On the set of a horse ranch in modern-day United States, Jordan Peele returns to traditional storytelling and clarity in their latest film, Nope while maintaining a unique ethereal output and repackaging classical horror tropes with social commentary. Spoilers ahead.

NOPE’S NECROPOLITICS

The extended theme running through Nope is predation. Peele presents the concept of a predator as a seemingly unstoppable force untamable by nature, creating clear rules for how predators operate. Don’t challenge them by looking them in the eye. Don’t hold them in captivity. Make deals with them to survive.

Typical of Peele’s films, this explanation of a predator could be extended into social issues like colonialism and genocide where imperial forces or ethnic powers serve as “predators” — forces with access to violence and the motivation to enforce necropolitics (necropolitics is a word which means the power to choose who lives and who dies).

If this is terrifying, that is Peele’s point, that being subject to the whims of a more powerful entity, to be forced to hide away (a recurring defense employed by the characters in the film) or to simply keep one’s head down (a metaphor for voluntary subjugation) is a horror.

In Nope, characters are terrorised by an extraterrestrial ‘animal’ which roams the sky, descending routinely to absorb and eat human beings. Why? Well, the characters in the film are not entirely sure, but the film suggests that the only explanation for its actions is that the alien lifeform is establishing control over territory.

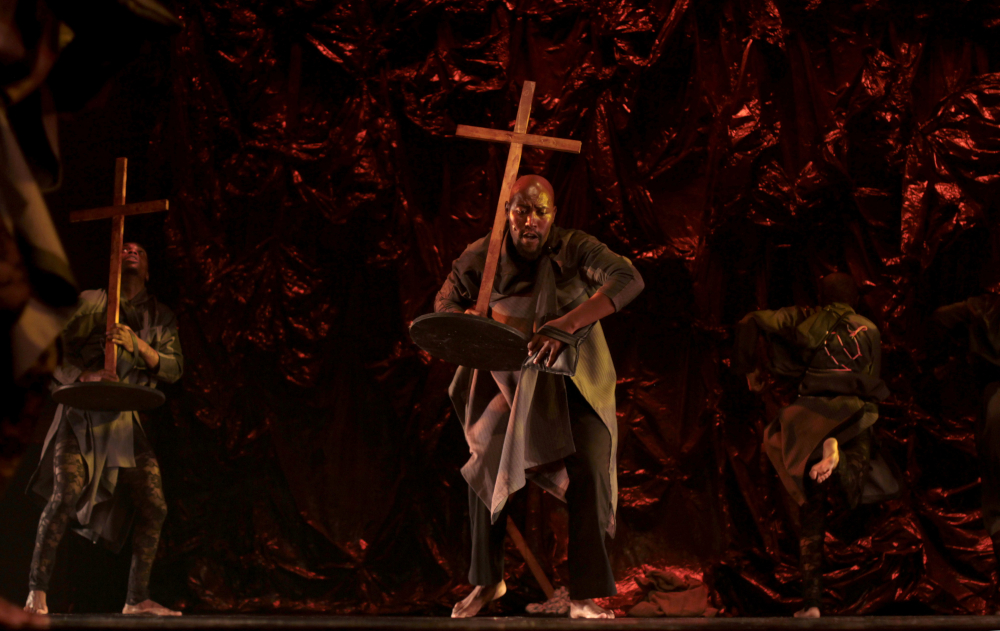

The predator extraterrestrial in Nope chasing OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya).

