“Masabata shouldn’t have died the way she did. For someone who sacrificed as much as she did and to die in an undignified way. Necklacing! That was the worst that could befall a soldier for the revolution such as her.”

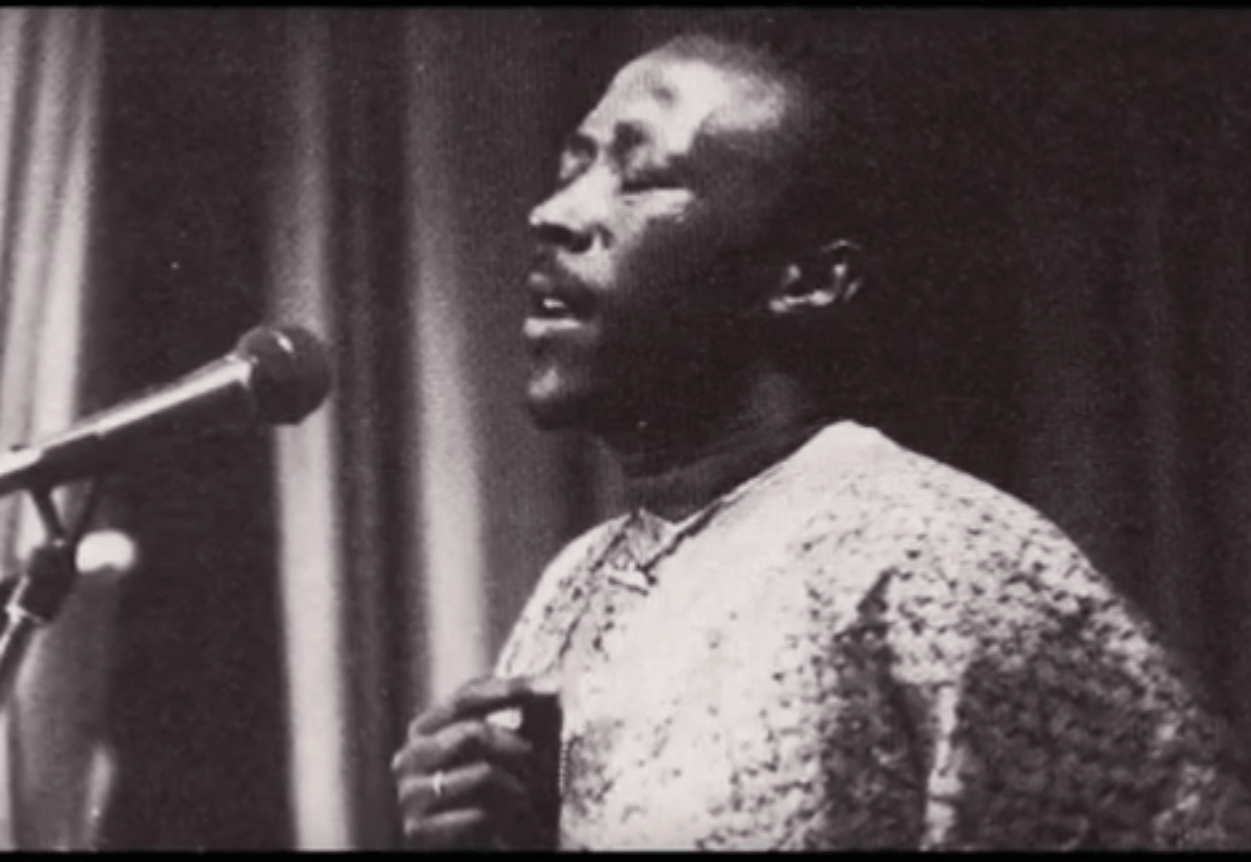

These were the sobering words of Black Consciousness veteran uBab’uThabo Ndabeni. He made this observation during a discussion with political peers this week, on the Black Student Uprising of 1976.

Bab’uNdabeni was one of the leaders of the 1976 uprising. A day or so after this discussion, I had the honour of receiving a call from him. He wanted to know if I had succeeded in my efforts to get a picture of Masabata.

I indicated that, unfortunately, I still have not found a picture of her, but have requested colleagues who are attached to various universities and research bodies, to help in the search for a picture (and more) of Masabata.

I also said to uBab’uNdabeni that it was important that we host a proper and dignified memorial for Masabata and that her story could be used to excavate the untold stories of the contribution of Black women revolutionaries, not just to the 1976 Uprising, but the Black liberation project broadly.

I then decided that as part of keeping the memory of the Black Student Uprising of 1976 alive, I will publish a revised tribute to Masabata. Later this week, I will also republish another forgotten story of the 1976 Uprising: the story of the brutal murder of young Christopher Truter of Bonteheuwel, in the Western Cape.

This year, the act of choosing to remember Masabata has been particularly emotional heavy. This is because I found myself drawing parallels between Masabata’s murder and that of two other Black women.

In my own mind, the story of Masabata is so similar to that of Makie Sikhosana and Mary Turner. Makie Sikhosana was a young COSAS activist from the former East Rand, who was brutally killed on 20 July, 1985.

Makie was brutally attacked by a mob of mainly Black boys (some who were her own comrades). She was kicked and pelted with stones. She had fragments of broken glass inserted into her private parts and was set alight. Makie was falsely accused of being an impimpi.

In May 1918, a 21-year-old Black woman, Mary Turner, was publicly hanged and killed by a bloodthirsty white mob in Georgia, in the United States of AmeriKKKa.

Like Makie, all manner of brutality was unleashed on Mary’s body. She was hung upside down, kicked, stabbed, doused with gasoline and set alight. Mary was eight months pregnant.

