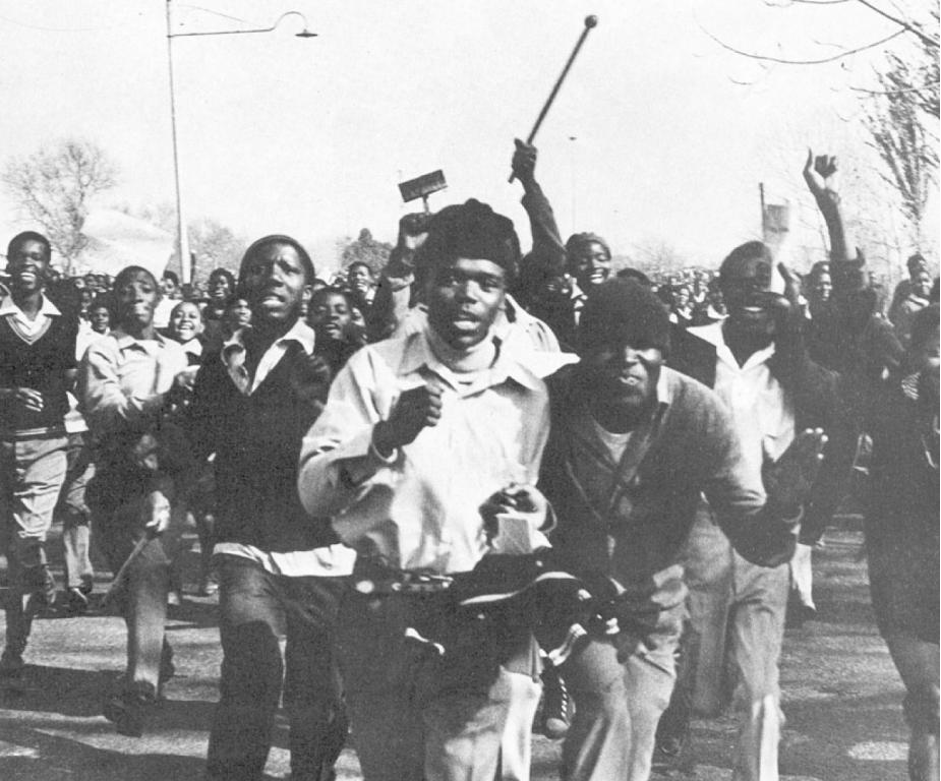

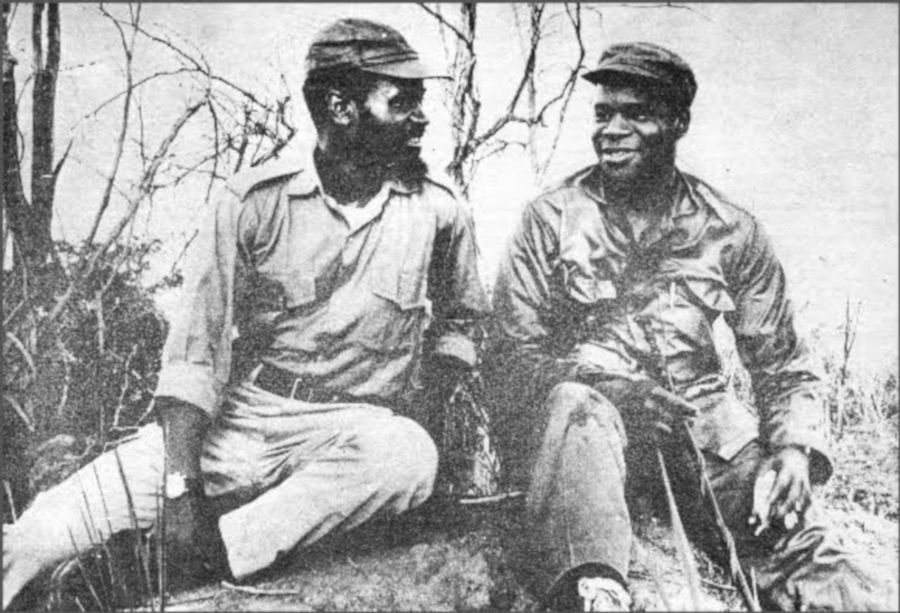

The 27th of January marked the birthday of Tsietsi Mashinini who in terms of South African history and politics symbolises the idea of Black Power. Black Power as embodied by the activists of 1976 was an important challenge to white power as epitomised by the Apartheid regime. The dialectic of Black Power and white power as historical and political antagonists in South African history and politics since the arrival of European conquerors in 1652, reached its apex with the 1976 confrontation. While the movement of Black Power as symbolised by the leadership of Mashinini and his comrade Khotso Seatlholo did not lead to the ultimate defeat of white power, it has contributed significantly to the problem of ideology and political vision in South African politics and history. Ideologically speaking this Black Power movement as spearheaded by Mashinini and Seatlholo with the significant contribution of many Black women, was a continuation of the Azanian political tradition.

