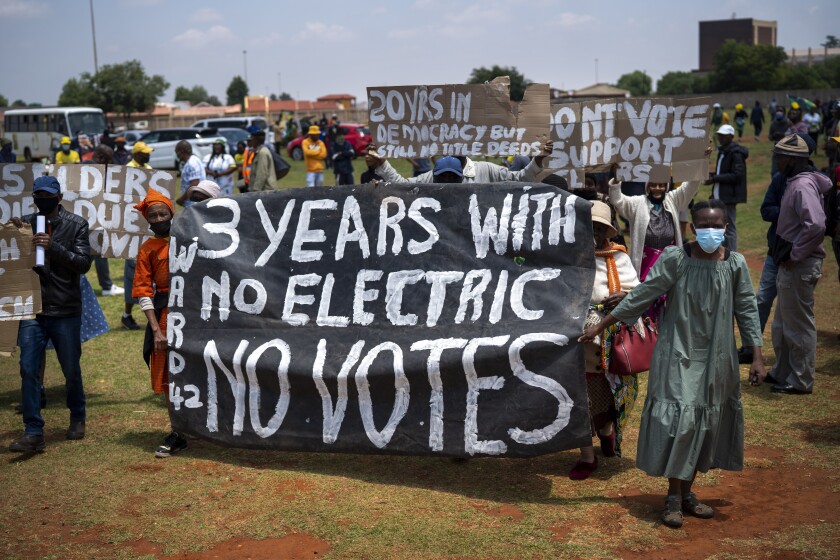

One of the biggest talking points out of the 2021 Local Government Elections, besides coalition possibilities, has been concerning the low voter turnout. In a country with up to 40 million eligible voters, only 12 million people showed up at the 2021 polls. Although voter turnout is traditionally low for local elections, at this stage this trend is jeopardising the legitimacy of our democracy and South Africa’s political stability. And the big question is whether this seemingly growing voter apathy is reversible?

Now that the period of campaign promises is over and our current politicians will inevitably go back to poor service delivery and low performance, will South Africa’s electoral process survive the next elections? To be fair, voter turnout in the National and Provincial Elections is always higher even if voter turnout was low in the previous local elections. For example, in the 2016 Local Elections voter turnout stood at 57.94% (15 million) whereas it grew in the subsequent 2019 National and Provincial Elections at 66% (17 million).

So even though voter turnout currently stands at 48% (12 million) for the recent 2021 Local Elections, it is expected that more people will come out for the next 2024 National and Provincial Elections, but still on a continued decline. A reasonable projection would be anything between 50% - 59% voter turnout for the 2024 elections, down from 66% (2019). It is hard to tell what happens after this. What is the future of South Africa’s electoral system, especially when only a minority of the voting population participates in the process?

Surprisingly, this minority of voters cuts across gender, class and race, but is found within the same age demographic. Born-frees are notorious for not voting even after being told ‘if you don’t vote, you can’t complain’. And Ama2000 are worse by not even registering to vote at all. It is unclear if these two post-apartheid generations actually know what they want. What is clear though, is that every election season they make jokes on social media about how the only way to stop a failing liberation party is to hide the ID books of their parents and grandparents on election day.

A take home lesson from the 2021 Local Elections is that although a majority of eligible voters, Born-frees and Ama2000, might be dissatisfied with the performance of the governing party, the ANC, they rather opt-out of the electoral process, than vote for one of the available alternatives. What is concerning, however, is in the misguided interpretation of the failure of the ANC to mean the failure of democracy itself, entirely as a whole. As more and more people lose trust in politicians and political parties, it seems to translate to a low trust in the democratic process - the July unrest seems to be an apt example of this.

With all these things considered, what would make the majority of eligible voters, who number 28 million, to come out and vote next time around? Half of these people (14m) have not registered to vote at all, while the other half (14m) are registered, but failed to show up on election day - maybe the matter was not that important/convincing/inspiring to follow through up to the ballot box. And still, we cannot tell how many of the 12 million people who voted this time around will go back again in 2024.

It is, of course, unlikely that any election gets a 100% voter turnout. Citizens are allowed to do or not do whatever they want, as long as that action is not infringing on the rights of another or incites harm. So, if citizens decide not to vote, it is their Constitutional right. However, if I was a practicing politician with a startup political party, I would take advantage of these recent events and the new type of politics they are signaling.

I highly doubt that the many millions of people who did not vote were rejecting democracy, political parties as vehicles for change, or the electoral system as a whole by staying home on election day, even though it was a public holiday.

In my opinion, voter apathy may be attributed to a disdain citizens seem to have in anything politicians have to say. To be a politician in democratic South Africa is to be a notorious pickpocketer who uses fine speeches to inflame people regarding their poor conditions with no intention to resolve the matter after the vote has been handed over. Will we have different politicians in the upcoming 2024 National and Provincial Elections as well as the subsequent 2026 Local Government Elections?

It seems winning public trust ought to be the number one priority of any political contender who wishes to get people to go out and vote in the next elections and the ones after. But how will South Africans ever trust any politician, ever again, especially when we have been emotionally stirred up, fired up, and let down, so many times, by unfulfilled promises of renewal? Is it even possible to rebuild trust in this day and age?

What I do know is that anyone who wants my vote next time around will have to work hard for it long before election day. As a South African who lives in the realm of political disappointments, I need to see some credible results of successfully implemented sustainable service delivery solutions, before I vote for anyone. My trust in the political system, as a South African, is low, but because I love South Africa, it can be won over. I am a convincible reluctant voter.

END