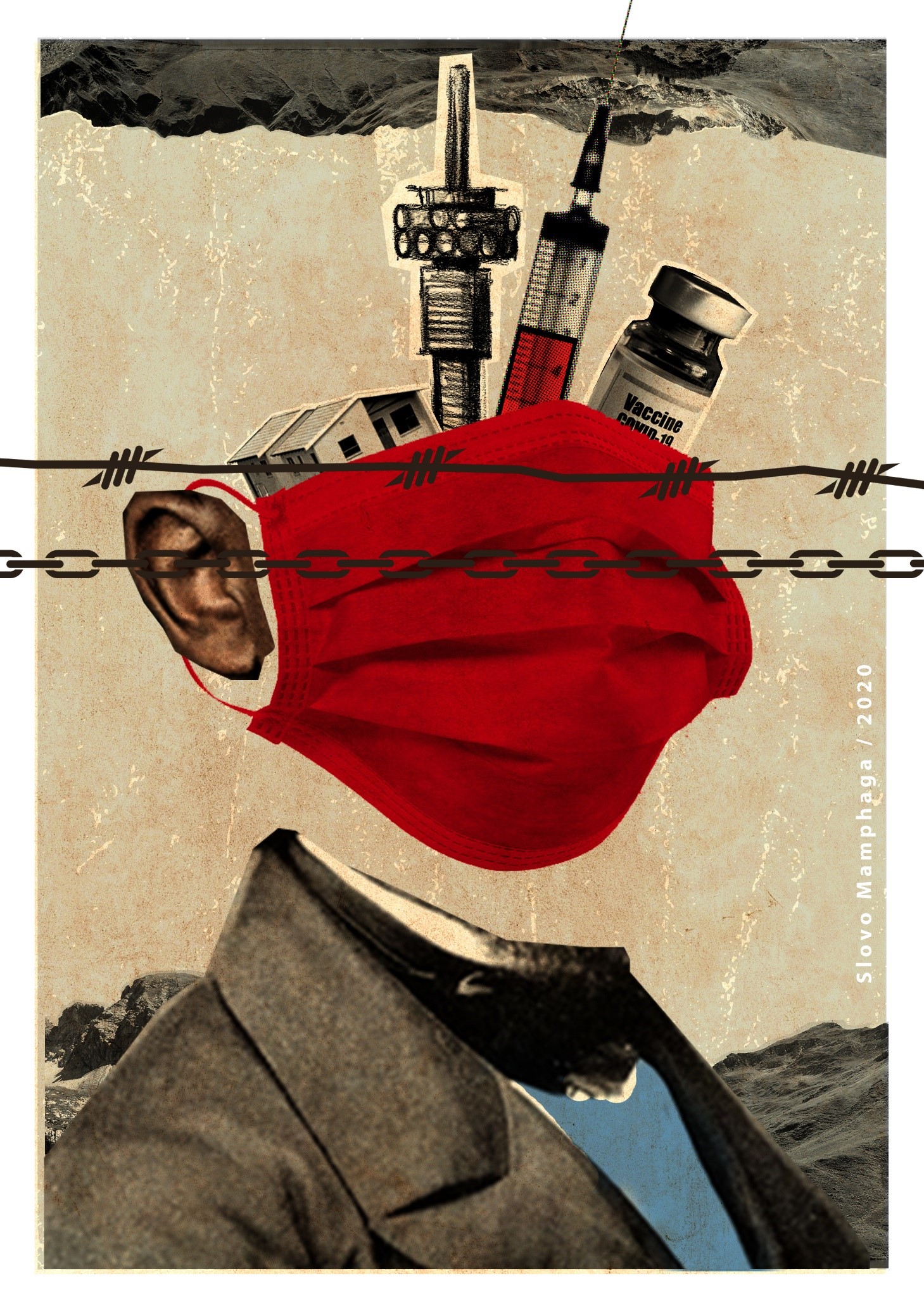

Since this is a course meant to introduce you to politics, and since we learnt at the beginning of the year that modern disciplinary knowledge is always backed by power, it would be irresponsible of us to pretend as if there aren’t political questions thrown up by the university’s decision to turn to distance learning – online learning if you prefer. With many of you supporting the decision, your university formally decided, a little over two weeks ago, to turn itself into a distance learning institution – online learning if that is more palatable to bourgeois sensibilities – as a response to the ongoing pandemic. We have learnt from the history of diseases that because a pandemic leads to unprecedented numbers of mortality, and do not allow for any member of society to be neither affected nor infected – they are rare moments when a societal response is called for. More precisely, because in a pandemic your health as an individual depends on the health of the next person, meaning the more people fall ill in society the greater the likelihood that larger numbers are also inexorably bound to fall ill (and possibly die together with them). For once, we are reminded how as human beings our fate is bound together, irrespective of race or material wealth. And so, such pestilences, pandemics, are a call for the human spirit to act with common purpose if they are to triumph – as Camus teaches us in his seminal text The Plague. Not philanthropy, but the human spirit. The difference is that philanthropy means giving up what you can in any case do without – what you have in excess. The triumph of the human spirit means pulling into the commonwealth all our resources and goodwill, and re-directing them to the benefit and survival of all.

