Introduction

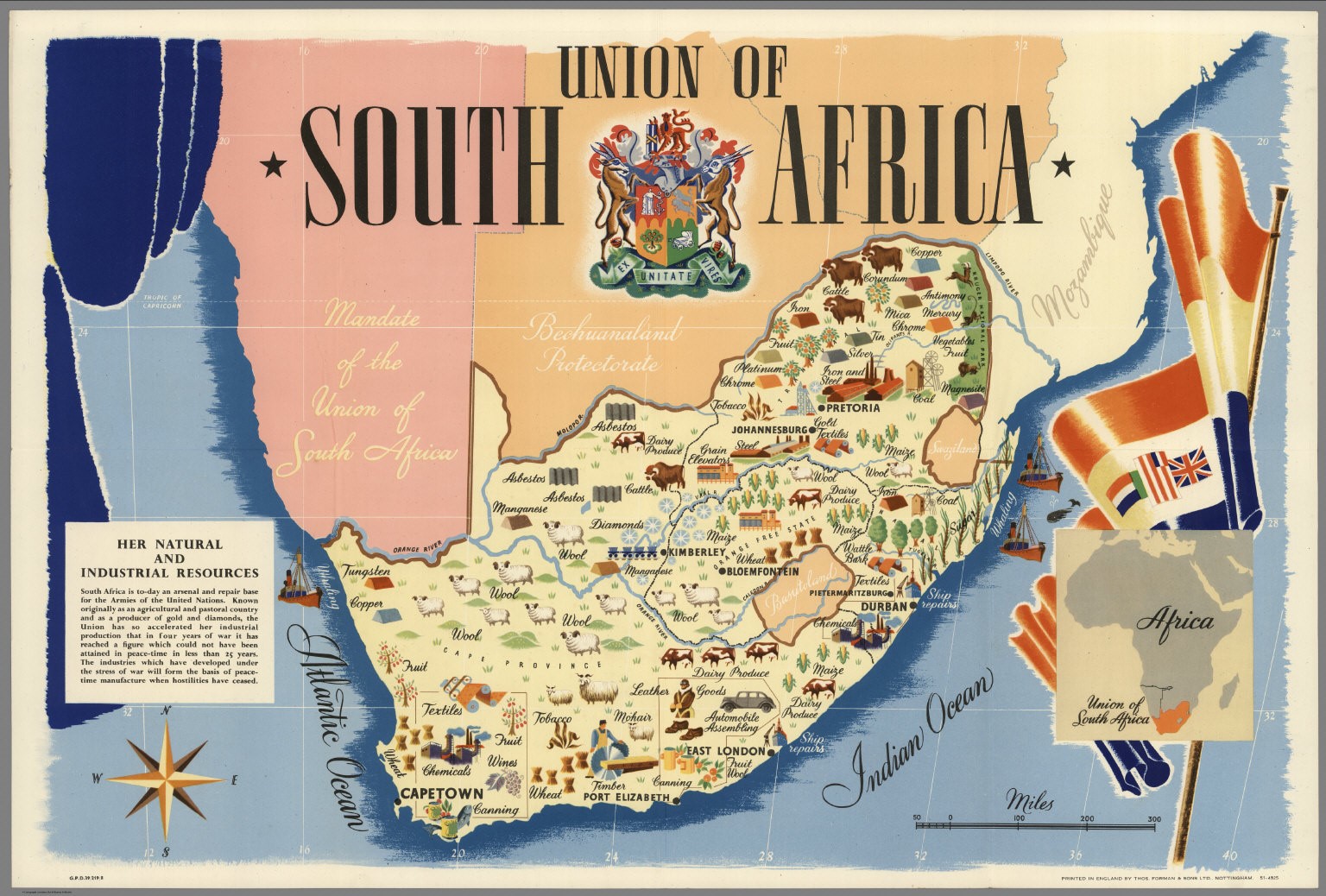

For starters ‘South Africa’s history, precedes the fifteenth century. Details of the latter will be herein omitted because their superfluous for this paper’s core interest, of founding incidents that led to origins of ‘South Africa’. Conflicts birthed ‘South Africa’, dating back (as paraphrased from South Africa’s then deputy President Thabo Mbeki’s ode, to his predecessor) to the “first moment of black anti-colonial struggle” (Johnson, 2009:123) in the Battle of Salt River on 1st March 1510 . That was four centuries before the proclamation of the ‘Union of South Africa’, on 31st May 1910.This date of 1510 indicates how cumbersome, historical conflicts among races namely between ‘blacks ’ and ‘whites’ have been, prior existence of ‘a Eurocentric’, ‘a social construct’ or a ‘postcolony ’ called ‘South Africa’. In sum after the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging in 1902, the name of ‘South Africa’ was enacted in 1910, after the British won the 2nd Anglo-Boer War (renamed ‘South African War’ ), which spanned from 1899-1902. That war unified the four colonies of ‘Cape of Good Hope’, ‘Natal’, ‘Transvaal’ and ‘Orange River Colony’.