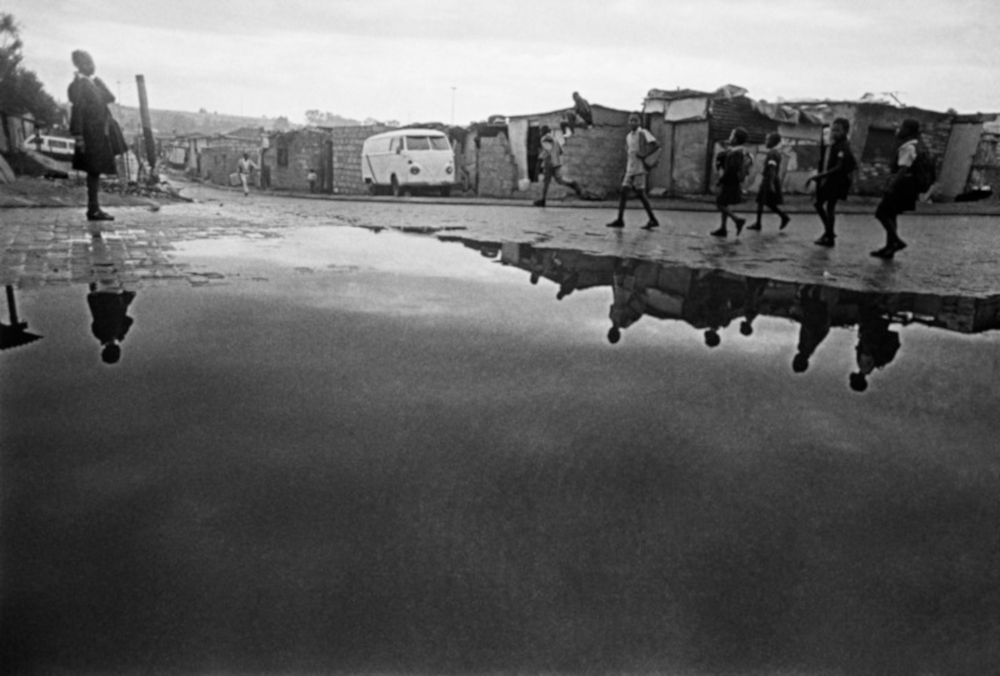

This is similar to the general philosophy that Achille Mbembe reasons in Necropolitics (Theory in Forms), where the foundations of modern society are preceded by acts of oppressive violence and horror. In fact, according to this philosophy, modern society was founded by these atrocities.

A significant similarity between the predator in Nope and Mbembe’s Necropolitics is the concept of a nocturnal body, which is the hidden form of a structure that serves to use violence to form itself, and is distinct from the seemingly non-violent solar body. In Nope, the alien hides in the clouds for most of the day, going to hunt during the twilight or when it feels intimidated. This is the nocturnal body of the film’s predator which the characters in the film set out to document.

This is an interesting storyline in the film, because all which the characters want to do is take footage of the predator, and not necessarily defeat or kill them. This is similar to the role of the oppressed in writing about concepts like necropolitics, attempting to reveal modern society’s violent foundations.

As the film reveals, it is not easy to grasp the predator. They fly high in the sky, move fast and are very deadly. The best the characters can do for most of the film is run and hide. But they are motivated to photograph the predator, which is a way of grasping the horror by capturing it. The film’s characters face multiple obstacles attempting to achieve this. Their electric-powered cameras, even higher advanced models, turn off when the predator is near. The nocturnal body resists being seen by the tools of modern society.

Ultimately, they use manually powered film equipment, but all of this footage is lost when the predator attacks again. Finally, through great effort, they capture a single photograph of the predator. That’s the best we can achieve, to only glimpse the nocturnal body.

After all, how do we gaze into history and find all its acts of violence that have been covered up, erased, and ignored? How do we prove that violence has occurred in spaces where no one looks? Nope does not give us a clear answer, but dares us to keep putting in the effort to try, and maybe capture the nocturnal body, the horror.

CONCEPTS NEED CHARACTERS

Conceptual film characters present a serious challenge. The more conceptual or thematic the character, the less ‘real’ the character becomes. This is generally a major flaw in Peele’s earlier filmography (Get Out, Us) where characters are placeholders for developing the theme of the storyline, but are not presented as complex human personalities. The characters in these earlier works are not memorable and the films seem to exist only to communicate its themes. But film is a medium that can uniquely showcase complex human connections, character flaws, oddities and conflicts. While themes are important, the point of making a film is to showcase plot and theme through rich, memorable characters.

Much of this flaw is rectified in Nope, where human bonds are explored as ends themselves, and not necessarily just for the purposes of developing the plot. For instance, the sister-brother dynamic between OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald Haywood (Keke Palmer) is seriously pursued, mirroring real-life familial bonds. There are moments in Nope dedicated to developing characters (while simultaneously reestablishing the film’s theme), in ways that intersect with the storyline but are not subservient to it. For instance, Ricky 'Jupe' Park (Steven Yeun), is given a significantly established background narrative which develops as the film progresses.

OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya), Emerald Haywood (Keke Palmer), and Angel Torres (Brendon Perea).

Peele cleverly reinforces the theme of predation and violence, by showing Ricky’s traumatic childhood event, where an ape murders the characters of a sitcom on set. This gives Ricky a rich complex character history, revealing that their present-day nonchalance and charm is a performance. Further, it gives evidence to the theme that predators commit acts of violence. So, it is possible to develop a film’s themes without compromising its characters.

Compare the ‘sidekick’ character, Rod Williams (Lil Rel Howery) in Get Out to the salesperson-turns-friend, Angel Torres (Brendon Perea) in Nope. Rod Williams serves as comic relief and unexpected ex machina, whose participation in the film is largely unnecessary, except to miraculously save the story’s hero in the final arc. However, Angel Torres is an integral character in Nope, who participates throughout the film and whose character creates bonds with the main characters.

