Francis B. Nyamnjoh is a world respected cultural anthropologist based at the University of Cape Town. Originally a native of Cameroon, he has been working in the Southern African region for a few decades beginning in Botswana. He also had a stint working at CODESRIA, Dakar, Senegal as Head of Publications at the organisation.

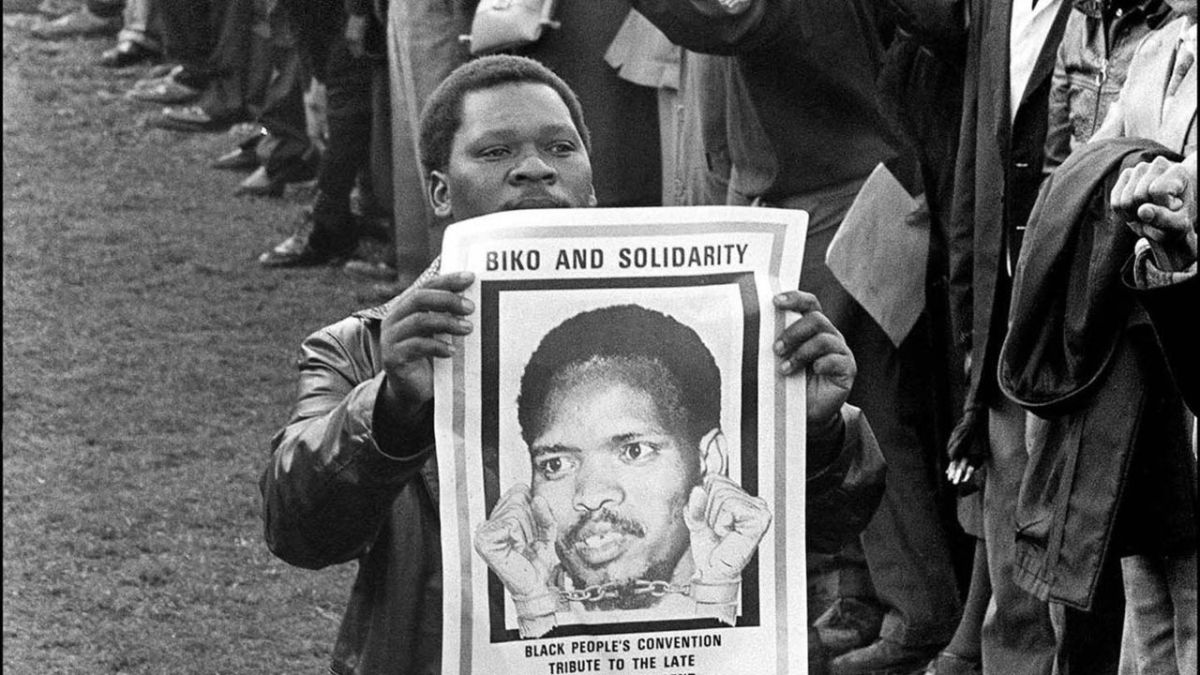

A highly prolific scholar, his latest book, Incompleteness, Mobility and Conviviality (2024) was developed from the Ad. E. Jensen Memorial Lectures that he delivered at the Frobenius-Institut, Germany. In this new offering, which has a preface supplied in both English and French by German- based professor of anthropology, Mamadou Diawara, Nyamnjoh revisits most of the academic terms he had previously explored in his earlier publications such as #RhodesMustFall: Nibbling at Resilient Colonialism in South Africa (2016) and Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd: How Amos Tutuola can Change our Minds (2017). The earlier book attempts to unpack the historical as well as ongoing legacies of the preeminent coloniser of Southern Africa, Cecil John Rhodes, in the wake of #RhodesMustFall movement that spiralled out of the University of Cape Town in 2015. In addition, Nyamnjoh further interrogates the insider/outsider or alien/citizen dichotomy that has become part of central features of the contemporary world. It seems in our common quest for belonging, there is also the compulsion to ostracise and dehumanise others. Much of Nyamnjoh’s earlier research outputs interrogate this unfortunate dynamic. Similar traits can be discerned in the development of global capitalism. For instance, in order for Rhodes to amass his ill-gotten wealth, there was a concomitant trail of dispossession, devastation and death left in his wake.