Observably “the Union of 1910 constituted a union of the ‘white races’ and a strengthening of their position in relation to blacks” (Kallaway, 1997:430). Peter Kallaway’s aforesaid observation, is quite telling because it aptly captures, the core rationale of the delusional racial superiority, harbored by impenitent colonisers. If this was somehow vague in the late 15th Century, it certainly became much more pronounced, at the commencement of the 17th Century. Racial malice from the latter period, may explain deceptive references, when identifying colonial victims, such as “Hottentots [Khoikhoi]… Bushmen…Bantu or those generally referred to as Kafirs” (Botha, 1938:8-9). In addition ‘whites’, ‘blacks’ and ‘coloureds’ also make up, the latter derogatory list. At least in today’s democratic South Africa, “people have called for the state to recognize ancestral and cultural definition of identity and move away from ‘race’ and colour identity constructs” (Mellet,2020:309).

To be clear chronologically colonial footprints in South Africa, commenced when the Portuguese landed, in the present shores of the Provinces of Western Cape in 1485 , 1488 and Natal in 1497 while enroute towards the East, for trade which mostly included spices and medicinal herbs. Despite the latter details, Portugal’s gory colonial footprints, since the 15th Century in South Africa, are mostly unheeded . Such selective amnesia, flirts with being ahistorical. The opposite is the case, apropos the aghast colonial roles of the British / Anglo Empire and the Dutch , from the late 15th Century. This is probably because they became settlers, unlike the Portuguese “who made no attempt to form a settlement” (Botha, 1938:4). Details of arrival of the latter two, are vital.

The initial three British voyages who learnt about the Cape, sailed passed it until 1607, when Captain John Jourdain of the English East India Company (founded in December 1600) reported to his Directors on the capabilities of the Cape” (Botha, 1938:7). The latter’s reports, were somehow ignored. Once more in “1620 Andrew Shillinge and Humphrey Fitzherbert made an attempt by proclaiming the sovereignty of King James I over the country and hoisted the flag of…King James’ Mount…but the Englishmen’s action was not confirmed by their king”(Botha, 1938:5). All changed, once the “British became increasingly aware of the military significance of the Cape and the threat it could pose were it to fall into enemy hands” (Heyde, 2013:326). The Battle of Muizenberg thus ensued, from the 7th to the 9th of August 1795. On 16th of September 1795, the British victory culminated in annexure of the Cape, under King George III (ruled from 1760-1820).

The initial three British voyages who learnt about the Cape, sailed passed it until 1607, when Captain John Jourdain of the English East India Company (founded in December 1600) reported to his Directors on the capabilities of the Cape” (Botha, 1938:7). The latter’s reports, were somehow ignored. Once more in “1620 Andrew Shillinge and Humphrey Fitzherbert made an attempt by proclaiming the sovereignty of King James I over the country and hoisted the flag of…King James’ Mount…but the Englishmen’s action was not confirmed by their king”(Botha, 1938:5). All changed, once the “British became increasingly aware of the military significance of the Cape and the threat it could pose were it to fall into enemy hands” (Heyde, 2013:326). The Battle of Muizenberg thus ensued, from the 7th to the 9th of August 1795. On 16th of September 1795, the British victory culminated in annexure of the Cape, under King George III (ruled from 1760-1820).

Genesis of the Dutch’s knowledge of the Cape, is owed to the Portuguese. “Dutchman Jan Huyghen van Linschoten had sailed to India in the service of the Portuguese and returned to Lisbon in 1592…From him the Dutch obtained much information concerning the sailing directions followed by the Portuguese” (Botha, 1938:4). Linschoten’s information “served as a guide, for the first Dutch fleet under Cornelis Houtman to sail to the East in 1595 and open the eastern highway to [the Dutch] nation” (Botha, 1938:4). Similar to the British in 1600, the few small vessels of the Dutch, made way for “the Dutch East India Company [founded] in 1602” (Botha, 1938:5) which secured “the right of trading from the Cape of Good Hope eastward” (Botha, 1938:6). That’s how the Dutch, joined “the race for territorial possession and the spices and riches of the East” (Botha, 1938:6). Amid silly reasons given include, “the Cape was still waiting for a master” (Botha, 1938:6).

