Imagine you are a mink – beautiful and precious beyond compare. Then suddenly one autumn day, hunters invade your homeland.

Unsuspecting, you receive them with open arms, in accordance with minkdom’s time honoured customs. You order a feast in their honour: calabashes of frothing minkinut beer, goat meat and beef with ting and morogo. In the evening you entertain them with song and dance in which the whole community participates, including your minkitots and their zonkitots. At the end of the day’s festivities, you offer them a place to sleep. They return the next morning and ask if they might stay longer. You apportion them a place to stay, grow their own gardens and keep stock. You give them a few start-up chickens, goats and cattle. At first, nothing in their conduct alerts you to the fact that their intentions are less than honourable. They seem kind and pet your younglings, who are impressionable, innocent, and trusting. To your women they give shiny trinkets for presents.

One or two minks with a reputation for bickering and objecting to everything warn against the new arrivals. A soothsayer with a waning reputation also warns, as she is being dragged to be hurled down the donga of death for crimes of sorcery: “Niyangibulala? You’ll never rule over this land. I see white vultures readying themselves to pounce on you.”

“Indaba ithungelwa ebandla,” the King Mink I pronounces, stroking his greying beard that he wishes was as long as the head hunter‘s. And having assembled the mink tribe and allowed them to deliberate at great length, he pronounces: “We shall treat the strangers in accordance with our time honoured customs. Our forebears coined a saying by which we‘ve always lived: Ukwanda kwaliwa ngumthakathi.6No mink’s life has meaning except in relation to others. It is not our tradition to deny hospitality even to complete strangers.”

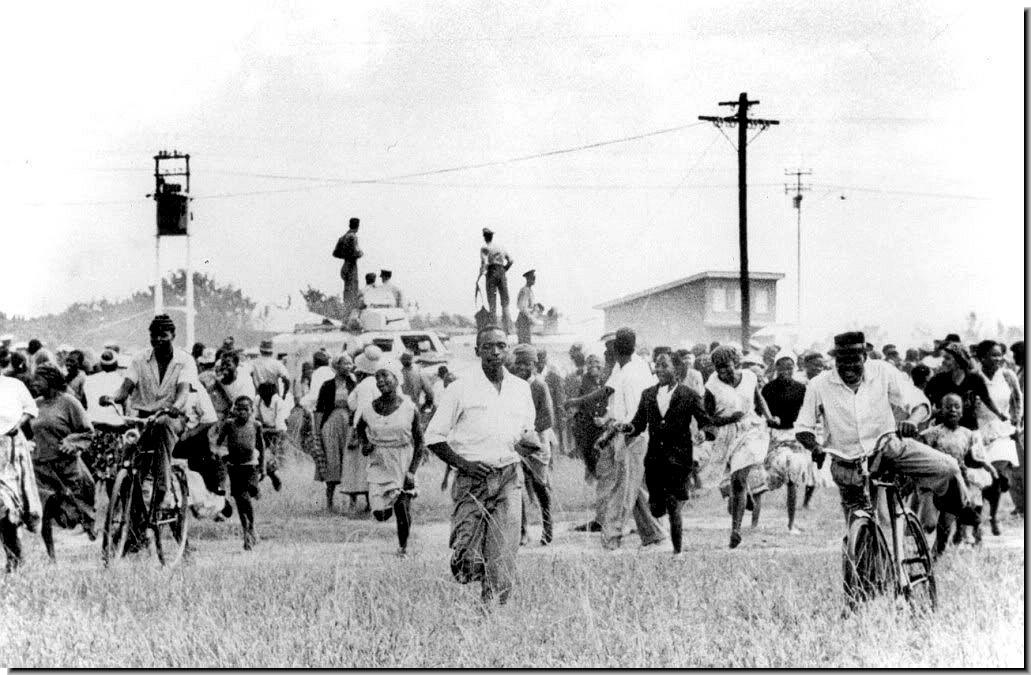

Then, with the suddenness and ferocity of an African thunderstorm, the hunters attack and beat you. You are dazed and struggling for composure.

“Hawu! Is there anything perhaps we should have given you that we didn’t?” you ask.

“Don’t you have enough land, enough chickens, goats and cattle? Or is it you want us to give you our daughters in marriage as well? Tell us, we will provide any of these things.”

“Give us your fur!” they say.

Somehow, it doesn’t make sense. The very thing that makes you who and what you are becomes the source of your excruciating pain, as they assail you time after time because of your beautiful and precious fur.

Confused and mistrustful, you go into hiding, camouflaging your fur. They hunt you down and flush you out from your cave hide-out along the slopes of the Amatola Mountains and from your forest fortress at Hoho. They strip you of nature’s protection and your disguise, leaving you feeling exposed and vulnerable -- while imbongi yesizwe jikelele composes mournful songs that express the community’s incomprehension, deprivation, sadness, loss:

Senzeni na? What have we done?

Isono sam bubumnyama... My minkinity is my awful sin...

