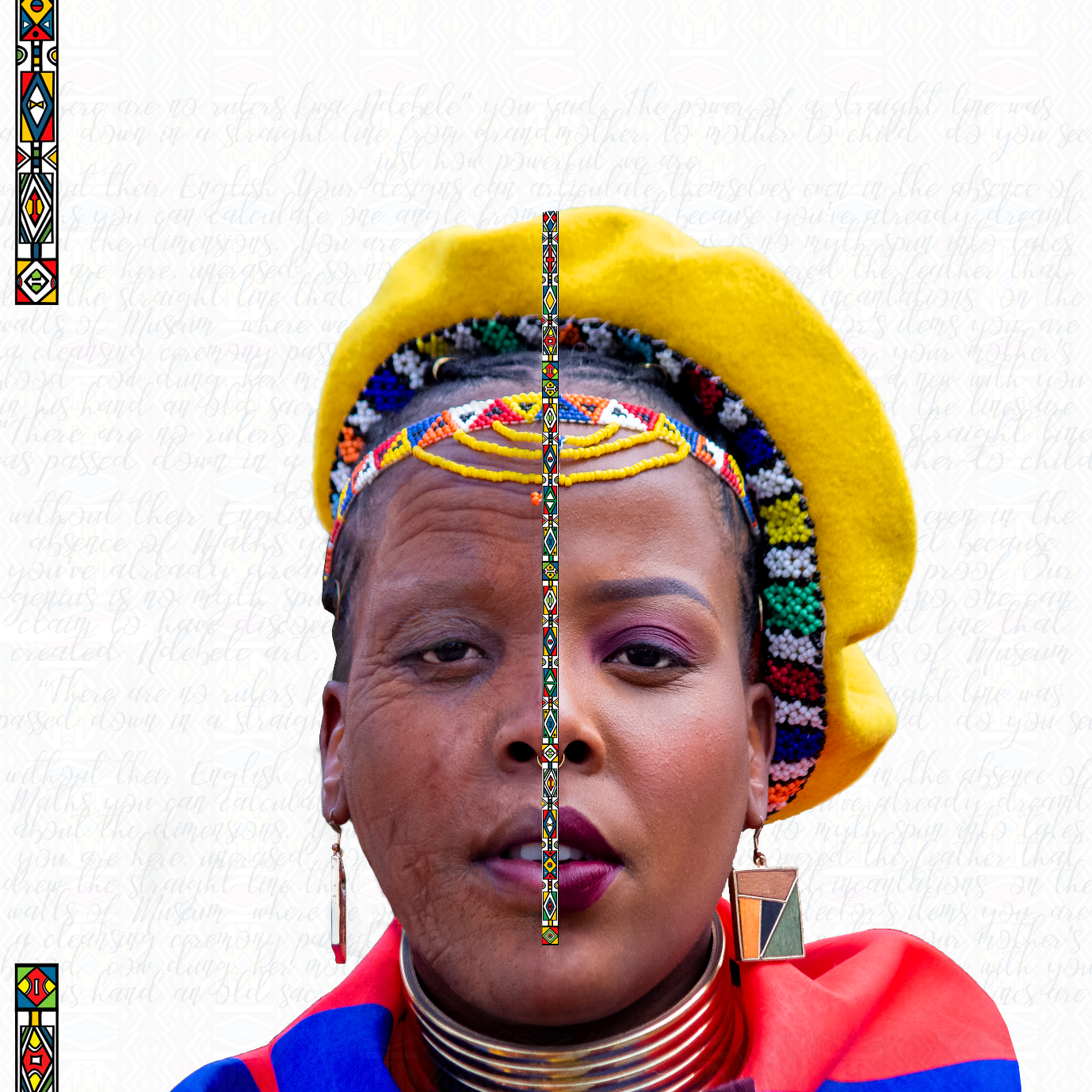

As it does every year, Heritage Day came and went. Traditional (South) African outfits and food flooded my timelines as it does every year. Everyone was “united” in their little middle-class bubbles as they usually are. Headwraps and champagne seem to make a wonderful combination, especially when matched to a designer bag or two. I will not even talk about the fictitious joke that is “Braai Day”. Fuck you white capital – you steal enough from us!

Every year, on the 24th of September, I feel least South African. Everyone around me just seems to know how to translate centuries of tradition and culture into a one day event through language, attire and food. It plays out so merrily. Everyone seems so proud and centered in a sense of belonging. By the time the sun sets, I’m still trying to figure out what to wear. Cook. Eat. Where do I belong? Tomorrow, everyone will be back at work in their “slaying” ensembles accompanied by some shallow motivational quote drenched in neo-liberalism. Where will I be? Still trying to figure it all out.

