During my self-induced seclusion from social media engagements, I conducted some research about the historicity of the plateau known as the City of Polokwane (previously Pietersburg).

It is during this forlorn sojourn that I reviewed the report I had previously penned for the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights, about the Black Warrior called Kgoshi Maraba Ledwaba I of the Mashashane Tribe – "an offshoot of the Ndebele nation under Kekana", descendants of Musi.

In the report, I spoke of the sprawling Black settlement called Marabastad (Maraba City) which stretched from the farm Dalmada, near Savanna Mall, to the farm Holland, which adjoins the Ranch Hotel. The settlement dates back to the late 1800.

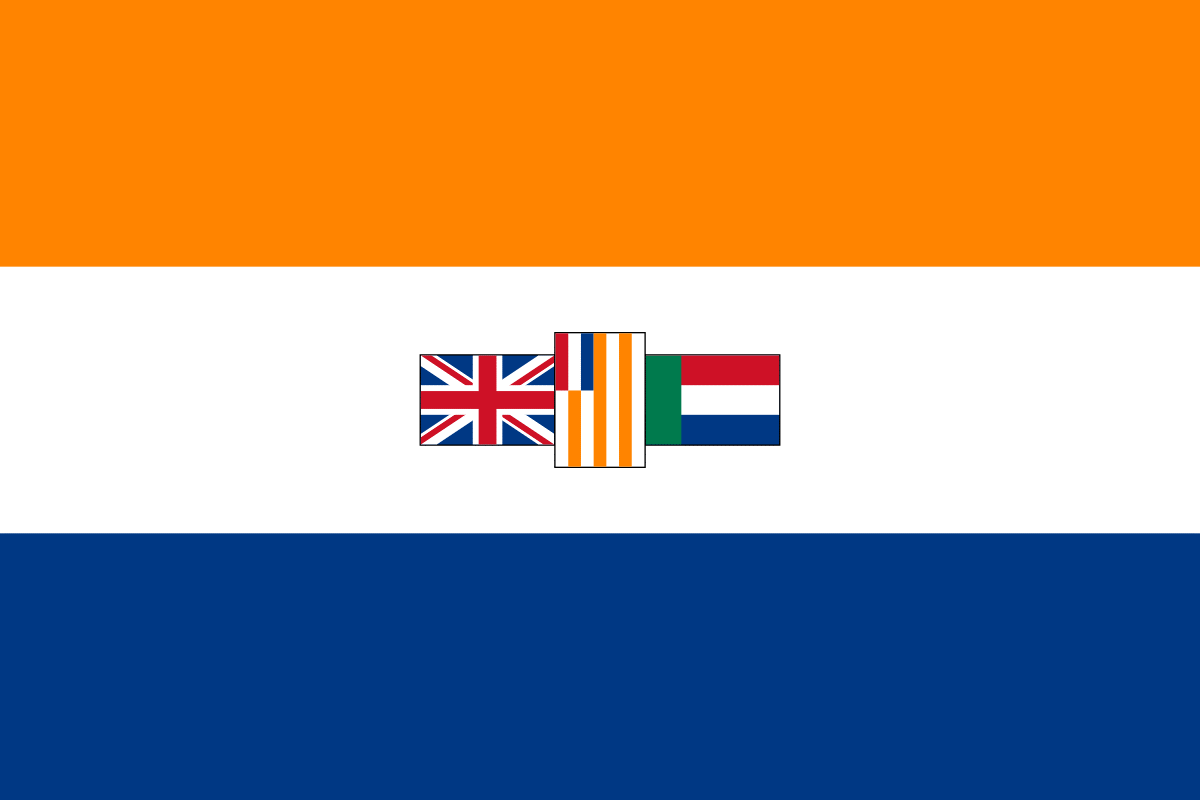

Voortrekkers’ invasion of this pristine indigenous land of our people coincided with the discovery of gold deposits near the farm Roodepoort, which resulted in the area being renamed Eestegoud, Afrikaans for “First Gold”. It is understood to be the first gold mine in Southern Africa, which precedes even Johannesburg.

Contrary to popular belief, Polokwane does not mean a ‘place of safety’ – as we've been force-fed. There is no local language or dialect; Isindebele, TshiVenda, XiTsonga, Sepedi, Tlokwa or KeLovedu included – which defines “Polokwane” as a place of safety. Unless they meant to say “Polokano” – which perhaps could remotely be an aphorism for some form of camaraderie – looking after each other; to bring about much vaunted yet elusive social cohesion.

Legend has it that the real story behind the name is that the Zuid Afrikaanse Republic (ZAR) sent Voortrekkers to hunt down and kill Kgoshi Maraba Ledwaba I, as he had been mounting resistance against settler occupation of his territory. Whilst on his trail, these hitmen came across three beautiful Ndebele maids who had gone to fetch water by the river, and had settled on the river bank to make necklaces out of beads.

Pretending to be fascinated with their skills, the bounty hunters enquired what the maids were doing. In deep Ndebele, the girls retorted, "Si luga Ubhulungwani ka Maraba". That's when the bounty hunters knew that Kgoshi Maraba Ledwaba I was nearby, and accessible to these maids. They then secretly followed the maids to the Royal Kraal.

As they could not pronounce "Ubhulungwani", the Voortrekkers went back to the military camp to report the encounter with the maids to their Generals – that the area belongs to Kgoshi Polokwane ka Maraba – corrupted version of Ubhulungwani ka Maraba. This version of events was confirmed by Makgoshi Mokgaetji Ledwaba II of the Mashashane Tribe. Mashashane is said to have originated from the Pedi words "Seshani sa Basadi".

