The state of all institutions is traceable to the origin and evolution of the institutions. The state of democracy in “South Africa” is no exception in this regard. There are two ways to account for the state of democracy in “South Africa”. The first one is historico-conceptual analysis while the second one is the pragmatic analysis. With regard to historico-conceptual analysis the fundamental point is to explicate how democracy came into being, who brought into being and whose interest it serves. This analysis entails what we can designate the genealogical method which we will follow in this essay.

The pragmatic analysis of democracy is premised among other things on the politics of efficiency which currently entails the enumeration of the litany of vices such as rampant corruption and paucity of service delivery. This pragmatic analysis is premised on the empirical method. The central thesis in this essay in line with the genealogical method is that democracy in “South Africa” arose out of a conquest in the unjust wars of colonisation since 1652. This is because “South Africa” itself is a product of this conquest. Thus, South African democracy is an extension of the “right of conquest” by the European conquerors and their successors in title to conquest. This implies that South African democracy as far as the Indigenous people conquered in the unjust wars of colonisation are concerned is not “our” democracy but the democracy of white settlers who brought into being following conquest and whose interests it serves.

Azania as part of African civilization and culture had its own form of democracy which is designated as consensus democracy. In terms of the political philosophy of Ubuntu this Azanian consensus democracy is epitomised by the idea that “Kgosi ke Kgosi ka batho” roughly translating into a king is a king through the consent of the people. This underlies the significance of popular sovereignty as fundamental to Azanian consensus democracy. This is the democracy that the Indigenous people practiced before the catastrophic coming of the Europeans and proudly called “our democracy”.

South African democracy on the other hand traces its origin to European politics and culture which were imposed on the Indigenous people “in the wake” of conquest in the unjust wars of colonisation since 1652. Following Dyadic dialectics which is premised on a mutually exclusive antagonism we postulate that there is an irreconcilable antagonism between Azanian consensus democracy and South African democracy. South African democracy which is based on the “right of conquest” traces its formal origin to the 1853 constitution which was premised on a nonracial franchise. This constitution accommodated the Indigenous conquered people who accepted “the terms of order” of white settler colonialism for instance by voting in the Cape colony. This constitution as part of the overall “civilizing mission” of white settler colonialism only accommodated the Indigenous conquered people who were called “civilized natives”. These are the Indigenous conquered people who internalised the norms and values within the settler colonial sphere.

In so doing these “civilized natives” pursued “actual being” in the sense of seeking to transform the white settler world and to live among white settlers. They embraced what Rhodes called “equal rights for all civilized men”. It is in this sense that we can posit that constitutionalism and democracy in South Africa are a conquest-based racist project of “civilizing mission” spearheaded by the liberal white settlers as the so-called “friends of the natives”. The “civilized natives” who were “befriended” by these liberal white settlers were called “amakholwa” the products of the cultural warfare of white settler colonialism called christianity as spearheaded by white missionaries who were later succeeded by white liberals.

It is important to note that civilization is one of the elements of the doctrine of Discovery central to conquest since 1652. From the 1853 Cape constitution South African constitutionalism acquired its reconfigured form with the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910 based on the conquered territory of the Indigenous conquered people. Within the Union of South Africa, South African democracy was premised on the Union Act of 1909 which excluded the Indigenous conquered people, even the “civilized natives”. This is because the Union of South Africa, following the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging was premised on “exclusive South Africanism” in the name of South Africa being a “Whiteman’s land”.