Hay’ usizi lomntomnyama… What burden minks bear

Emhlabeni! In this world!_

Zonk’ izizwe zisibeka Every other species

Phansi konyawo. Tramples them underfoot.

The hunters return, season after season, nine in all, until you begin to understand that you will never get away from being who and what you are. As long as you have fur, you will be hunted. They steal your skin, your heritage, the very essence of your minkinity. You are still dazed and struggling for composure. They leave you to die but you survive. Become stronger. Your fur grows. More beautiful, more lush than spring grass.

The minks’ growing strength and beauty coincide with the return of the hunters amidst a gathering storm in the land that becomes fiercer with each passing day.

The hunters shudder and take fright at nature’s reminder of the grimness of their ways. They ask one another -- and their zonkitots, too, begin to ply them with questions they don’t know how to answer: “What if some day, in the thick of the night, with the storm wreaking havoc upon the land, the hunter should become the hunted?”

The zonkitots pull at the legs of their fathers: “Daddy, daddy, daddy, I’m afraid of the mink.”

“Quiet! Can’t you see your father is thinking?” The mothers hush their babies, with sidelong looks at the fathers, who stare straight ahead with unseeing eyes.

The zonkitots start a wail that haunts the hunters every time they leave home for the hunt and every time they return home from the hunt.

“Quiet! Can’t you see your father is tired? I’ll call the mink and he’ll eat you.” The

mothers, wearing long faces, threaten their restless offspring but to no avail. A tiny tot bawls in terror and is hushed by an older sibling.

The older zonkitots go out to play catch-me-if-you-can and compose a rhyme to go with the game:

My children! Bantwana bam!

Yes, mother. Me, Me.

Come over here. Izani apha.

We’re scared. Siyoyika.

Of what? Noyika ntoni?

Of minks. Ingwe.

Where are they? Iphi?

Over there. Nansiya.

Run away... Balekani ke?

The zonkitots’ chase re-enacts the hunt from stories they’ve heard their fathers tell. The games of the older zonkitots bring little joy, however, to the hunters haunted by wailing babies every time they leave home for the hunt or return home from the hunt. The thrill of the hunt starts to diminish. Spine chilling fear takes hold of their nerves of steel. They call an emergency town meeting.

There is an unprecedented turn out at the meeting. There is standing room only at the town hall, with the zonkitots hanging precariously from the windowsills.

“People of the hunt,” the head hunter begins, “we have summoned you to this town meeting to discuss a matter of grave concern that affects the future of every inhabitant of Huntsville. Some of you have been asking if it is at all likely that someday the hunter may become the hunted. In years past, the answer to that question would have been a simple one: You can’t hunt with your bare hands. To be a successful hunter, revered throughout the land, you need weapons that are more than toy weapons. Today, however, we can no longer answer with the same degree of certitude. Even weapons of mass destruction are freely available in the open market and training provided for whosoever wishes to master their use. While until now we’ve had little cause for concern over the minks’ prolific breeding habits that assured us of limitless game, today their growing number that far outstrips ours poses a grave threat and the game reserves can no longer contain their population explosion.”

The questions from the women and zonkitots gush out like flood waters, and the head hunter keeps shaking his head at each question.

“Where do they get money?”

“Who provides them training?”

“Can’t we hunt down and destroy all those who provide them support?”

“Can’t we increase the size of the game reserves?”

“Wouldn’t it be simpler to cull them?”

“Is it possible to drive them all up north, whence it is said they came?”

“What does the future hold in store for us?”

The frail and the elderly, women and workers, the usually silent majority, all speak up. The debate rages deep into the night.

“We have debated the matter long enough,” the head hunter finally declares. “We all know the nature of the problem. What’s important is to determine what to do about it. We have heard your concerns. The meeting is adjourned. Your volksraad will remain to deliberate over the matter and prescribe a lasting solution to the problem. You will know by this evening what we decide upon.”

The volksraad decides to place the matter to a referendum. The Huntsville community resolves, by a sizable majority, that the time has come to devise new ways to protect their amassed furs.

Next day, they send a delegation to Minksville to make a pact with the minks that will promote constructive engagement and peaceful coexistence. Together they draw up new protocols to determine how to govern the land in order to ensure lasting peace and sustainable development that all may multiply and prosper.

The minks cooperate but most show themselves to be less interested in material accumulation and more enamoured of the prospects the New Deal offers for the protection of the sanctity of life and the restoration of their dignity and minkinity. A few greedy ones among them, however, have started to salivate like Pavlov’s dogs.

The two sides engage in protracted negotiations to draw up further protocols that assert and protect the rights of all to live in peace and harmony. They also agree to hold elections on a common voters’ roll to determine who will govern the new nation-in-the-making in the State of Gondwana.

On the appointed day, the minks shine their fur, now grown to a lush softness, and swarm to vote -- alongside the grinning hunters, their muskets now in storage. They elect a new leader of all the inhabitants of Gondwana -- a tall, frail looking, silver furred elder with impeccable struggle credentials; a mink of infinite fairness, lasting commitment to reconciliation, immense integrity, a forgiving heart and abiding faith in minkinity.

