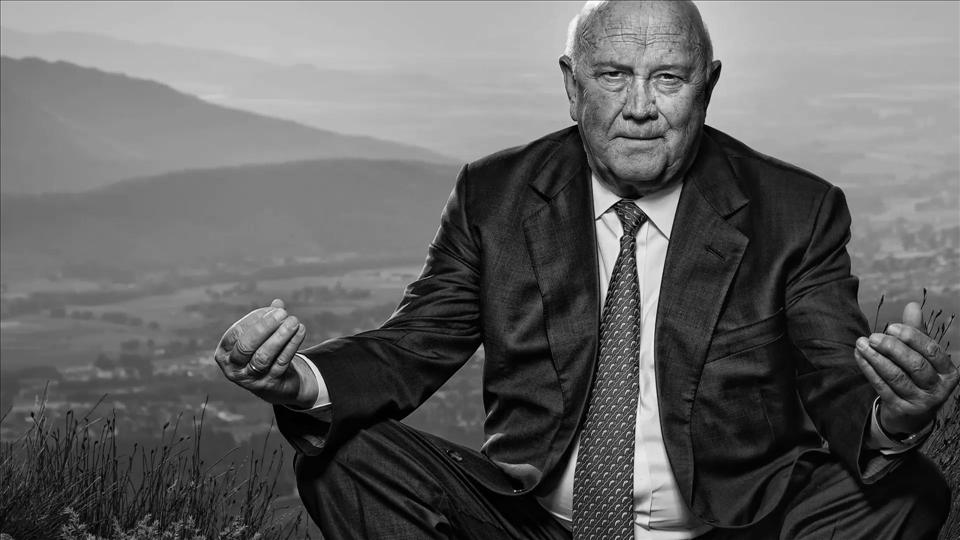

The thrilling theatre production titled ‘Red On the Rainbow’ written and directed by Monageng Motshabi makes it notable that race and culture are intimately interwoven. After all, culture is not only a product of race but also a form of a process of adaptation to a particular environment. Throughout history, we have come to know of four races which have been culturally distinguished by their environment. These are the African, European, Asian & American races. For this production, Motshabi has chosen to focus on two distinct cultures and races; the African and the European. The choice was based on a traumatic event which took place in the North West of South Africa in 2017. On the particular date, two men of European descent brutally murdered a boy of African descent apparently after having caught him attempting to ‘steal’ sunflower seeds on ‘their’ farm.