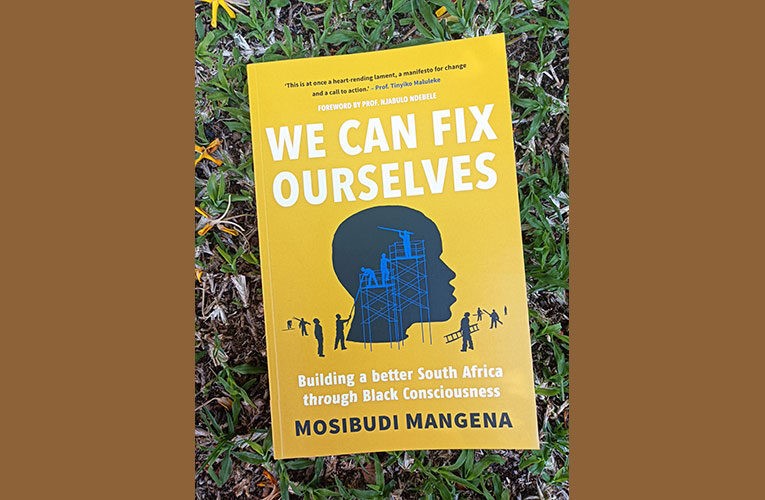

This tradition was pioneered by the adoption of the name Azania in the 1960s by the Pan-Africanist Congress under the leadership of Robert Sobukwe. This famous adoption was made with the view to distinguish the PAC from the ANC and its alliance in the Congress of the People which adopted the Freedom Charter in 1955.In essence these dissimilar adoptions embodied the core of the national question in “South Africa”, namely to whom does the land belong? According to the Azanian tradition of Sobukwe and Steve Biko Azania is the rightful name for the territory now called South Africa and that this territory belongs solely to the Indigenous people. The Congress tradition on the other hand claimed that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white”. The Black Power movement of Mashinini in line with the Azanian tradition rejected the claim of the Congress tradition.

It is in this sense that Black Power and the Azanian political tradition converged in 1976 under the leadership of Mashinini and Seatlholo. While Mashinini was in exile he famously declared that “the ANC is defunct and the PAC is dead”. While the historical context of the 1970s when Mashinini made this declaration may be different, it is interesting to analyse its significance in the so-called post-Apartheid South African context. When Mashinini made this declaration the Apartheid regime had already declared its own war against the liberation movement. The Apartheid regime was neither defunct nor dead. Its military and political power were on full display and viciously applied against the brave efforts of the Indigenous conquered people to resolve the historic injustice of land dispossession and the restoration of the Azanian self-determination and sovereignty. The current historical context is similar and different at the same time. The historical context as far as the Azanian political tradition of Sobukwe and Biko is concerned, is still one of white settler colonialism and white supremacy. The only difference is one of regime rather than structure. The structure remains one of white settler colonialism as characterised by land dispossession and lack of national self-determination and sovereignty of the Indigenous people. The regime is no longer that of Apartheid but of post-Apartheid under the Congress tradition of the ANC. The Azanian tradition of the PAC and BCM lost to the Congress tradition of the ANC in 1994. But what is the position of the PAC and the ANC today as we remember the birth of Mashinini? Can we still argue as Mashinini did in the 1970s that indeed the ANC is defunct and the PAC is dead? As far as the possible attainment of political power in parliament to implement the political vision of the Azanian tradition of Sobukwe and Biko, we can confidently agree with Mashinini that the PAC is as good as dead. This is in spite of its formal existence in parliament. The only time when the fire of the Azanian tradition was kept alive was with the Rhodes-must-fall movement in Cape Town. Ironically this is the same Cape Town that under white settler colonialism is pursuing independence today. This is in contradiction to the Azanian tradition’s vision of integrating white settlers into the African majority and democracy on the terms of the Africans as a cultural and numerical majority.

While I disagree with this vision (aligning myself with Anton Lembede’s uncompromising vision of Afrika for the Afrikans) it is nonetheless the vision of the Azanian political tradition of Sobukwe and Biko. With the formation of the MK party, we can also agree with Mashinini that indeed the ANC is defunct. Factionalism has rendered both the PAC and the ANC dead-ends as far as the pursuit of Black Power in conquered Azania is concerned. Mashinini realised this in the 1970s and together with Seatlholo pursued the objective of forming a revolutionary alternative to both the defunct ANC and dead PAC. They formed SAYRCO. This was in order to keep alive the political objective of ending white settler colonialism and white supremacy to liberate conquered Azania. While there are those who defend the value of the formation of the MK party under the banner of Radical Economic Transformation, it should be clear to those who are committed to the politics of Black Power that we need a more radical alternative to what African politics in the form of party politics is offering today. There is a need for a more revolutionary movement outside party politics which will resuscitate the vision and politics of Black Power. It is in this sense that we need to pay attention to Mashinini’s declaration that “the ANC is defunct and the PAC is dead”.

*Masilo Lepuru is a Researcher and founding director of the Institute for Kemetic and Marcus Garvey Studies (IKMGS).