Ultimately, concepts need characters to be conveyed adequately through film. It is through these intense connections that the film medium explores what it means to be human.

NOPE. NOPE. NOPE

A particularly witty moment in the film occurs when OJ looks at the predator in the sky and repeats, “Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope”. It’s a moment of relatability for the audience that reacts similarly to the ‘monster in the sky’. The film actually gets away with using this line twice.

There are many clever quips employed in the film, such as teasing at what the horror in the film will be by having Ricky’s children dress up as aliens and trick audiences into thinking they are the film’s monsters—or through the jump scare of a praying mantis hopping onto the Haywood’s surveillance camera. Peele shows deliberate effort to subvert classical horror tropes, with scenes where a swinging door shows and reveals a person being murdered, a house is covered in blood, or a co-worker sneaks up from the darkness.

Then, as soon as the true horror of the film is revealed, Peele directs a very serious film with a clear story arc. The characters’ objective is to film the predator. The conflict is they have to do this without being killed. This is a traditional story structure that audiences can appreciate, in contrast to the use of surprise twists in Get Out and Us. By using gimmicks and then immediately dropping them for the rest of the film, Peele shows that they can direct a serious film-like-film, while still maintaining their unique quirky signature.

Ricky 'Jupe' Park (Steven Yeun) reveals the horse, Lucky, as an offering in the direction of the predator.

After all, much of the film is impressive, when compared to previous works. But there are still some structural problems with the film that should make us say, “Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope”

For starters, Nope is not really filmed as a horror film. Its style, colours, quips and storyline are more akin to a sci-fi-esque adventure film (but for mature audiences, instead of young children), but simply using horror tropes. In a typical adventure film, characters set out on a mission or participate in a non-mandatory objective. They don’t really have to do something, but they want to, or feel compelled to. In Nope, the characters don’t have to stay at the ranch. The predator does not hunt them if they leave. They could have left, but they chose to stay at the ranch to take a picture of the predator because they wanted to. Emerald has shallow motivations but OJ seems driven by a sense of duty to stay. He has work to do, he claims.

But, horror is more akin to conditions where characters are forced into terrors, with no escape. Characters usually have little agency and even if they tried to run, the horror would follow them. Further, Nope was not an unsettling film. It was light and thematic. We were rooting for the characters to succeed. We weren’t gasping at their possible demise. That’s exactly what an adventure film makes audiences feel. It’s okay that Nope is attempting to recreate adventure themes for more mature audiences, but it is not a horror film.

Certainly, there are avant-garde or historical horror films that are much different to typical Hollywood horror films, but that is not what Nope is trying to do. It is actively trying to not be a horror film, but to rather tell an interesting and adventurous story. In fact, all the horror tropes could be taken out of the film and the general message of the film would remain intact. The presence of violence and gore does not make a film a “horror”.

There are many dynamics that Peele employs in their filmography which are seemingly done for the sake of employing them. It’s not clear what value Nope gains from being set on a horse ranch, apart from creating room for “hidden meanings you might have missed”.

The Haywoods are horse ranchers but we rarely see them really doing horse-ranch related activities. Peele does not really attempt to show us life on a horse ranch. Instead, it’s just used as a setting for the film. It sets up a ‘cool’ horse-riding scene in the film’s climax where OJ leads the predator into the view of the filming equipment. It is ironic because in the film, near the horse ranch, is a Western-themed theme park, but the horse ranch itself feels like a set. The environment where the film is set seems redundant.

Peele tries to reference the mythology of the first motion picture shot being a black person horseback, which is then mirrored by OJ being captured horseback on film, just like the supposed first shot in film history. We get it. Peele is making a direct reference within an indirect reference. A frame within a frame. A movie with horse riding that is conscious of the fact that movies were launched by horse riding. It’s an interesting concept to explore, but it appears to be employed for the sake of employment. The concept is just equipment for the film, but not something the film earnestly explores.

Peele’s references to history lack real investigation or depth. Their symbolism is ultimately surface-level with audiences reading the substance into the ice-berg tip of how the film presents its symbols. One of the problems with making overly-light-hearted and overly-abstract films is that the use of real-world deep themes are filtered through an eccentric flat lens.

Nope is a thoughtful film when we write about it, opine on it, but Peele does not present a thoughtful film. Nope feels like the first draft of a brilliant film, which can only be developed by taking itself more seriously. If it wants to cover dark serious themes, the film will have to become darker and serious itself.

Fundamentally, Nope, is itself a solar body, a film that hints at, but does not really show itself. There is a version of this film which is truly a horror, which is dark, which is serious and really would make audiences say “Nope. Nope. Nope. Nope.”