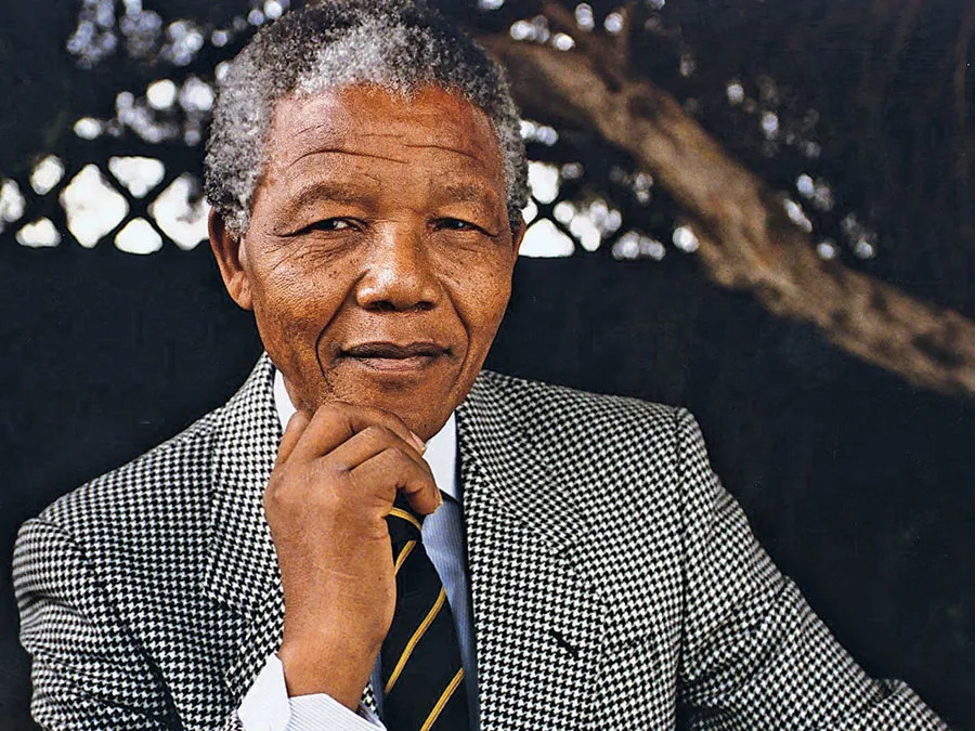

Although the case has been repeatedly labelled as one of racism, I found it more pressing to analytically review the play as a case of cultural confusion within the people of African descent just as the play has done. This is not to imply that racism is an exhausted concern in South Africa; some may even argue that racism is intrinsic in the country’s social, historical and political formation. It is rather to prioritise the restoration of the cultural identity of African people and as a result, end the perpetual state of injustice in the country as seen on Red on The Rainbow.

Upon seeing the title, it is almost instinctive for the potential audience to ask; why has red been singled out in the South African rainbow – of all the colours, is it because red represents blood? In watching the play, it was made clear that instead of the rainbow representing racial colours; it represented a marker of the 1994 democratic transition of South Africa –a “timestamp”. Red, although is said to symbolise the blood that has been lost by African people throughout their struggle for liberation is highlighted in the title to symbolise the blood that the people of African descent continue to shed – even after the “timestamp”. Contrary to European cultural understanding of time which is linear, African time is both cyclical and linear. There is sacred time and profane time which are intertwined in their operation. This differs from Europeans who possess an either-or form of logic with regard to all that is within their existence, including time. Time for the African can never be limited to linearity because similar to the cycles of the universe which exhibit change, the African spirit never dies; whether peaceful or restless. Instead, it regenerates through a new body and continues the cycle.

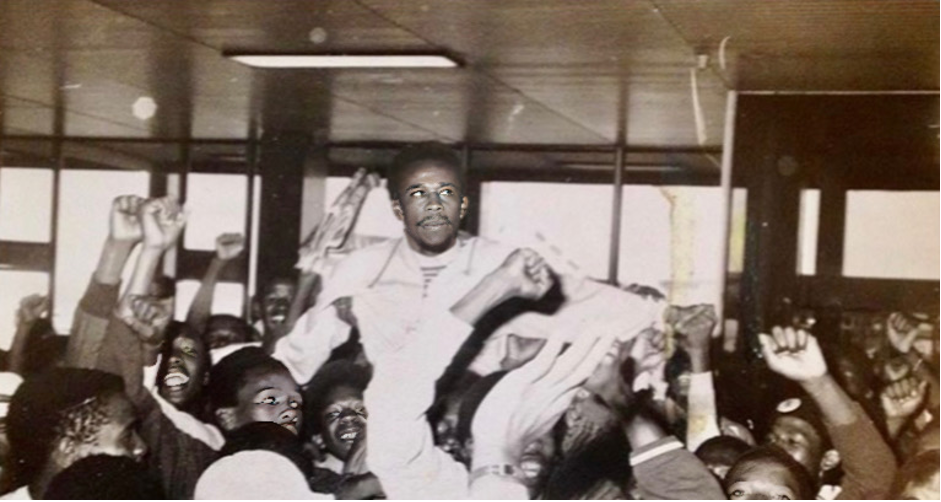

Traumatic as it may be, the African nation has to begin to reflect on the number of restless spirits that have regenerated in new bodies; in which their old were forcibly separated from their spirit under white settler colonialism, imperialism and the so-called post-apartheid democratic South Africa. If the spirits are not well rested, the chaos and the trauma of historical interaction between Africans and Europeans history will continue to haunt the new generations of the people of African descent just as we witness the brutal murder of the African child in the play. There seems to be no ending of the disaster that has been faced by Africans across the globe, but a repetition. This is because there has not been any growth of the spirits from their historical conditions since the duty of attaining justice still awaits the same spirits that are now within us. In another case, European existence which continues on linear time has its historical foundations of self-destruction and exceptionally, African destruction. There could never be any change nor development throughout their existence that excuses African people from fulfilling their ancestral mission.

