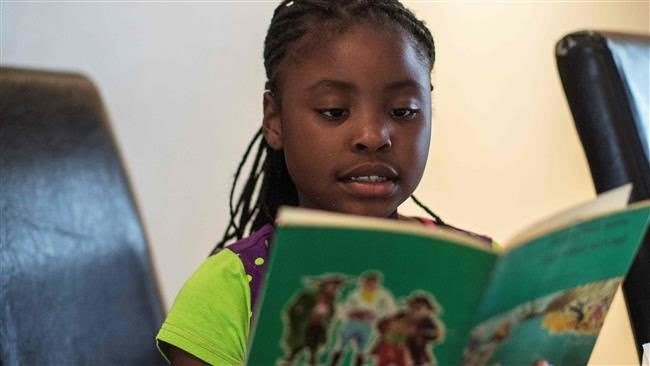

Michelle Nkamankeng’s feats, as a budding South African author (currently of fiction), invites attention for most fans, interested in children’s literature.

This 12 year old starlet, was born on 23 December 2008, in Gauteng. She is a grade 7 pupil at Rand Tutorial College, in Observatory, Gauteng. She is the third child to her proud parents, Paul Nkamankeng (her father) and Lauritine ‘Lolo’ Nkamankeng (her mother and diligent manager). According to her mum, Michelle Nkamankeng initially showed interest in reading, at the tender age of four, while a student at Sacred Heart College (SHC) in Observatory. Then from five years on, she progressed from an avid reader to an avid writer.

Chronologically Michelle Nkamankeng’s quest of penning children’s books commenced while six years old, however, her initial book was only published once she was seven years old. Dual factors of parental support and a conducive learning milieu, may mostly illuminate this adolescent author’s potential knack for writing at an early age.

Let’s crisply reflect upon Michelle Nkamankeng’s first three books. Titles of her available books include Waiting for the Waves (2016), The Little Girl Who Believes in Herself (2018) and The Little Mouse (2019). This nascent author, astonishingly remarked in manifold interviews, that she is presently busy with what may become her eighth book.

Her fourth book, entitled The Golden Ring, is still unpublished. Given the overwhelming presence of ‘white’ characters in children’s books, it can’t be downplayed how invigorating it is that the aforesaid initial two book, mirror characters consistent with the author’s race, as a ‘black’ child. The first book Waiting for the Waves (2016), completed on the 31st of March 2015 was, however, only published during September 2016.

This tellingly reflects that the author was only six years old, doing Grade 1, when she began her literary venture. This first book’s protagonist is a little ‘black’ girl named ‘Titi’ (no surname given), who is supported by a cast comprising her ‘black’ family members, led by her caring (read responsible) ‘Uncle Joe’. This story is “about a little girl who loved the ocean and the big waves” (Nkamankeng, 2016). This book realizes its aim, of telling a “story that highlights contradictions of emotions” (Nkamankeng, 2016), to inspire kids to confront their fears.

Although the second book The Little Girl Who Believes in Herself (2018) was completed shortly after the initial book in 2016, it was however only published in May 2018. This was observably while its author was in Grade Two, aged 7 years old. The leading protagonist in this book is a seven year old ‘black’ girl (note the link with the author’s real age and race) named ‘Nida Minah’. Oddly the latter character’s surname is absent at the beginning of this story, negligibly appearing as late as in page 40. This is one of the red flags, indicating how much improvement this nascent author still needs en route to become an astute writer. In sum this book is “about a little girl who after conquering her fear starts gaining confidence and begins dreaming big about what she wants to be in life” (Nkamankeng, 2018). Put differently, Nida Minah harboured a dream of becoming a medical doctor and after dedicating herself to lessons relevant to medicine, she prospered to realize her dream. The message of this book, to inspire kids to ‘not give up on their dreams’ is achieved. Perseverance may be testing however endurance has its rewards.

The third book The Little Mouse (2019) is about an “exciting cat and mouse game” (Nkamankeng, 2019). This book was poles apart in twofold ways, from the preceding two books. Firstly the protagonists in this book, namely ‘the little Mouse’ (later named Jerry by the young ‘white’ boy Tom) and Luika the Cat, shifted from a focus on somewhat real human relations in favour of animated depictions of animal relations. The chosen names and cast of characters scream out loud that the juvenile Michelle Nkamankeng’s foremost inspired source for this book was the animated cartoon series ‘Tom and Jerry’. This aforesaid first distinction from the preceding two books, may also help to decipher the second reason why even the racial profile of the fictitious human characters in this book shifted from ‘blacks’ and replaced it with ‘whites’. With that said, the key message of this book is still achieved, of warning people from falling victim, to relationships whence their trust, is taken for granted and abused. Overall, albeit Michelle Nkamankeng’s pros and cons, it is only fair that at this stage, readers will have to await the availability of her imminent books, in order to articulate prospective sought-after reviews of her mounting oeuvre. Suffice to say, however, that given the clarion call to ‘decolonise South Africa’s Curriculum’, her first two books aptly mirror her reality as a young ‘black’ girl, which is relevant to us as her ‘black’ readers. In contrast her third book reminds readers of overlooked influence, of animations upon promising minds of all racial hue in our locale.