Mary’s crime was to beg for mercy for her husband (Hayes Turner), who had been falsely accused of killing a white slave owner. Mary and Makie were essentially lynched in public. However, in the case of Makie, she was lynched by her own kind: Black people. And this is the deeper tragedy of her story.

I first heard the name, Masabata Loate, in 1996 from the legendary poet and writer uBab’uDonatto Matter. After hearing of Masabata’s story, it stubbornly stuck to my memory.

From some of the material I have studied and a recent conversation with Black consciousness icon and liberation struggle historian, uBab’u Tiyani Lybon Mabasa, we learn that Masabata was one of the foremost leaders of Black students in the 70s.

Together with uBab’uThabo Ndabeni and others, she is the co-author of that epoch-shaping moment of Black resistance: The Soweto Student Uprising of 1976. For her involvement in the Black liberation project, the racist-settler-colonial regime sentenced Masabata to ten years’ imprisonment.

She served five years on Robben Island. It is said that upon her return from prison, she was deeply disturbed by how Black politics had regressed. She couldn’t hide her disgust with what she saw.

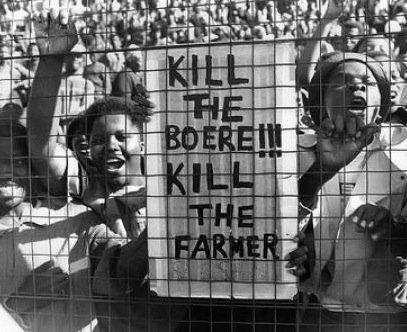

So she became openly critical of how some elements of the ‘liberation movement’ were conducting themselves. She was particularly opposed to the practice of killing fellow Black people by necklace.

In reaction to her condemnation of this vile act, she was brutally attacked by a mob of mainly young Black male 'comrades’, near her home in Soweto. They were armed with among other things, pangas and axes.

Even though she was able to escape, she was eventually cornered and met her demise right in front of her grandmother’s house. Masabata was literally hacked to death.

Like Makie and Mary, Masabata was essentially lynched. “That she had to die this way, after dedicating all her life to the cause of freedom and justice, is heart-breaking”, were her mother’s words in reaction to the brutal murder of her daughter.

At the time of her brutal murder, Masabata was only 29 years-old and a former Miss Soweto title holder. Masabata was part of a rare breed of young Black revolutionaries, who had literally dedicated their lives to the liberation of Black people.

For her selflessness and unconditional love for her people, Masabata was brutally killed. Even more painful is the realisation that, she was killed by the very people for whom she fought so gallantly and went to jail for.

The tragic circumstances of Masabata’s death bring to memory the immortal words of Danton, who during his trial in the midst of the French Revolution said “The revolution like Saturn devours its own children”.

The 17th of October this year will mark the 34th anniversary of the brutal murder of Masabata. It is my hope that the idea of a dignified memorial in her honour, as discussed with uBab’uThabo Ndabeni, will indeed happen. As painful as Masabata’s story is, it is important that her story be told over and over again.

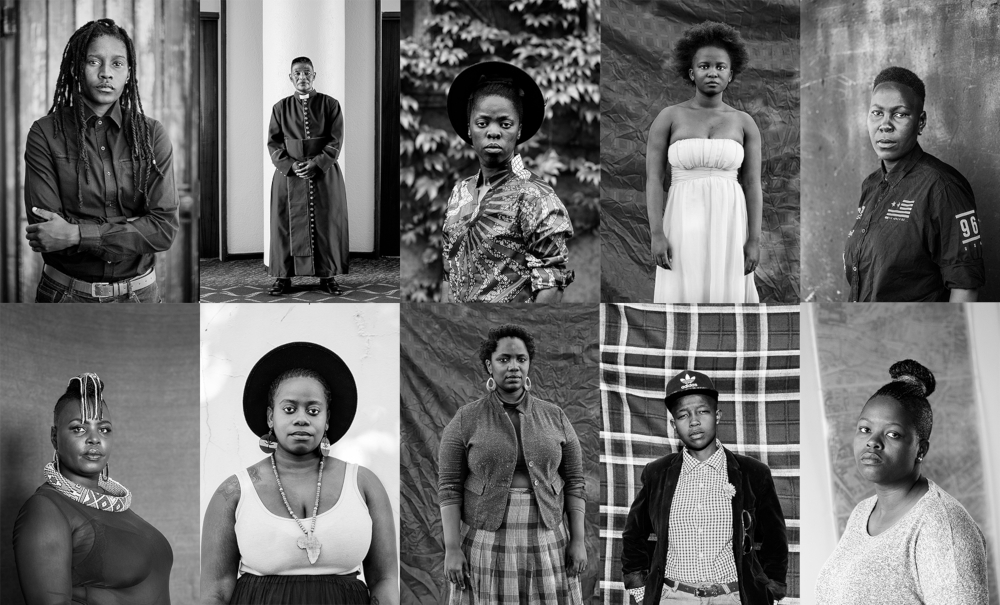

Most importantly, it is important that we make a deliberate effort to highlight Masabata’s bravery and sacrifices, and that of the many other Black women revolutionaries, whose gallant stories continue to be a footnote (where they are told) of South AfriKKKa’s overwhelmingly androcentric Black liberation narrative.

Recommended Readings

2. THE BLACK WORLD MUST NEVER FORGET MARY TURNER ,BY VELI MBELE, 22 APRIL, 2019

3. Woman Activist Slashed to Death on Soweto Street With AM-Restricted, Bjt