The play refuses to hold back on exhibiting the destruction of African culture that has been brought by the cruel historical interaction between Africans and Europeans, amongst other destructions. It should be of no surprise that European culture is shown within an African context and is represented by a person of African descent. This is evidence of the writer’s consideration of the centuries of the Maafa within which the practice of African culture was forbidden. We have intentionally avoided to use the word ‘illegal’ since any African would know, that in European culture the terms ‘morality’ and ‘legality’ are mutually exclusive. The non-African law is characterised by barbarism due to a lack of a moral instinct –this is the fundament that makes the two cultures eternally antagonistic. For centuries, Africans who had interacted with non-Africans had been forced to adopt foreign culture and furthermore bring it into their homes. The African cultural destruction in the play is actively narrated through events that take place after the murder of the child. Suddenly, there is a cultural clash within the family which should have initially been united by similar cultural values. However, the de-Africanisation of the father through European cultural integration has plunged him into a feud with his African culturally grounded wife who tries by all means to maintain, or rather restore her African culture as she knows it.

Although in African culture it is of importance that during a loss of a family member peace should be retained at all times, the father never misses a moment to fight his wife against her wish to fetch the spirit of their son from the farm on which he was murdered as per the cultural practice of African people. He further disregards the importance of his son’s spirit by mentioning that the murder of the son was good riddance since he was a victim of a drug known as nyaope. This, according to him, exempts him from fulfilling his role as an African father by not supporting his son’s journey toward rehabilitation either mentally, physically or emotionally. He chooses to follow the Euro-Capitalistic logic that if there is no value that an individual is bringing in terms of profit, they are worthless. The Euro-vision he has chosen to adopt in the name of ‘civilisation’ has led him to regard his son as a deviation from the supposed norm of society. This is rather not surprising since Euro-logic operates on the basis of individualism and this disables him from discerning that the usage of the drug is not only a communal problem, but a national one. This logic further paralyses his critical thinking abilities and he is therefore unable to conclude that even after democracy, townships remain enslaved, this time through drug usage. As if dismissing his son’s life and spirit was not enough, the father substantiates his stance by stating that his Christian god rejects African customs because they are demonic in nature. All this is done under his authority as a man in an inherently patriarchal non-African culture…

Had he been well grounded in African culture, he would know that his real culture is inherently matri-focal. It is important to note that matriarchy is not the same as matri-focality. Unlike Europeans, Africans are not obsessed with the dominance of one group over the other. In African male and female relations, no group is required to dominate another. Confusion only remains within African families which, like the father in this play, have adopted a European identity, personality and culture within their own. The matri-focality in African culture centres and honours females as the beginning of human life since in Afro-logic; life comes from the womb of a female and not the rib of a male. Furthermore, females in African culture, are understood to be more spiritual and instinctive due to them possessing the ability to carry and nurture another life and spirit within them. This is not to say, like the Euro-centrically liberated women do, that the purpose of a woman is limited to reproduction. Instead, it is to say that just by being female, one is inherently spiritually advanced, possesses natural adaptability and inner wisdom–whether they choose to have a child or not. In the African world sense, value is not limited to all that is material. The difference between the two sexes is not for one to dominate the other but to first, balance the male and female principles within them as individuals and thereafter balance their external differences in relation to the opposite sex. This differs from European culture, in which the man dominates the woman on the basis that she is naturally evil, unwise and dirty –spiritually, emotionally and physically. As a result, the value of women is solely reproduction. To this day, women remain barred from particular duties and cannot lead in places reserved for the rational and powerful gender, the man. The mother in Red on the Rainbow, undented by European logic and culture, fulfilled her role as an African, stood up for the life and spirit of her son and retained African culture.

