The Lost Prince of the ANC: The Life and Times of Jabulani Nobleman ‘Mzala’ Nxumalo 1955–1991, written by Mandla Radebe, is a biography of one of the most dedicated anti-apartheid activists in South Africa. The book features a foreword by Dr. Blade Nzimande, who knew Mzala from their student days at the University of Zululand to their exile in London. In the foreword, Nzimande shares his personal and political experiences with Mzala, as well as his reflections on Mzala’s legacy and relevance for post-1994 South Africa.

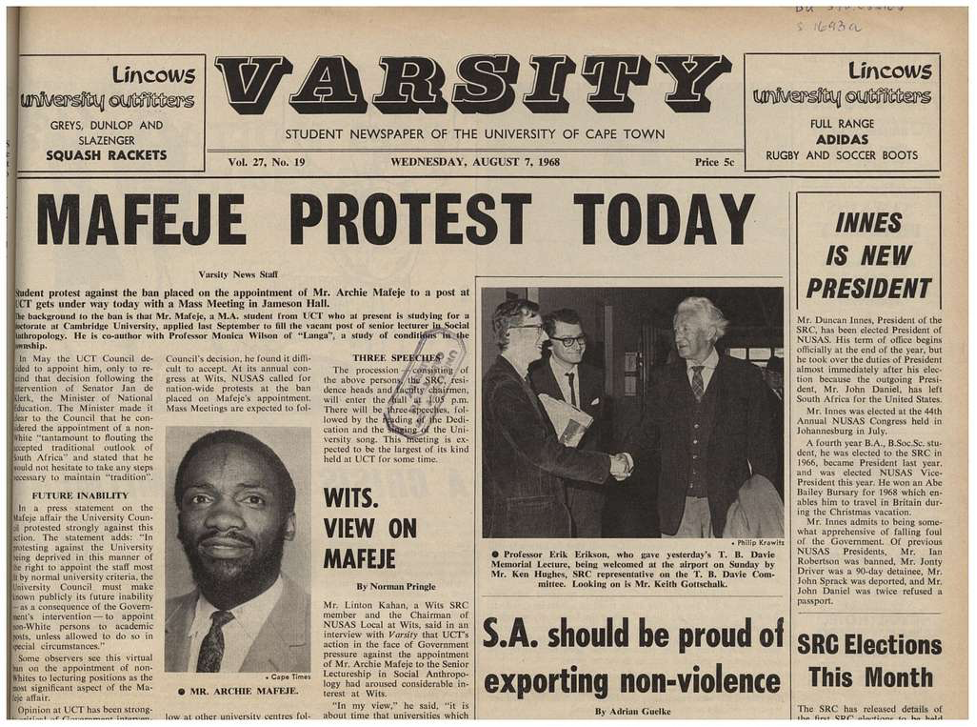

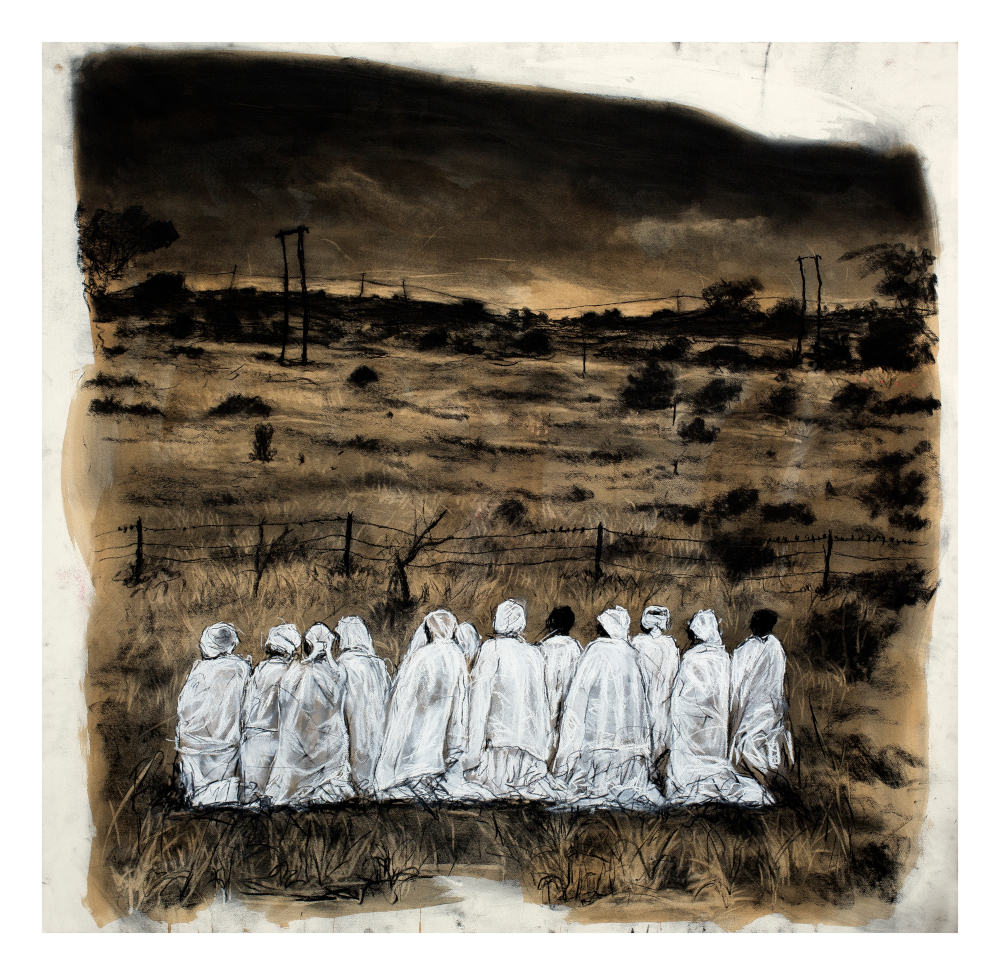

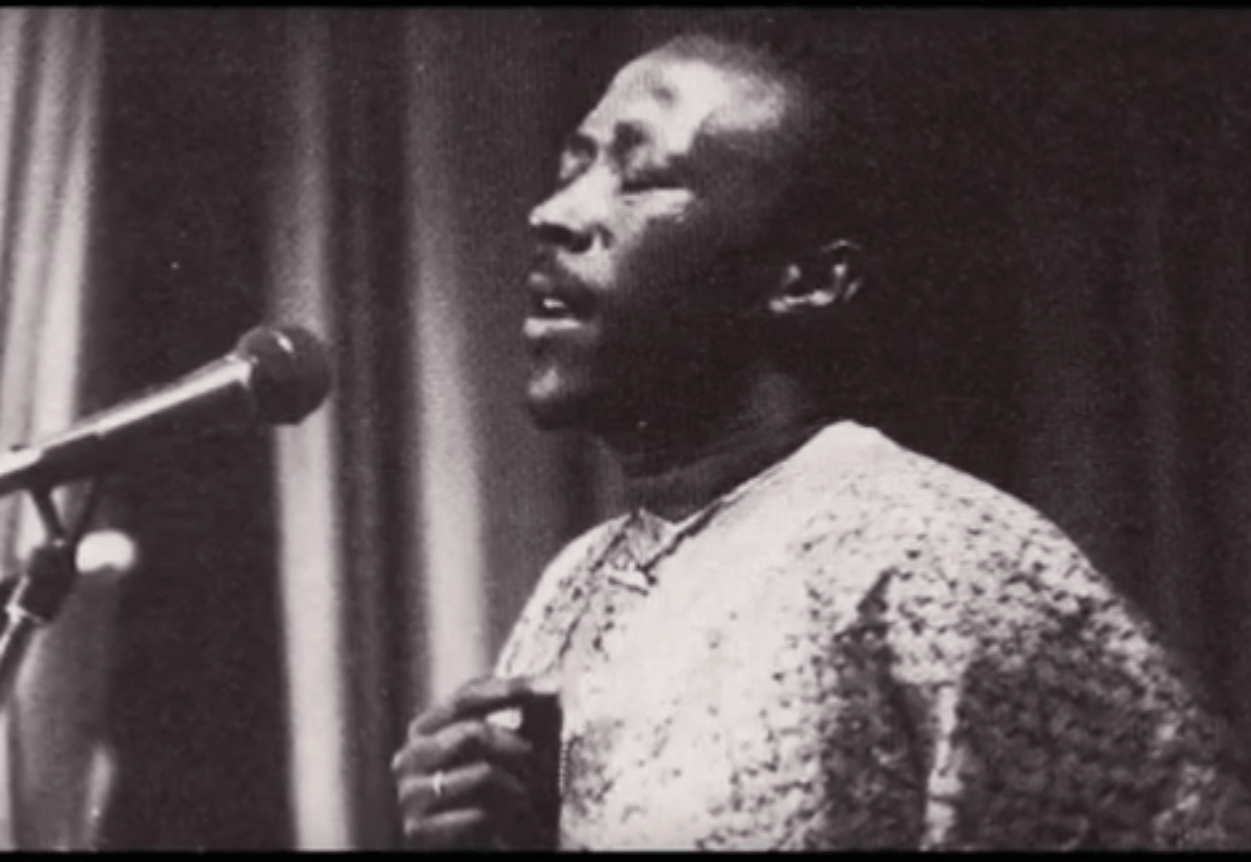

Nzimande begins by recounting how he met Mzala in 1976, when they were both first-year students at the University of Zululand. He describes Mzala as a vocal and intellectually sound individual who was very active in student politics and outspoken in student body meetings. He also reminds the reader of the historical context of that year, when the Soweto Uprising sparked a wave of protests across the country against the oppressive Bantu education system. The University of Zululand was one of the institutions that joined the uprising, leading to the disruption of the academic year and the persecution of many student activists. Mzala was among those who had to flee the country and seek refuge in exile.

