"My father had complete confidence in the intellectual and administrative superiority of the White man. He was convinced that, come what will, these would see him safely through all trouble. It would also enable him to live indefinitely in a state of semi-overlord over the Blacks. He considered this mental superiority the White man’s greatest asset." (J. C. Smuts, 1952).

A summary history of African political thought in conquered Azania reveals two dominant traditions regarding white settler colonialism and white supremacy. The first group of Africans who encountered conquest since 1652 understood the nature of the struggle as the “reconquest of the land and sovereignty” over African territory and existence. The second group, emerging mainly in the Cape colony since at least 1853, comprised victims of intellectual warfare through the imposition of European conquest’s institutional frameworks, such as liberal democracy. They saw the struggle as reducible to the “right to vote” as so-called civilized natives. This is not to suggest a chronological nature of the two main traditions of African political thought.

By the time of the founding of “South Africa” as an exclusively white man’s land by the likes of Jan Smuts, these two traditions were in constant contestation. This contestation reached its apex in 1959 and the late 1990s between the Pan-Africanist Congress and the African National Congress or the Azanian school and the Charterist school. The PAC, grounded in African nationalism and the Programme of Action of 1949, embodied the tradition of “the reconquest of the land and sovereignty,” while the ANC, based on liberal nonracial nationalism and the Freedom Charter of 1955, represented the tradition of the “right to vote”/“one man, one vote.” Many of the founding members of the ANC, as liberal blacks, accepted the legitimacy of a white settler colony called “South Africa” but complained about their exclusion, especially the lack of the right to vote. In this sense, the ANC never questioned the fundamental structure and institutions of white settler colonialism but wanted to be included. They accepted “South Africa” but lamented the absence within it of democratic rights for the African majority. Some of its famous leaders, such as Nelson Mandela, openly admired the Westminster system of the British Empire, thus the European conquerors.

The ANC embodies the tradition of African political thought that fought for extending white settler democratic rights to Indigenous people. The main problem for the ANC was reconciling “South Africa” as a white settler colony with liberal democratic rights for everyone, regardless of race. Once the ANC is located within this tradition of African political thought, it becomes easy to categorize it as a Civil Rights movement rather than a national liberation movement like the PAC. Since the violent imposition of liberal democracy in 1853 by white settlers in the Cape colony, the numerical majority of Africans has always been one of the sources of “black danger/peril” and swaart gevaar. Of course, the racial and numerical supremacy of the African majority was always a problem during the wars of reconquest, as embodied by the African political thought that foregrounds “reconquest and sovereignty.” But from 1853, it became the fundamental problem within the institutional framework of white settler colonialism. White settlers in the two British colonies of the Cape and Natal fretted about the right to vote and the fear of being overpowered by the African majority to the point of manufacturing their fake majority. Dutch settlers in their so-called Boer republics did not have to worry about the electoral power of the African majority as they excluded them per their constitutions. When the two colonies and republics consolidated in 1910 to form the Union of South Africa by the likes of Jan Smuts, both the British and Dutch settlers were concerned with the electoral power of the African majority.

To reinforce “the right of conquest,” these white settlers suppressed the African majority's right to vote through their constitutions from 1909 to 1983. Following the white supremacist philosophy of Smuts, in the sense of “the intellectual and administrative superiority of the White man,” these white settlers, both British and Dutch, faked their numerical majority through a “white democracy.” In this sense, the superiority of the White man was attained through cowardice and cheating, typical of whites as the “pale fox.” This fake superiority of the White man was reinforced by liberal white settlers who ensured that the unsustainable regime of Apartheid was replaced in 1994 with a liberal democratic regime, as had been the case since the Cape in 1853. These “friends of the natives” were assisted by their “civilized natives” within the ANC in the process of constitution-making from 1993 to 1996. The White man and woman demonstrated their “intellectual and administrative superiority” by rigging the entire liberal democratic regime again in 1996 through tricks such as the creation of the constitutional court and the principles of constitutional supremacy and judicial review.