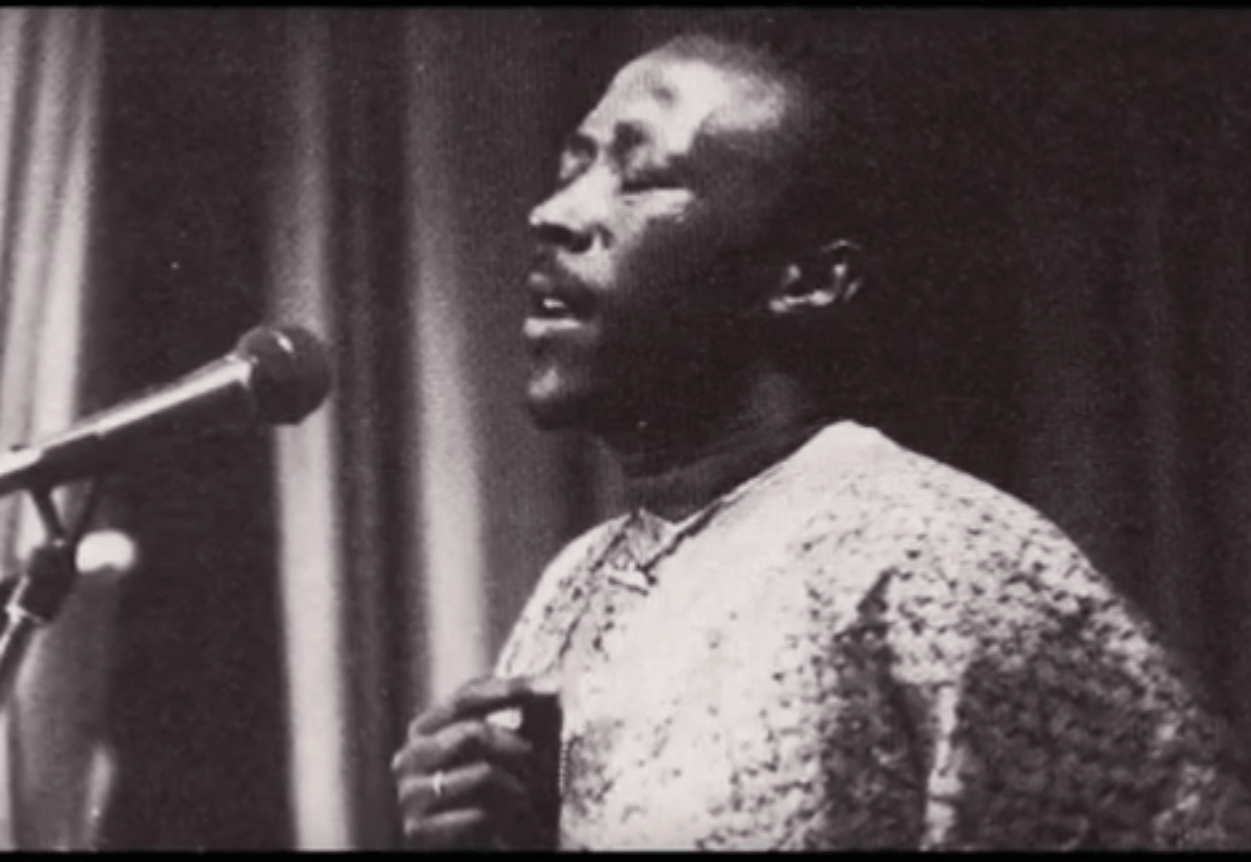

Finally, the African culturally grounded mother sought to ensure that the spirit of his son rests in peace despite her son’s brutal murder which took place on African soil at the hands of the Europeans. The manner in which she chose to confront tragedy is informed by an African proverb ‘Ityala ali boli’ translating to; ‘an unjust act never expires despite the passage of time.’ Logically, events that are to take place after an unjust act could only be a continuation of injustice, not a correction. The evidence lies in our current living conditions in the now ‘Rainbow’ land. These conditions which are characterised by the endless acts of injustice are a continuous attempt by the European perpetrators to limit the probability of Africans to answer the long-standing ancestral call of attaining justice and acting toward restoration. In the play, African culture is shown to prioritise the notion of ‘an eye for an eye’ as a way of restoring balance following the reign of evil. There could be no better sacred message passed from our ancestors to the current and future generations than what the play has shared. Red on the Rainbow has demonstrated to us as Africans that war continues because justice isn’t served. This war which was initiated by the Europeans should be ended by Africans through a form of a counter war of restoration and regeneration of Africa.

The play will be staged at the South African State Theatre from the 7th of March 2022 till the 27th of March 2022.