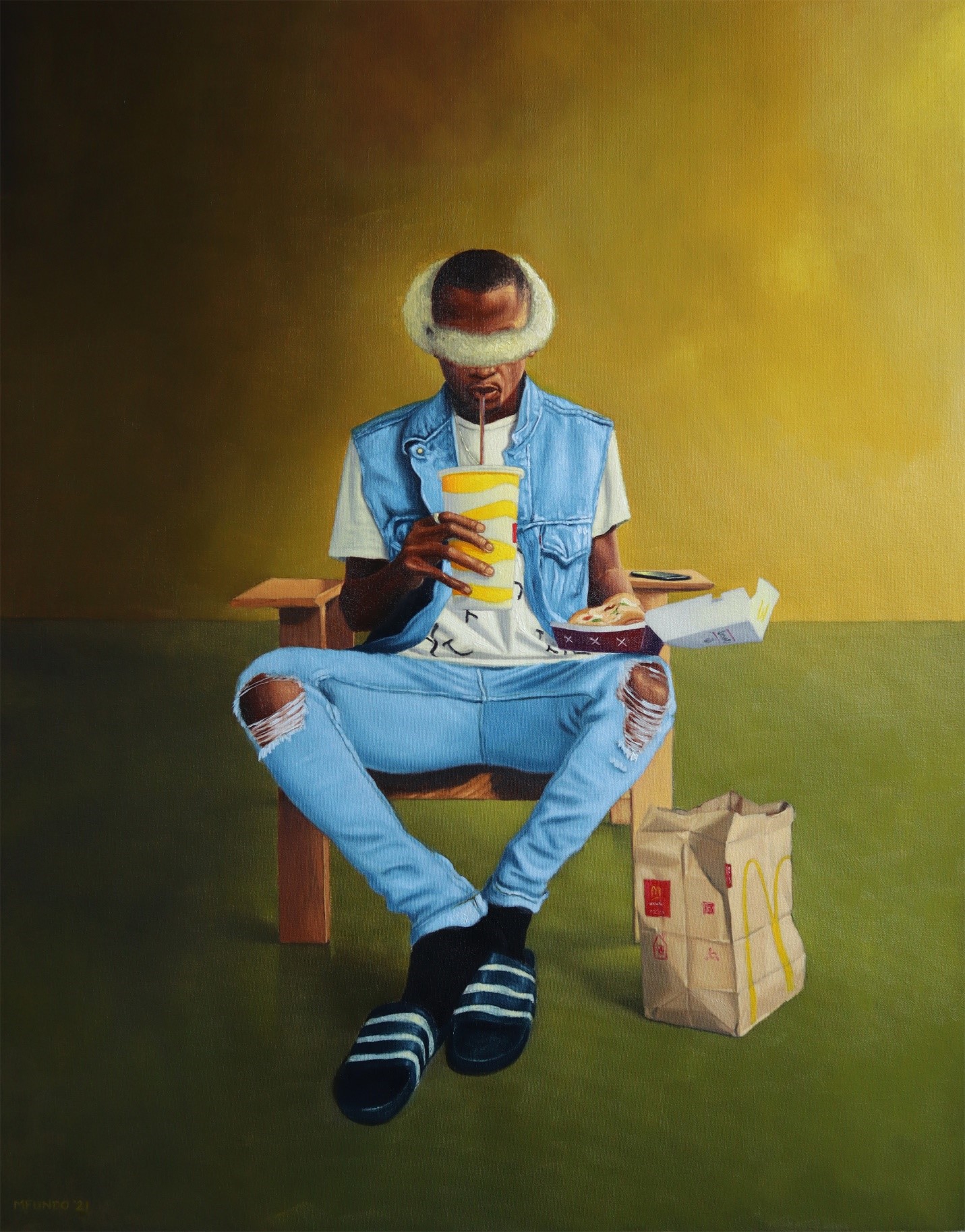

But alas, in South Africa the response to the Covid-19 pandemic has again shown us how, in our societal ethos, racial and economic considerations must always trump the human spirit. It was first the white institutions – with UCT in the lead – that for reasons of racism are better endowed materially, who promoted online learning as a solution. white support, corporate support if you prefer, in the form of donations to make this possible, soon followed (in generous quantities). UCT, in typically patronising liberal language, prefaced its every statement on the switch to online learning by acknowledging that this may disadvantage students who come from poor socio-economic backgrounds’… such that every effort, the institution promised, would be made to be as inclusive as possible. But UCT did not ask why it is that all the students who are poor are Black? Neither did it ponder how hollow its declared aspiration to be inclusive is when, twenty-five years after liberation, the university still has a hall of residence named Jan Smuts? Inclusivity is not computer handouts to poor/Black students, meals for poor/Black students, or whatever else you give to them because they are poor/Black – that is philanthropy. The problem with such charitable philanthropy is that the philanthropists must first create the problem, manufacture people as poor/Black, and then proceed to ‘give’ out things – to soothe their own consciences. Invariably, the philanthropists do not want to see the problem of structurally deprived and oppressed constituencies attended to once and for all – because that is its own condition of possibility. Otherwise, to whom will they give, if the poor/Black no longer exists? The necessity for, indeed the concept of this guilt-cleansing philanthropy, will itself cease to have meaning.

Just in case you are beginning to wonder what all this has to do with online learning, the question must be asked: Why was there such generosity on the part of corporate (read white South Africa) to support UCT’s switch to online learning? I am going to hazard the answer. It was nothing but white South Africa buying itself cultural distinction and a mark of exception, which in future will be exchangeable as political and social capital. What horizon of meaning are we gesturing towards here? It was so that, when the many Black students, who for reasons of being Black and poor attend Black universities, in future rue the fact that they lost an academic year as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, white students primarily would have been saved from such a grim possibility. Black students and Black academics, whose presence is tolerated in these white institutions, failed to apprehend the moment as most opportune to teach white South Africa the full meaning of sacrifice, and the triumph of the human spirit. All it would have taken is for us as Black academics and students