Nyamnjoh alludes to the turmoil and violence caused by the colonial encounter. As Africans, we are condemned to search for an illusion of ‘completeness’ after such a devastating historical experience. Ordinarily, the quest for completeness would be condemned to futility because we are grappling with the debris of a largely annihilated world. However, in an age of resurgent Afropessimism, Nyamnjoh is able to furnish lavish amounts of humanism to serve as a salve for our severely wounded psyches.

Principally, he accomplishes this in at least two ways. First of all, he questions the project of anthropology in its largely unreconstructed colonialist guise. In other words, Nyamnjoh advocates a decolonisation of anthropology together with its biases and assumptions. Secondly, he argues for greater ‘intimacy ‘between disciplines in the social sciences and humanities such as between literature and anthropology.

In pursuing this line of argument, Nyamnjoh uses the work of famous (some would argue cult) Nigerian writer, Amos Tutuola as a foil. Born in south-west Nigeria in 1920, Tutuola only received six years of formal schooling but was able to author eleven novels most of which were published by the reputable British publisher Faber & Faber beginning with The Palmwine Drinkard in 1952. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, a title made famous by New York new wave rock combo, Talking Heads, with their 1981 album of the same name, followed in 1954.

However, before the publication of Tutuola’s first novel, Faber & Faber had sent the manuscript to anthropologists rather than literary scholars for critical evaluation. Even Chinua Achebe had been initially subjected to the same treatment. This trend initiated the anthropologisation of literary texts produced by Africans which was something that was later decried by Anglo-Ghanaian philosopher, Kwame Anthony Appiah, by employing a memorable phrase, “typologies of nativism”. For Nyamnjoh, it would appear that the anthropologisation of literary texts is an act of colonialist violence. Nyamnjoh explains that this violence was not only perpetrated by colonial agents against Tutuola but also by uptight Nigerian intellectuals who were scandalised by Tutuola’s anti-colonialist subversion of the English language. Those offended intellectuals had hoped for a racial ‘coconut’. In other words, a Fanonian caricature or rather a decent (mis)appropriation of his metaphor, ‘black skin, white masks’ as a quasi-civilised representation of the African exposed before a still colonised, and barely reconstructed world. Nyamnjoh, on the other hand, rejects this colonial misrepresentation in its entirety. Rather than follow the preferred academic route of anthropologising Tutuola, Nyamnjoh has been involved in affirming his literary qualities. In this way, he is both re-reading and re-writing the classic colonial script.

However, a major merit of Nyamnjoh’s operation is the resistance to succumb to depths of despair and violence in freeing the colonised consciousness from the vice-grip in which it had been inserted.

Fortunately, Nyamnjoh is also able to point out a way out of this quandary. Here, the concept of conviviality is introduced. A way of better understanding the term is to employ the Southern African concept of ubuntu. Nyamnjoh attempts to view conviviality as a widespread indigenous technology of sociality. In some of his other writings, he has also employed the popular West African delicacy, palava sauce as a way to understand what conviviality in action means. During social occasions when members of a community gather to enjoy a dish of palava sauce, social or communal tensions are usually addressed and resolved. More than just its tasty nature, palava sauce is employed as an antidote to acrimony, bad faith and sociopathy.

However, the concept of palaver dates much further back during colonial times when Dutch, French, Spanish and Portuguese colonialists trawled Africa looking for different kinds of conquests and opportunities for plunder. Indeed, those were highly fraught times and Africans had to navigate often treacherous terrains to conduct trade and commerce with a wily enemy. The notion of palaver was introduced to facilitate ‘amicable’ relations under the ever-present shadow of dispossession, enslavement, or worse, even death. Indeed, Africans fine-tuned the concept of palaver as a necessary strategy of survival.

Nyamnjoh suggests that the devastating consequences of the colonial encounter do not necessary entail the end of African ingenuity and creativity. Rather, by adopting innate endowments of conviviality, it is possible to re-invent ourselves in multiple ways. It is also quite possible to re-write our futures drawing on the same ontological resources of resilience and need one add, resistance.

Essentially, the concepts-incompleteness, mobility and conviviality- Nyamnjoh has chosen to probe almost exclusively in this book are part of what make us fundamentally human.

Even more, Nyamnjoh in his latest release, nicely ties up most of the recurrent theoretical concerns and concepts in his thinking which should in turn also re-ignite interest in his earlier work.

*Sanya Osha is a Cape Town based scholar and author.