The democratic dispensation has granted all citizens over the age of 18 the right to cast their vote for their preferred candidate or party in elections. Supposedly, this offers everyone an equal right to have a say and influence in the government of the country. This has been the case in South Africa for the last 30 years. Before 1994, this right was exclusively preserved for colonial white settlers. They were the ones who enjoyed this franchise. In 1994, change happened; black people gained this right too, after a long struggle. People were jailed, exiled, and executed. This right was never easily earned. Black people did not get it because colonial, racist, and narcissistic white people had ceased to be so; it was because of the pressure exerted by black people. The possibilities of meeting on agreeable ground between blacks and whites had to be explored. Therefore, the right for everyone to vote came as a result of unanimity after certain compromises had been made. South Africans were voting for the national government for the seventh time this May.

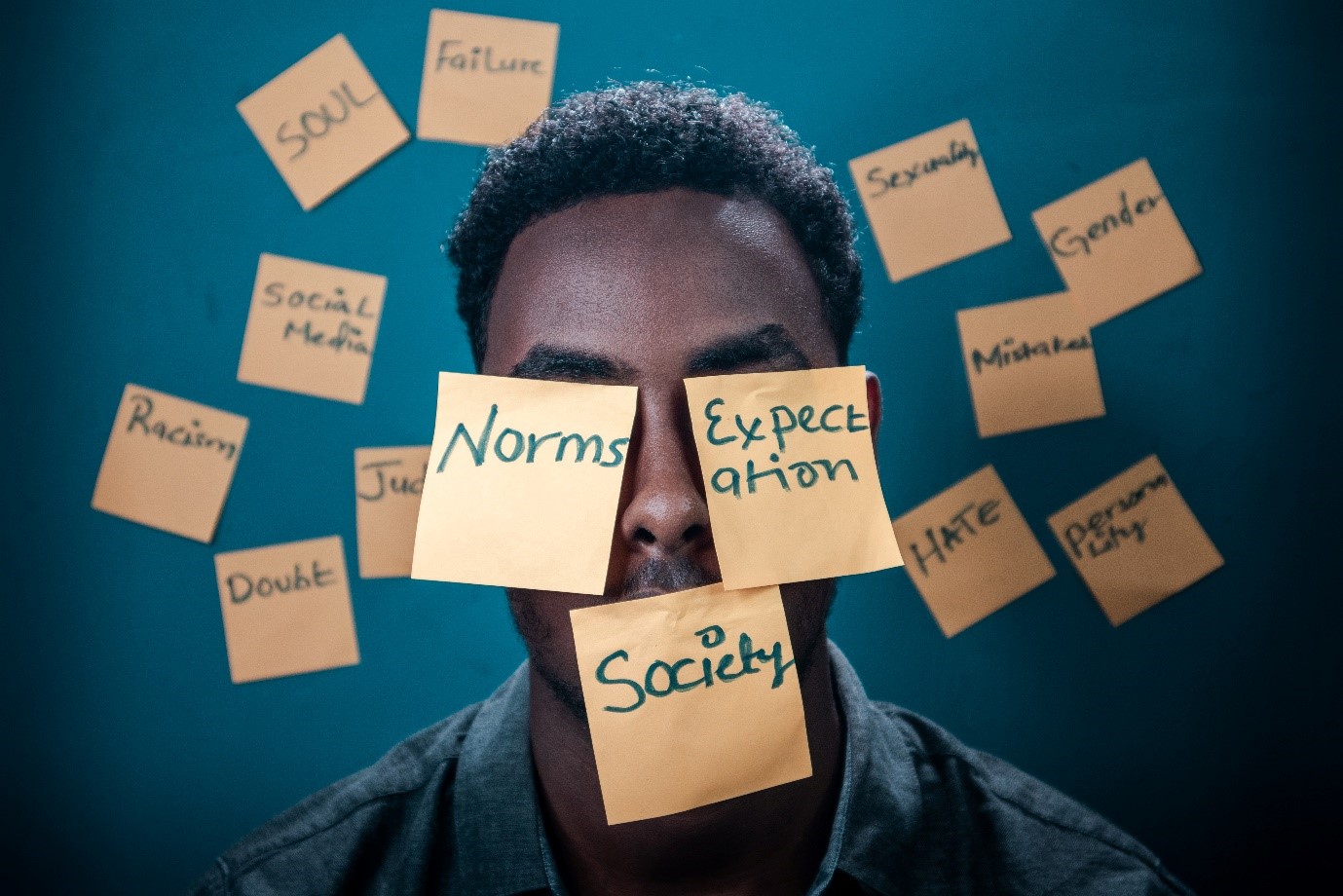

Black and white interests have always been carried by different political parties. On the one hand, black people used the African National Congress, the Inkatha Freedom Party, the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, etc., to express themselves and their interests. On the other hand, white people used the National Party, the Vryheidsfront Freedom Front, the Democratic Party, etc. Black parties have always received the majority of votes. Even in the recent elections, the black parties are in the lead, although they are divided, and the number of political parties has multiplied—from 14 to over 50 parties. However, there is a notable and worrisome shift in these elections. There is an insidious resurgence of white consciousness that influences the outcomes of the elections. White consciousness, underpinned by racism and white supremacy, lost political power to black people in 1994. Yet, through organizations such as the Democratic Alliance and Freedom Front Plus, white consciousness is pushing hard to resurge and reclaim its ground in the state. Although these organizations do have their differences, they are secondary. Their primary interest is to maintain white privilege. It was worse in these recent elections since, as a result of its desperation for this resurgence, the Democratic Alliance has been accused of rigging during the counting of votes, especially in the Western Cape. This is not their only strategy, as for years, the Democratic Alliance has exploited many black people to the extent of using some as the face of their campaign to gain votes from the black population.

The rise of this white consciousness has to be opposed. There is a need for counteraction to combat white supremacy and white dominance to defend the little that the post-1994 dispensation has gained and for the continuation of the struggle for the total liberation of black people. The renaissance of white power will ultimately lead to the reversal of all the achievements of the black government. To counter this resurgence of white consciousness, I suggest there is a need to go back to Steve Biko and his black consciousness philosophy. While many anti-apartheid organizations hastened to fight for “one man, one vote,” Biko and his peers advocated for more than that. Psychological liberation for black people was preeminent for Biko. Having experienced racist apartheid in