If we want our stories to be told, we must tell them. This is a lesson I experienced while compiling Shimla Park: A Campus Race Struggle. This documentary unpacks the infamous Shimla Park assault of Black workers and students by white rugby supporters at the University of the Free State in February 2016.

I have learned this far more keenly by watching Salt River - The Untold Story , a documentary on an anti-apartheid protest by Salt River High School learners, teachers and parents in September 1976. The response by the apartheid government to these protests was violent, and included the arrest and shooting down of learners.

The narrative of the Soweto Uprising of June 1976 is powerful. However, South Africa must invest more energy into expanding that narrative, to include histories across the country during that same period. This is not to undermine the Soweto protests, but to draw even more attention to how they inspired revolt throughout South Africa.

TELLING THE STORY

One such place that was motivated to resist after witnessing the violent police response to the Soweto Uprising, was Salt River High all the way in Cape Town. Here, many of the students were Coloured and Afrikaans-speaking, but were conscious of the gross injustice language was used to oppress Black South Africans. More than this, they were aware of the far-reaching racial oppression during apartheid.

This is an important narrative on the history of Coloured anti-apartheid activism. Many Coloured South Africans today distance themselves from Blackness which is an affront to the solidarity shown by Coloured South Africans during apartheid. There is also an important conversation to be had on the lack of information spread widely on Coloured history, which has created a void filled by offensive and dehumanising humour attached to Coloured identity. This documentary is one part of an erased Coloured history in South Africa.

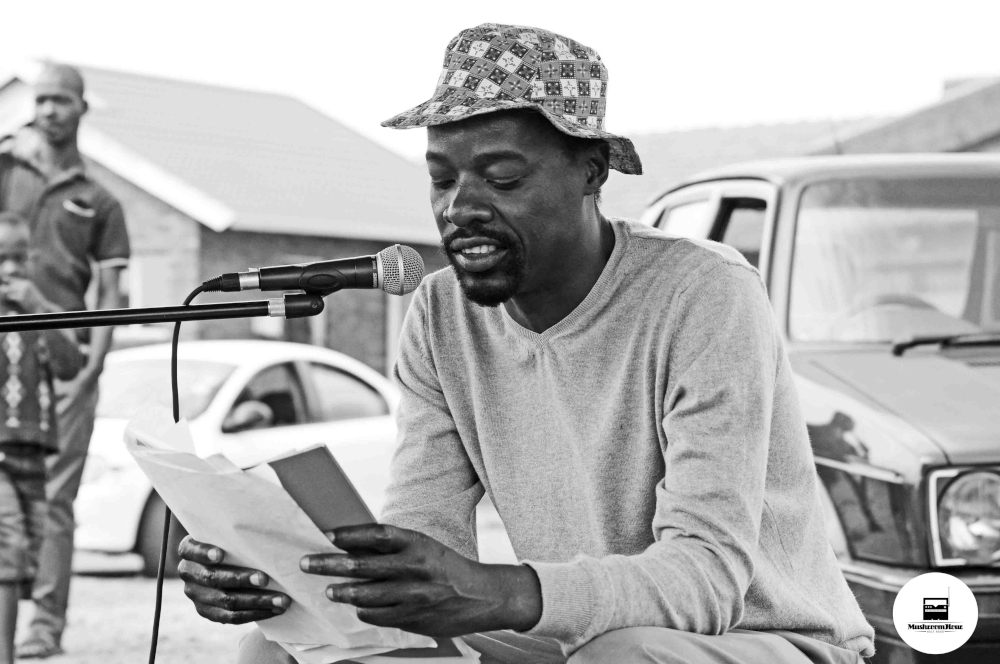

However, there would be no such documentary if one of the students who participated in the protests did not make it. The producer and director, Anwar Omar, was 14 years old at the time and was the youngest of the arrested students. They resolved to march to Parliament, but were prevented by the aparthied police.

“That demonstration targeted Parliament, but never reached there, as it was violently dispersed by the (apartheid era) security police at the (CBD’s) Golden Acre. This is extensively covered in the documentary,” Omar told IOL.

The documentary also explores the death in detention of one of the protesting learners and the discrimination and racial disparity of the justice system.

About a screening within the South African Parliament in 2018, Omar remarked, “this story is making its way to Parliament after all.” Importantly, we must come together and tell our stories. We should not wait for a traditional media company or for any other power.

AN UPRISING YOUTH

Another lesson from the documentary, is the role of school learners in opposing apartheid. Today, school learners continue to protest racial injustice in schools. Young people in South Africa are deeply patronised, underestimated and disenfranchised. Our voices are discounted, ignored and considered naive. In reality, young people are at the forefront of changing socioeconomic norms and fighting injustice against all identities. Still, there is a sense that young people are entitled and unappreciative of the struggles fought by today’s current political guard when they were young. However, what it means to be the next generation is to critically challenge any of the shortcomings of the previous. The youth that follow from us will and should challenge our own shortcomings.

The documentary briefly uncovers the school curriculum and how education was used to justify apartheid through topics such as the “Native Problem”. Apartheid was effectively telling people they were problems in their own country. This was indeed carried through the violent police response to school protests.

We live today in a deeply troubled school environment. History textbooks give too little priority to our stories or give these stories from single perspectives, usually under the ruling ANC narrative. School learners are also heavily enforced by arbitrary rules on appearance and discipline, which are entirely unnecessary to education. The objective is to create a schooling environment where school learners are controlled, unconscious and accept the current conditions of the world.

However, youth are uprising again. University students have organised and continue to become more conscious of injustices within the post-school system stretching into the world. They have started to re-imagine South Africa without oppressive control. School learners have grown the same consciousness. The fear of the older guard is that the next generation of people will create a more just society. Indeed, we have already started to build it. The starting point, however, is to organise and tell our stories.