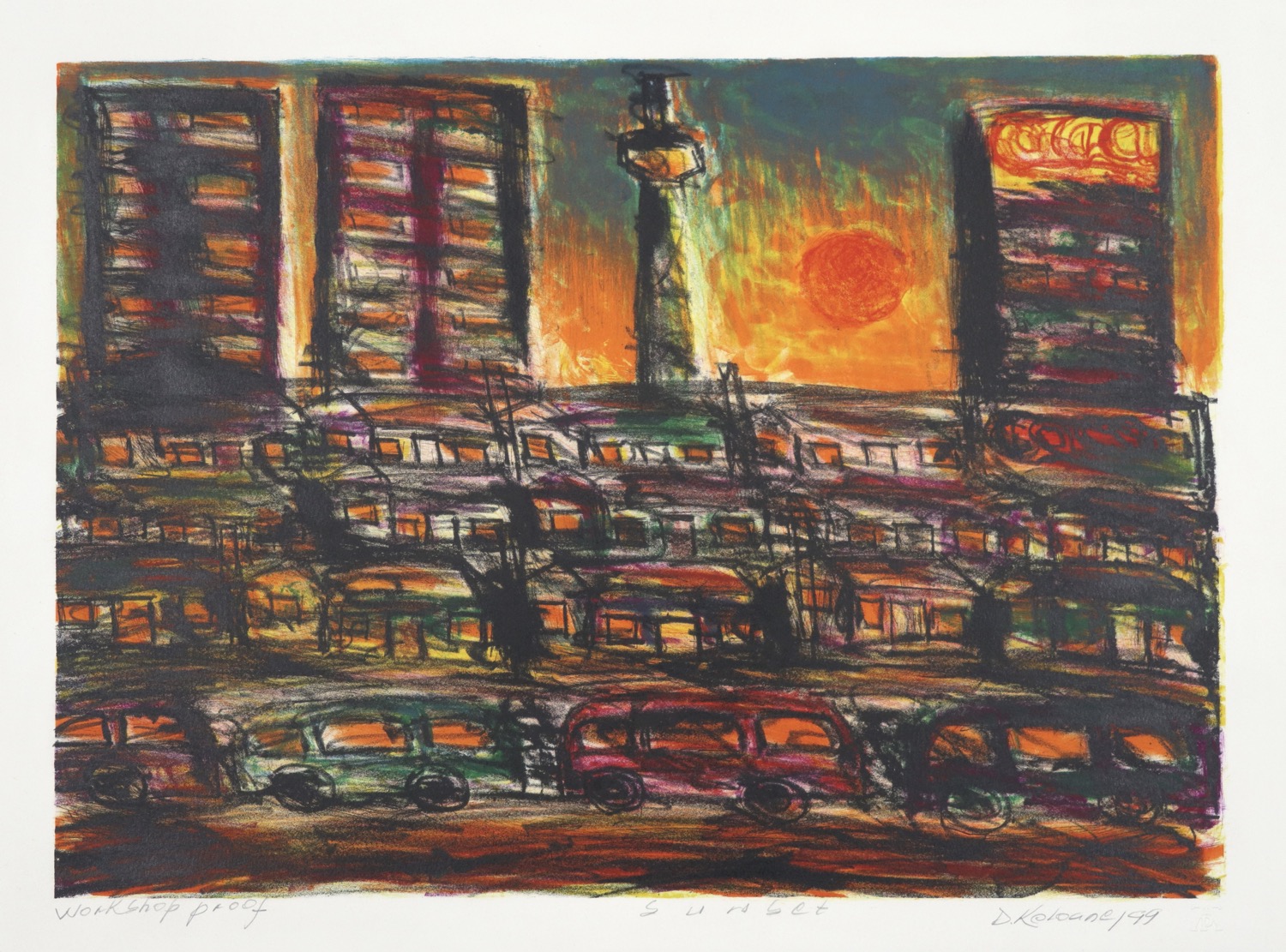

To cement their triumph, the inhabitants of Gondwana throw up the mother of allparties. In accordance with time honoured custom, they prepare a feast: calabashes of frothing minkinut beer, goat meat and beef with ting and morogo, and koeksisters for dessert. The festivities continue into the night with song and dance in which the whole community participates gleefully. All join in singing the new song the imbongi yesizwe jikele composes-- a song that expresses the nation’s new understanding, salvation, gladness, recovery:

Gondwana our motherland

None among others is fairer.

From coast to hinterland

Prosperity comes ever nearer.

Forward! Phambili! Kopele! Voor!

The silver furred one, his heir apparent beside him, a short mink with eyebrows starting to turn silver, stands stiffly at attention, staring straight into the distant horizon, as the citizens of the new State of Gondwana sing lustily to heaven:

Arise, oh, compatriots

Obey Gondwana’s call.

Gunshots are heard -- and some minks take fright -- but the program director explains that it is only a twenty-one gun salute.