to pose the question: How ethically correct is it for us to continue with our academic year as UCT (and other white universities) when we know that the universities of Zululand and Fort Hare, Walter Sisulu University, the University of Limpopo, Mpumalanga University and the University of the Western Cape, etc. will not be able to transition towards online learning? Perhaps it could be that we also wanted to share in that white cultural distinction and mark of exception lent to us by virtue of being in these white universities... Or have we ceased to have any feeling of fellowship, and moral and ethical responsibility, towards those who, like us, are Black and poor but (to rub salt into the wound) attend Black universities?

I will in a moment suggest what ought to have been done – for those minds always demanding answers to problems they do not sufficiently understand. One point needs to be made, first. Will Black students at UCT and other white universities profit equally from the social capital that will flow to white students, from this mark of exception they have bought into? Again, I am going to hazard the answer. It has to be an emphatic NO! Distance learning requires not just the access to a computer and data. It requires several other resources. It requires an environment wherein the student can always have a quiet space/room to retreat to, and the ability to free oneself from household chores and have someone else perform them for you. But here is the most decisive factor – most exams are now going to be substituted by long essays or assignments requiring, at times, texts/resources that are not available online. For the rich the solution to this is simple – order them online and have them delivered. Even when they are available online, we know it is near impossible to read attentively for very long, on a laptop or computer screen. Again, for the urban/rich, a printer in the house or a PostNet down the road are no-brainers. Cumulatively, what all of this means is that, when post-graduate admissions are made in 2021, white students are going to be having a massive advantage. The majority (all white universities are going online) of Black universities remain closed. Consequently, white students will relatively have better marks, because for them the environment for online learning was always conducive, with all necessary resources within reach. All of this in an environment where white institutions, even under normal circumstances, are always less willing to admit Black South African students (they would rather spend their energy on nurturing the myth about them being lazy). Only then, in 2021, are we going to ask why post-grad classes or specialisation programs are predominantly white, with a diminished Black South African presence? Or in 2025, a Minister of Education will ask why universities are producing such few Black South African PhDs – and think he/she has asked an important question...