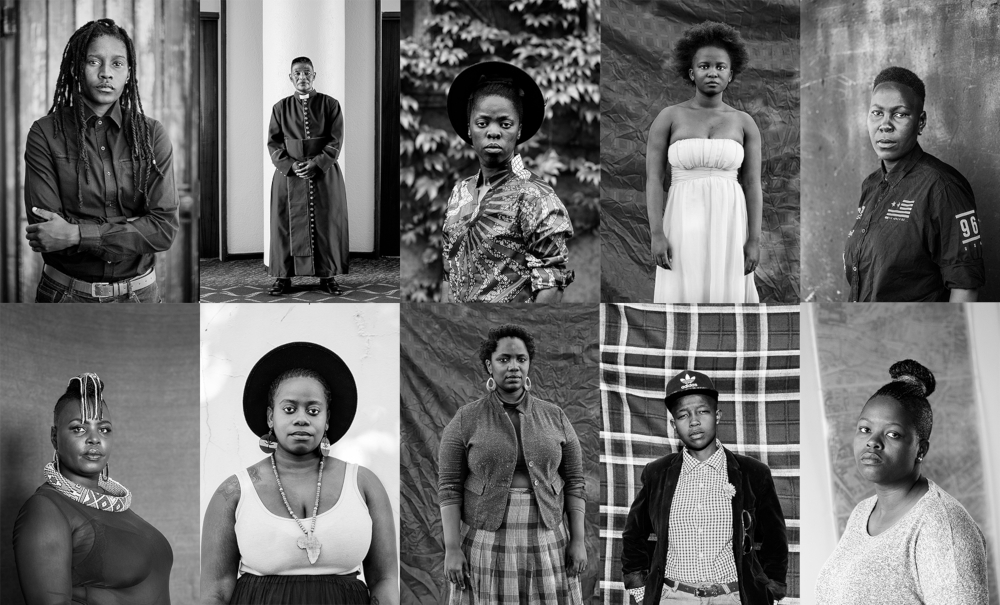

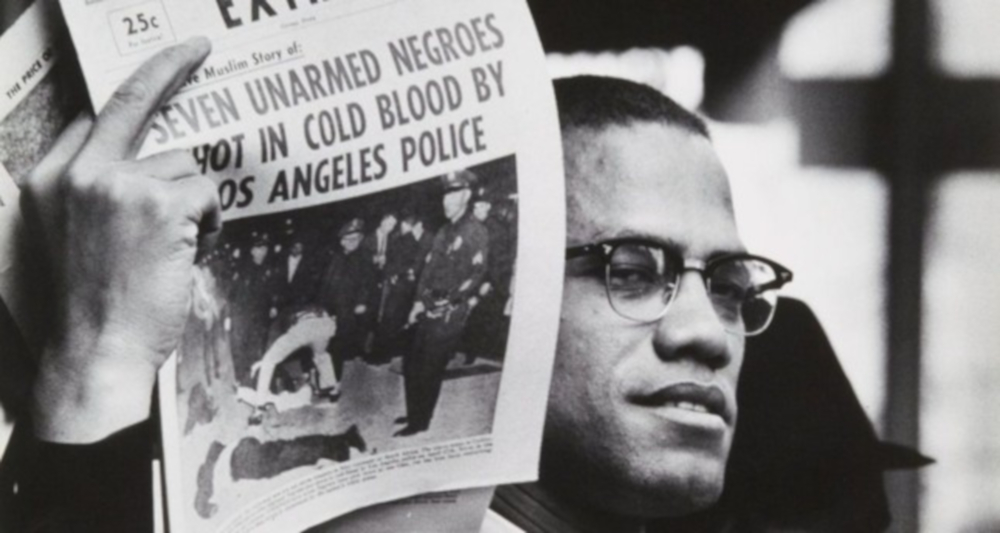

The cowardice and cheating of white settlers, facilitated by “civilized natives” of the ANC, have enabled them to “live in a state of semi-overlord over the Blacks,” as Smuts stated. In this sense, the useless tradition of African political thought, represented by the traitorous “civilized natives” in the ANC and the annoying naivety and generosity of Africans in general, has made the racist arrogance of white settlers like Smuts a self-fulfilling prophecy. Based on this brief context, we can comprehend the formation of the so-called government of national unity between the DA of cowardly and cheating white settlers and the ANC of disloyal “civilized natives” and naively generous Africans. What the naïve and generous Africans, who through electoral politics facilitated the ascendency of white settlers via the DA, fail to understand is that the problem is not the rigging of elections, but the fact that the entire system of liberal democracy, violently imposed by white settlers since 1853, has always been rigged against them and in favor of white settlers. The past thirty years of the so-called constitutional democracy have proven that the tradition of African political thought, which foregrounds the “right to vote”/“one man, one vote,” is useless. The naïve and generous African majority must abandon their fascination with the “right to vote”/electoral politics and embrace the tradition of African political thought which pursues “the reconquest of the land and sovereignty” outside the current rigged liberal constitutional democratic framework. In this sense, the African majority must reconsider their choice between what Malcolm X called “the ballot or the bullet,” thus electoral politics or revolution. “The right to vote” cannot negate “the right of conquest”; only a chimurenga/war of liberation can bring an end to whites and white settler colonialism in this order.

*Masilo Lepuru is a researcher and founding director of the Institute for Kemetic and Marcus Garvey Studies (IKMGS).