I commenced university in 2017, right on the heels of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign. RMF, a student movement opposing the South African colonial education system, began with protests on March 9th, 2015, primarily demanding the removal of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes, a notorious British colonial settler, from the University of Cape Town premises. As the movement expanded, its focus shifted from removing colonial structures, like statues, to the broader goal of decolonising university curricula.

I belong to the cohort of students who navigated university during a period when discussions about the decolonisation of education permeated campuses. Both students and lecturers engaged in conversations about what a decolonised education and society would entail. Interestingly, some argued for decolonisation in good faith, while others opposed it. This divergence is not surprising; universities, deemed as the ivory towers of knowledge production, are ideal sites of struggle, where diverse perspectives naturally exist due to various schools of thought influencing and shaping students' and lecturers’ outlooks. In essence, universities are supposed to be places where festivals of ideas take place.

Being a student during this period inspired me to actively participate in the discussion about decolonisation. One key point raised by the RMF movement was that decolonisation would never be complete without black intellectuals as lecturers. However, the current reality reflects a shortage of black intellectuals in South African academia, failing to mirror the country's demographics. Consequently, there is a significant underrepresentation of black people in the South African intelligentsia. The pertinent question arises: Why do we lack sufficient black intellectuals in South Africa today? Is it because the black population, constituting more than 80% of the country, lacks the necessary prowess to become intellectuals? Or is there a deliberate, systematic apparatus suppressing black intellectuals?

As a history student, when I enrolled in my Master’s program, I decided to investigate this shortage of black intellectuals today and the underrepresentation of black people in academia. Through a historical lens, I traced this phenomenon back to the apartheid regime, which segregated and subjugated black people, ensuring power and privilege for white individuals. This structural advantage for whites extended to the production of intellectuals in apartheid South Africa. Karl Marx captured this reality when he said, “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas." In apartheid South Africa, intellectual fraternity became an exclusive domain of white individuals.

Antonio Gramsci, grappling with the concept of intellectuals, argued that they are responsible for sustaining, modifying, and altering the modes of thinking and behavior of the masses. Similarly, Edward Said posited that intellectuals are individuals endowed with faculties for representing, embodying, and articulating messages to the public. However, in apartheid South Africa, intellectuals were racialized, and black intellectuals, like black people, faced discrimination based on race and harsh conditions.

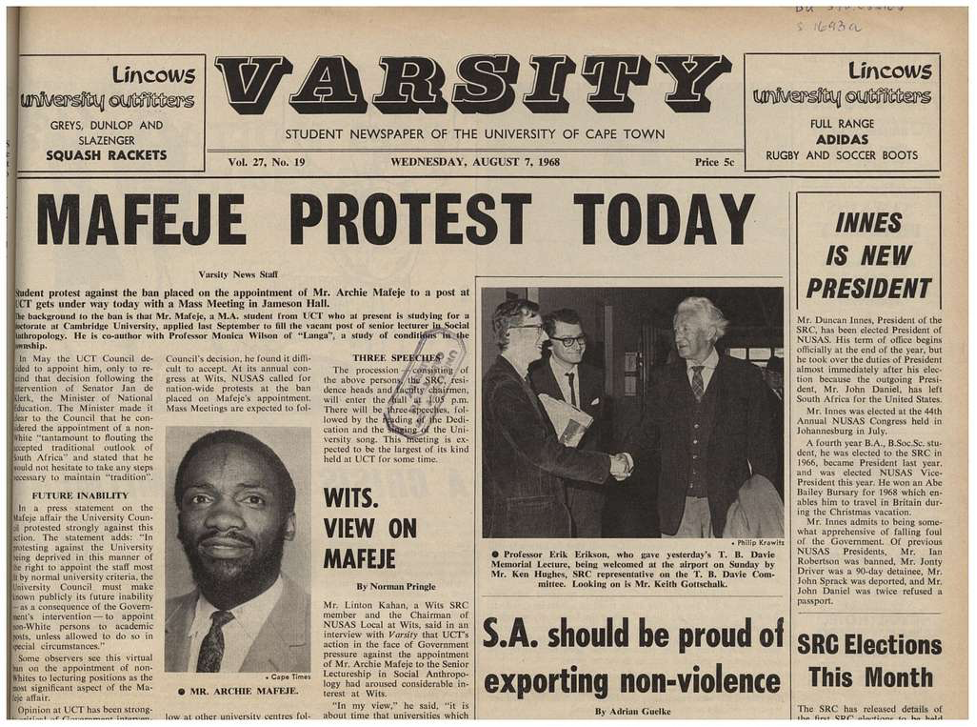

Universities, where intellectuals are typically based, played a particular role in apartheid South Africa. Louis Althusser, a Marxist sociologist, argued that institutions of learning fall under ideological state apparatuses that serve the interests of the ruling class and reproduce the status quo. This is precisely what universities did in apartheid South Africa—pledge allegiance to the regime. A notable instance is the denial of employment to a black intellectual, Archie Mafeje, as a lecturer at the University of Cape Town in 1968 based on his skin color, despite being the most suitable candidate. The decision not to employ Mafeje became a consensus between the apartheid regime and UCT.

My study on this phenomenon revealed that a significant number of black intellectuals and potential ones left the country, either to work or study abroad, as it was challenging to do so in apartheid South Africa if you were black. Many black individuals opted for exile to fulfill their intellectual aspirations. Consequently, black intellectuals spent decades in foreign countries, and South African academia remained white-dominated. Remarkable minds like Es’kia Mphahlele, Bernard Magubane, Archie Mafeje, Can Themba, Lewis Nkosi, Nat Nakasa, Mazisi Kunene, Livingstone Mqotsi, Bloke Modisane, Mzala Nxumalo, etc., could have become influential black intellectuals in South African academia had they not been silenced during apartheid. Although a few returned to post-apartheid South Africa, a substantial number of black intellectuals never came back from exile.

Some black intellectuals remained in apartheid South Africa and overcame formidable challenges. However, they are a minority, subjected to harsh racist experiences. Chabani Manganyi, for example, in his memoir titled "Apartheid and the Making of a Black Psychologist," writes about his struggle to secure employment in South African universities despite being an exceptional black intellectual who completed his PhD at the age of 30. This reinforces the argument that in apartheid South Africa, there was a deliberate effort to suppress black intellectuals.

The void created by apartheid in the production of black intellectuals in the country is still palpable today, evident in the continued underrepresentation of black individuals in the South African intelligentsia three decades post-apartheid. The overarching conclusion of my study, the argument presented in this article, is that there has been a deliberate, systematic apparatus to suppress black intellectuals in South Africa. This argument dispels racist perceptions used to justify the dearth of black intellectuals, such as the claim that black people lack the necessary prowess to become intellectuals.