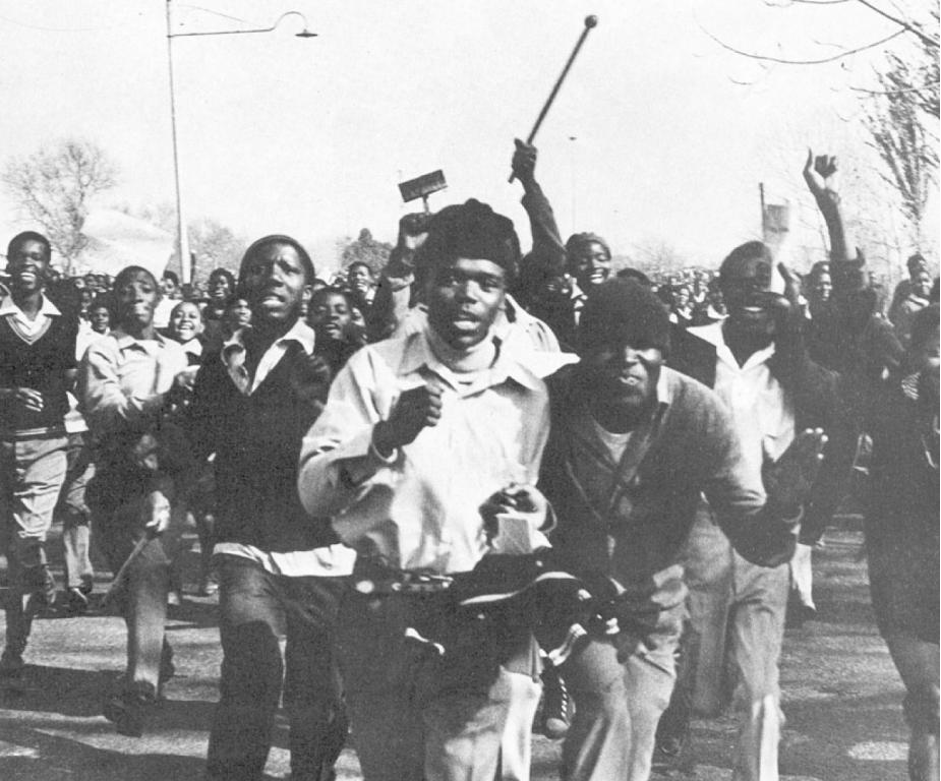

It is in this sense that we can state that with exclusive South Africanism (an expression of white nationalism) as orchestrated by the likes of Smuts, “South Africa belongs to whites who live in it”. The “civilized natives” wo felt alienated by this exclusive South Africanism resorted to petitions to appeal to the “imperialistic conscience” of the British Empire to be included in the Union of South Africa. They commenced through the South African Native Congress around the time of the formation of the Union of South Africa and triumphed as the African National Congress in 1955 with the adoption of the so-called Freedom Charter.

It was on the basis of the “Freedom Charter” that the “civilized natives” called for an “inclusive South Africanism” (an expression of multiracial/nonracial nationalism) as per the logic of the democratization paradigm. Fundamental to this inclusive South Africanism is the idea that “South Africa belongs to all who live it…” Thus, in terms of Triadic dialectics which is premised on the telos of a higher synthesis in the Hegelian sense, exclusive South Africanism is a thesis, inclusive South Africanism is the antithesis, and the synthesis is the nonracial post-apartheid democracy which under the illusion of the “Rainbow nation” is regarded as “our democracy”. This higher synthesis of the civil rights movement led by the African National Congress epitomises the triumph of the democratisation paradigm since 1994. It is also responsible for the historical fiction of the 1994 moment as representing the “first democracy and democratic elections” thus “our democracy”.

The formalized inclusive South Africanism since the adoption of the “Kliptown Charter” reaches its apex of formal expression in the Preamble to the final constitution in the form of “we the people of South Africa…” This is the same constitution which for the first time in South African constitutionalism and democracy inaugurates the principle of constitutional supremacy and the constitutional court just when the Indigenous conquered people, not just the “civilized natives” form part of South African parliament. The principle of constitutional supremacy of course vitiates popular sovereignty as it undermines the numerical power of the Indigenous conquered people by endowing the constitutional court through the doctrine of judicial review, with the power to override the Legislature in terms of creating and passing laws. The necessary coincidence of the coming to parliament of the Indigenous conquered people and the principle of constitutional supremacy and constitutional court are reflective of “native problem” or “swaart gevaar”.

The latter is a classic white settler anxiety of being overpowered by the African majority thus undermining white supremacy in South Africa. This underlies our thesis in terms of the genealogical method that South African democracy mistakenly called “our democracy” by the Indigenous conquered people was brought into being by white settlers to serve their interests in line with white supremacy. It is through post-apartheid South African constitutionalism and democracy that white settlers choose to ensure their survival as a race and cultural group in South Africa.

South African constitutionalism since its inception in 1853 was premised on white settler popular sovereignty thus compatible with “democracy as understood in the West”. This implies that since 1853 South African constitutionalism and democracy have been “familiar bedfellows”. They only became “strange bedfellows” since 1994 with the constitutional court and the principle of constitutional supremacy. This state of the so-called “our democracy” calls for the resurgence of the decolonisation paradigm. This paradigm unlike the democratisation paradigm which pursued inclusion on the basis of the extension of civil rights to the Indigenous conquered people, pursues the restoration of sovereign title to territory to its rightful owners and the rebirth of Azanian consensus democracy.

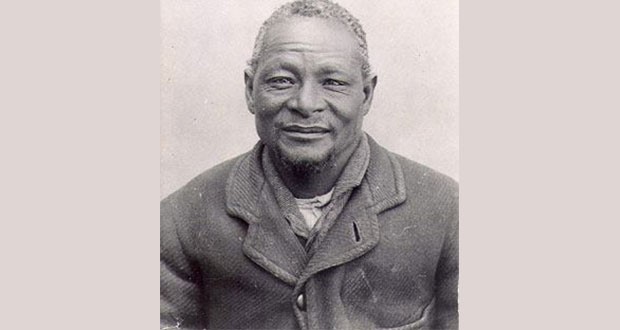

The decolonisation paradigm is in line with the pursuit of “historical being” in the sense of destroying the white settler world. It is premised on the antagonism between the native and settler and Africanism ala Africa for the Africans. Its pioneers are Amaqaba who refused Christianity and remained loyal to the native sphere. It found its highest expression in Nongawuse, the Ethiopian movement, the Garvey movement, the Wellington movement, the Israelite movement and Poqo of the 1960s. Following this liberation tradition, we posit that the Indigenous conquered people have to abolish the so-called “our constitution and our democracy” as the two pillars of South Africanism and destroy South Africa itself through Chimurenga as a liberation war. In its place restore post-conquest Azania on the basis of Africa for the Africans thus, Europe for the Europeans and Asia/India for the Asians/Indians, after expelling in the violent process of the reconquest of Azania all non-Africans, namely the Eurasians/Europeans and Asians/Indians.