But the consequences are not only in the future – they are discernible in the present. Anyone who has watched with a keen eye the reportage on Covid-19 in the South African media would not have failed to notice that, every time expert opinion is sought, its personification is always anything but Black. I am yet to see, on TV, a Black South African Professor of Infectious Diseases, Black South African Professor of Epidemiology, Black South African Professor of Health Economics, Back South African Professor of Family Medicine, or Black South African specialist in Medical Humanities. Each time we appear, it must always be as victims, the poor, hungry and filthy looking – crowded in dirty slums called ‘locations’. A logical question we ought to ask ourselves is, where are those other Black people who came to UCT long before us, and like us had hoped to profit from the social capital that studying at UCT offers? Why do they not appear on TV as Professors of Infectious Diseases, to enlighten and inspire their own people? I am happy again to hazard an answer. They never made it. And like them, we are never going to make it. The problem is structural; it does not matter how hard we mislead each other about the possibilities opening before us just because we are at UCT or any other white institution. Exceptions are not evidence of Black people’s progress. Rather, they are evidence of our exclusion. We must abhor them. Why, in a country where we make up 86% of the population, should any serious-minded person revel in being the ‘first Black’ professor, of anything? In 2020?

So then, what ought to have happened, you might well ask? Close all universities and mobilise their residences as quarantine sites, or repurpose them into temporary hospitals. Repurpose their laboratories for testing. Enroll all advanced undergraduate and postgraduate science students into an aggressive testing brigade (of course after skilling them). Enroll all advanced non-clinical medical students, and advanced humanities undergrad and postgrad students in an aggressive, massive community education and screening initiative. Mobilise students and academics in different fields of knowledge to lend their skills, in an inclusive societal response to the pandemic. Foster a spirit of service and of sacrifice. Redirect the budget meant for all universities – to this massive social programme. This is called social mobilisation. But for this to happen, something else first has to be done: the elevation of the preservation and perpetuation of life, all human life, to an overarching metaphysic of society that supersedes economic reason and rationality. The benefit for South Africa at the end of such a project would have surpassed any margin of economic recovery – the gains would have reverberated throughout our past, present and future. Centuries after now, a story would be told of our generation that catalysed the emergence of a new spirit of sacrifice, and ultimately laid the foundation for a united society – where the human spirit and a common purpose and goodwill reign supreme. That would certainly be a much better future, a much better society, than the racist, anti-Black ‘non-racial’ society of today.

I Remain

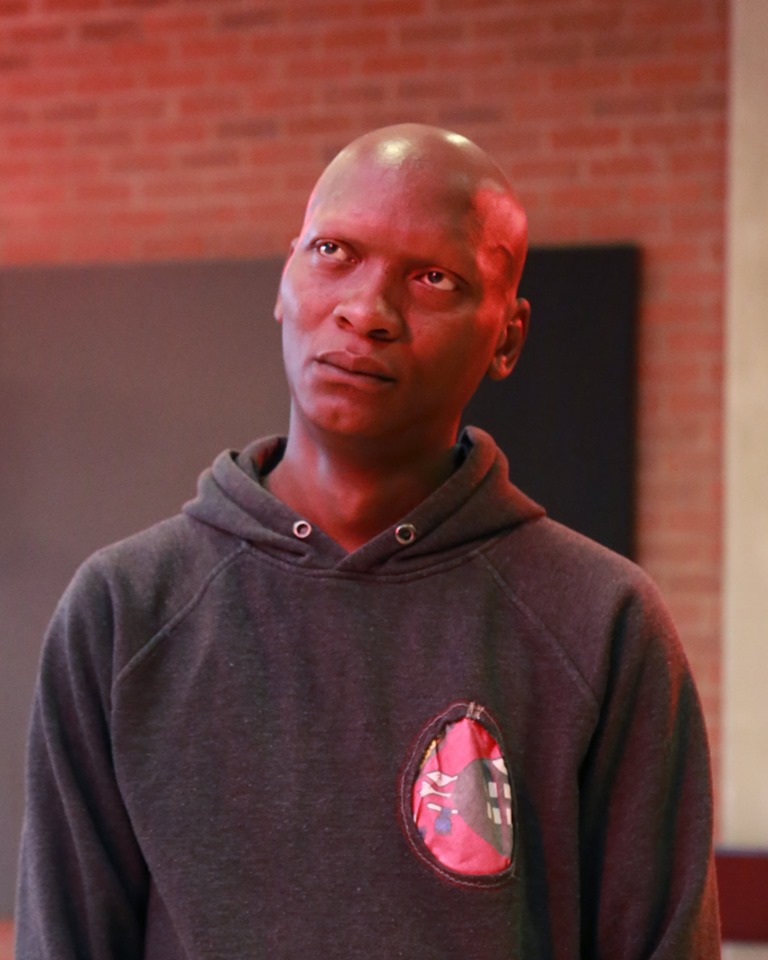

Commandante Lushaba