South Africa, Biko suggested that the main and fundamental issue of concern was whiteness, which perpetuated white domination and white privilege. For him, to fight this whiteness and white consciousness, there was a need for black consciousness and solidarity among the black community in South Africa. Biko gave blackness an identity beyond the color of the skin. He posited that black people are those who are subjugated, oppressed, dehumanized, marginalized, and excluded by the system of white power and privilege. For him, black people are the victims of whiteness. They are those in the structural position of disadvantage and inferiority, while whiteness reserved the structural position of advantage and superiority for white people.

The question of identity was sacrosanct for Biko. Hastening to cast a vote without a black conscious attitude and identity for black people—an identity that is a negation of whiteness—was never a solution. A slave with Stockholm syndrome sees their master as their savior—that is, a black person without black consciousness. Unfortunately, the racist and brutal apartheid regime could not let Biko and black consciousness find expression. Biko was murdered; black consciousness was suppressed.

With the recent elections and the current political dynamics, it is now evident that for political parties to get an absolute majority is a thing of the past. The dropping of the ANC to less than 50% attests to this. No party today or in the foreseeable future can form a government of its own without having to work with another party. South Africa has just entered the era of coalition government. Seeing different parties make compromises to govern together is the new order of the day. This form of government, among its many critics, has the potential to reassert white political power through the control of the state. This is going to be a big win for white people, as the state would be used to protect and perpetuate white privilege and white dominance, as it had been the case before. This will be possible when black parties desperately join hands with white organizations such as the DA.

The current juncture requires that black people go back to Biko and his ideas in the archives. There is a need for black people to see each other beyond party lines. There is a need for a black consciousness attitude and identity among black people to cling to each other with a tenacity that will shock the perpetrators of evil—white supremacy. The question of belonging to either the Economic Freedom Fighters, the uMkhonto Wesizwe Party, or the African National Congress has to be secondary, as what draws the distinction between these organizations is not a primary contradiction. People belonging to black organizations that supposedly represent the aspirations of black people have to have a point of convergence, and that is black consciousness, as coined by Biko. Biko himself worked tirelessly to push for the formation of the front that would bring together black organizations. Despite being a founding member of the Black Consciousness Movement, Biko had met with leaders of the PAC, including its founding president, Robert Sobukwe, and he had arranged to meet the president of the ANC, Oliver Tambo, when he untimely died. Biko’s aspirations far surpassed party politics, and he was keen to bring black people together in solidarity and inculcate among them black consciousness against white consciousness, which carries in itself white superiority and dominance.