Shortly after this chance encounter, the war for land dispossession intensified, with further reinforcements from the ZAR regiments.

In a vile, calculated act of extermination, Maraba Ledwaba I and his people were ruthlessly attacked and displaced, and Kgoshi Maraba Ledwaba I was himself beheaded – and his head taken to Pretoria as a bounty trophy.

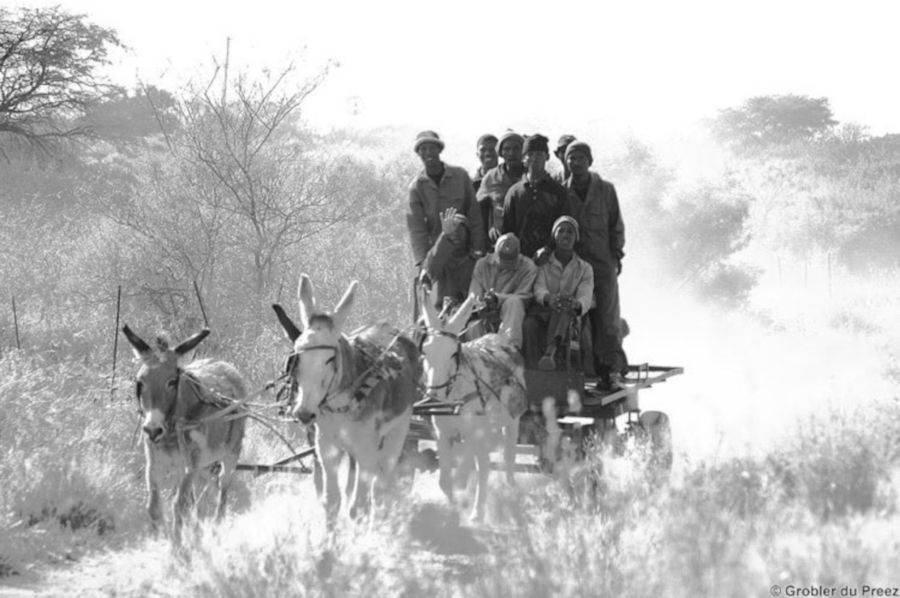

The Vootrekkers came up with a concocted story, that Maraba Ledwaba I had been killed for exceeding the speed limit in his donkey-drawn cart. What utter nonsense!

This warrior was killed for defending the land belonging to his people.

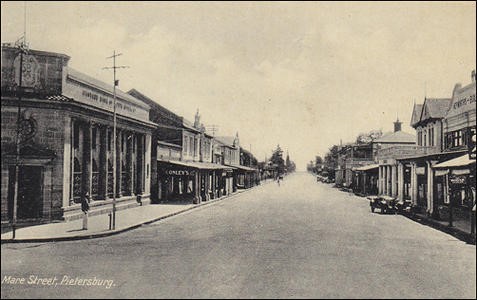

The sprawling City of Maraba was vanquished, and the area was subsequently proclaimed the town of Pietersburg – named after a reverend then known as Pieter Joubert, in 1886. In 1904, Mashashane location was later proclaimed, approximately 36 kilometres to the southwest of Polokwane, across Molaotsi River, on the land of Bahlaloga Ba Moletji – to resettle Maraba's people. In this way, all trace of the existence of the tribe was removed from the history books of Polokwane.

Around 1886, the ZAR enacted the Land Occupations Act No. 8 of 1886.

In pursuance of this legislation, land was expropriated from surrounding Black communities such as the Mothibas of Mothibaskraal, Ledwabas of Marabastad etc... and set aside for occupation by Voortrekkers and Jews from the Soutpansberg area – on condition that they settle there and work as tradesmen for the Gold Crushing Company, and farming enterprises around the area.

The land given under this Act accounts for the disparity in wealth between Blacks and whites in this area.

That's why it is essential for any nation that rises from the vestiges and yoke of colonialism and apartheid, to find itself and to achieve this – utmost care must be exercised in re-tracing and rewriting the history of its people.

The correctly written history will go a long way to healing the nation, dressing the gaping wounds inflicted on its collective psyche, and restoring tenets, ethos, mores and ultimately, the violated dignity of its people.

The continuing legacy of historical revisionism is the antithesis of such a project, and if left unchecked it might result in the infinite distortion of our history – and thereby rob us of our identity and rightful claims as Black people.

The moral of the above story is that the morass we find ourselves in is in some ways self-inflicted.

This brings me neatly to the question; why has it escaped the collective wisdom of the current crop of politicians – to posthumously give recognition to this great warrior ancestor of our people, Kgoshi Maraba Ledwaba I, by naming the City after him? After all, it was entrusted to him by the ancestors – to administer on behalf of his people?

Why are street names and monuments, in and around the so-called City of Polokwane, still bearing the names of our oppressors?

Why are the names of our warrior ancestors, such as Khosi Makhado of the Vhavenda, Queen Modjadji of Balovedu, Kgoshi Mogane of Mapulane, Khosi Mudalahothe and Queen Mantantise of the Batlokwa, Thulare of Marota, Ledwaba I of Mashashane, Kgoshi Kgabo Moloto of Bathaloga Ba Moletjie, Kgoshi Dikgale, Matlala and Mothiba of Bakoni, Kgoshi Makgoba and Molepo of Ditlou and others, not proudly emblazoned in our street names and buildings? Are we a nation of cowards, who have canonised our own oppression?

This piece is deliberately meant to be provocative, and to ignite debate towards the accurate deconstruction and/or reconstruction of our history as a people. Our future depends upon it.