This year I find it particularly hard to let go of the traumatising experience of “celebrating” heritage as a country. My story leaves me feeling less celebratory than most.

I am told that my paternal great-great-grandfather was brought to South Africa as a Ghurka (soldiers of Nepalese nationality recruited in the British Army). I don’t know much about life during war, but in between it all, generations were birthed which included my grandfather. Here the story becomes clearer. My grandfather, classified as an Indian man, married my grandmother – a very fair coloured woman. They were married in the ‘30s and divorced by 1948. The way I understand it, it was a loveless marriage fraught with the wounds of colonialism and apartheid. You see, my grandfather was a trader and received fewer benefits as an Indian man. He married my grandmother so that he could build a case for being reclassified as a Cape Malay and hence for trading in coloured areas in Cape Town. He traded on her name in the meantime. It took him years to achieve this reclassification. The sense of inferiority and the material restrictions imposed on him were so damning, that he invested his life into attaining worthiness – however attenuated.

Throughout this time, he banned his children and himself, from speaking his mother tongue, Urdu in the home. He did this so that there would be no chance of identifying him as Indian before he was reclassified. So, my father and aunt could not learn the language and were unable to teach me and my cousins. This has been a hole in my heart for years. My grandfather’s need for personal validation and access to capital was so great that he would abandon his mother tongue for it. Can you imagine the violence of such an excision? The result: A highly dysfunctional, farcical marriage and severely damaged children, whose own children still bear the scars.

My truth about my maternal bloodline is less concealed. Malay slave heritage at the Cape mixed with coloured lineage from the Northern Cape. De Villiers and Peters are the surnames passed down from the masters. Although the truth is more obvious here, the inferiority it evoked caused it to eat itself. It was obvious as day that we were the descendants of Malay slaves and in the earlier years I remember a tendency to celebrate it through recalling the significance of the “Kaapse Klopse” and “Die Nagtroepe”. The distance between us and history seemed to grow as time went by. Interestingly, my paternal grandfather became a member of the Malay Choir Board after his reclassification. Eventually, it became shameful to remember our Malay traditions and heritage since we had already moved to the Northern Suburbs – closer to whiteness. Personally, I identify with very little of it because I grew up so far removed from it.

The slave heritage I speak of was hardly spoken of in our home. It was that shameful secret the family has buried and moved on from. It was only alluded to when unpacking the roots of our French and English surnames. It was skillfully overshadowed by the kinship to colonial saviourism (as it was sold to us). I mentioned the Northern Cape. Kimberley, to be exact. Do you think any acknowledgement of Khoikhoi or San lineage was ever given in our family? I’ll leave it there, because I still don’t know anything beyond what I speculate or hope is true.

I want to be a product of my own history, but I am not. I am a product of the distortion of it.

Today, I see people so confidently anchoring themselves to a heritage through dress, food, language, and dance.

I don’t know what to wear on heritage day. It would be inauthentic of me to dress in Malaysian style, because I am not from Malaysia (and the other Indo-Asian countries my ancestors were ripped from). Besides, whatever they brought here was violently stripped and re-presented to them. I inherited dispossession and memory-loss from them. Dressing like a Kaapse Klops feels inauthentic too because the lack of pride instilled in me still resonates in what is now a hollow, sepia memory. The lure of whiteness and assimilation stole my grandfather’s tongue from me. My slave tongue, Afrikaans, was co-opted by whiteness so that I still get funny looks when I speak Afrikaaps. Religious discord manifested through my grandmother who gave up Christianity for my grandfather but still couldn't stand the "slamse" until her dying day. What confusion! My own family distanced us from our truth, as a survival mechanism. Now I am tasked with the labour of actively remembering and denouncing the shame I was branded with. I want to be close to my heritage, but I am not. After all these struggles for freedom, I am still left behind because I am only now learning that I had lost anything to begin with. I am only now figuring out how to recover it.

Me, the free one. The one who doesn’t know what struggle is. The one who doesn’t have to fight for anything.

So, when we are celebrating our heritage, I am still learning about it. My heritage is loss, shame, betrayal, self-flagellation, denial, forgetting, mutiny, dispossession, trauma, erasure, fraud, co-optation, lovelessness, abduction, abandonment, selling-out, resistance, survival.

I am not writing myself down as a victim, but this day leaves little for me to celebrate.

For fuck’s sake; I don’t even know what to wear!

If you are reading this: I’m still figuring shit out. Sorry to keep you waiting.