Nzimande then narrates his encounter with Mzala in London in 1988, where they were both pursuing their PhDs and continuing their anti-apartheid activism. He recalls how they spent a lot of time together discussing various topics of interest, such as the role of the Inkatha Freedom Party in fomenting tribal and ethnic divisions through Zulu nationalism. He also reveals that it was Mzala who recruited him into the underground activities of the South African Communist Party, of which Mzala was a prominent member.

Nzimande also comments on the controversy that surrounded Mzala’s book on Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the leader of the Inkatha Freedom Party and a former ally of the ANC. The book, titled Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a Double Agenda, was published in 1988 and provoked a lot of debate both within and outside the ANC. Nzimande writes that some people, including Buthelezi himself, accused the book of being poorly researched and biased, while others, including academics, praised the book for being well researched and balanced. Nzimande also notes that Buthelezi tried to prevent the book from being sold and distributed in South Africa, and that the book has not received the attention it deserves.

Nzimande's argument about the post-1994 challenges and the role of the anti-apartheid generation is not only relevant for Mzala's book, but also for his own position and actions as a leader and an activist. However, it can be argued that the negotiated settlement came with a lot of shortcomings that are super-individual, systematic, and structural. Therefore, many of the elites that lead South Africa today have such good credentials that hardly match their actions today. When one compares their present-day activities with their contribution to the struggle against apartheid, one might be disappointed because of what they have become. For instance, Dr. Leigh- Ann Naidoo, a senior lecturer at the University of Cape Town, has been consistently raising concerns about the anti-apartheid activists whose roles are questionable in the post-apartheid dispensation1. In 2015, Naidoo penned an open letter to Professor Barney Pityana, who was at the time the president of the UCT convocation, condemning his silence during the Rhodes Must Fall movement against colonial education2. Pityana has rich struggle credentials as the founding member, and first Secretary General of the South African Student Organisation (SASO) who succeeded Steve Biko in the position of president in the same organisation3. It astonished and concerned Naidoo that her generation was inspired by the generation that coined and promulgated black consciousness, a generation to which Pityana belonged; however, Pityana, present at UCT during the RMF days, was silent on the decolonisation struggle that was taking place right in his own backyard2. In contrast, delivering the 15th annual Ruth First Memorial Lecture at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2016, Naidoo argued that the anti-apartheid generation has become afraid of the future4. A generation that opposed apartheid before 1994 has become a stumbling block whenever the younger generations dare to challenge the status quo, according to Naidoo. They make assertions such as ‘we are already in democracy’, ‘we have already achieved liberation’, and ‘there is no need for revolutionary action because the laws and institutions of post-apartheid are sufficient’4. Naidoo herself is part of the post-apartheid generation of activists who advocated for the decolonisation of education in 2015/6 through movements such as Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall, and the generation that fought apartheid now in positions of power and privilege, either as university management or government officials, was identified as the stumbling block for Naidoo’s generation to achieve the decolonisation of education4. Nzimande himself is one of the people who have been greatly condemned by the Fallists for hindering the attainment of free and decolonized education and reversing the gains of Rhodes Must Fall and Fees Must Fall as the Minister of Higher Education, Science, and Technology5. Thus, this part of the foreword raises important questions about the continuity and change of the anti-apartheid struggle, and the responsibility and accountability of the post-apartheid elites.

Nzimande concludes the foreword by reflecting on Mzala’s life and death, and the questions that have been raised about what he would have become if he had lived to see the end of apartheid and the dawn of democracy in South Africa. Mzala died of natural causes in 1991, three years before the first democratic elections. Nzimande expresses his frustration with such questions, as he believes they are often asked by people who are not genuinely curious, but rather by people who want to use the dead to criticize the living. He argues that these people are ahistorical, opportunistic, and reactionary, and that they ignore the complex and challenging realities that the liberation movement has faced since 1994. He says that speculating about what Mzala would have done or said is futile, and that the best way to honour his memory is to learn from his example and continue his struggle.

1: Naidoo, L. (2016). The Anti-Apartheid Generation is Afraid of the Future. [online] Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2016-08-18-ruth-first-lecture-the-anti-apartheid-generation-is-afraid-of-the-future/ [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

2: Naidoo, L. (2015). An Open Letter to Barney Pityana. [online] Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2015-04-23-an-open-letter-to-barney-pityana/ [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

3: Pityana, B. (2018). The Struggle for the Soul of a South African University: The University of Zululand, 1960-2015. Cape Town: African Minds.

4: Naidoo, L. (2016). Ruth First Memorial Lecture 2016. [video] Available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ZwQyYxW0f8 [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

5: Molefe, O. (2017). Blade Nzimande: The Fallist. [online] Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-10-18-blade-nzimande-the-fallist/ [Accessed 17 Feb. 2024].

Source(s)

1. How To Write an Engaging Book Review | Grammarly

2. 17 Book Review Examples to Help You Write the Perfect Review

3. 13 Guidelines for When to Start a New Paragraph in Your Story

4. How to Write a Three Paragraph Book Review - Pen and the Pad

5. Free Text Summarizer | Reduce Your Reading Time - Scribbr