Initially the Dutch’s arrival in the Cape, was not promising. “In 1647 the Dutch East Indiaman Haarlem was wrecked in Table Bay and the crew…grew vegetables from seed saved from the ship” (Botha 1938:7). After the latter were rescued and returned to Holland a year later, “Leendert Janssen of the Haarlem reported to the Company on the Cape and the possibilities of forming a settlement there. The document was signed by him and a confrere, Nicolaas Proot” (Botha 1938:7). Shortly thereafter “In 1650 the Dutch Directors decided to form a settlement at the Cape. In April 1652, three ships, the Goede Hoop, the Dromedaris and the Reiger, dropped anchor in Table Bay, carrying on board the first men who were to form the settlement, under the command of Jan van Riebeeck” (Botha,1938:7). As “a surgeon in the Company’s service. Van Riebeeck immediately began to carry out the instructions of his superiors by erecting a small fort and laying out a garden in which to grow fruit and vegetables. It was imperative that the passing ships should have a good supply… for the scurvey-stricken crew” (Botha, 1938:7). Notably “meat could be obtained from the natives by barter” (Botha, 1938:7). Notably for Jan Van Riebeeck, ‘natives’ was his reference to, ‘Hottentots’ / ‘Khoikhoi’, ‘Bushmen’ and ‘Bantu’.

In closure this paper tersely narrates how “the banner of European civilization was originally planted on the Southern part of the great continent…Africa” (Botha, 1938:7) birthing South Africa, since the Battle of Salt River in 1510. So relations between colonisers and ‘natives’, may have begun by barter however they sourly evolved, to continuous mêlées, that have spanned from 1910 to date.

1 Portugal’s “Viceroy of India [Dom Francisco] d’Almeida and several of his men were killed in 1510 by Hottentots at the watering place of Saldanha, so called by Antonio da Saldanha in 1503” (Botha,1938:3). A century later Saldanha was renamed ‘Table Bay’, by Dutch explorer Joris van Spilbergen in 1601.

2 All such racial references to any group of people, must be read as part of problematic ‘colloquial speak’.

3 ...“reality with which we have been concerned all along exists only as a set of sequences and connections that extend themselves only to dissolve…ultimately a meaningless name” (Mbembe, 2015:242).

4 On 20th September 1909, a royal assent was signed by King Edward VII as South Africa Act of 1909.

5 This name corrects the myth of a ‘White Man’s War’, as among other races ‘blacks’ also participated.

6 Graham Botha (1938:1) says “one of John’s captains reached Cape Cross”. Refers to King John the II.

7 King John II’s other captain Bartholomew Diaz, coined “Tormentoso, or Stormy Cape” (Botha, 1938:2).

8 “It was Vasco da Gama who found his way to India…passing along the coast of Natal, a name he gave in memory of the 25th December, when Christian men first saw it” (Botha,1938:2).

9 The same amnesia applies to arrivals of enslaved Indians and Chinese in 1654, French Huguenots/Protestants in1688, Scots from 1772, Irish from 1795, Jews from 1820 and Greeks from 1850.

10 Eversince the rule of Queen Elizabeth I. This is why its colonies, were labelled as ‘Crown Dependencies’.

11 “Germans of sea coast, Netherlands & Flanders…people of Holland” (Fowler and Fowler, 1974:381).

12 Under Elizabethan Captains of Sir Francis Drake in 1579, Sir Thomas Cavendish in 1588 and Sir James Lancaster VI in 1591. The latter’s crew “was the first to set foot… in Table Bay” (Botha, 1938:4).

13 Succeeded Queen Elizabeth I and he ruled from 1603 until 1625.

14 Once “conscious that the French supporting Dutch in the Cape could very well refuse to supply British ships…The Battle of Muizenberg occurred when the Secretary of war in Britain was eventually persuaded to send a fleet of nine ships to the Cape to defend British interests” (Heyde,2013:326).

15 Structurally elected from one of the two chambers, Amsterdam or Middleburg. “The supreme government of the Dutch East Indies was vested in the Governor-General and Council in Batavia” (Botha, 1938:6).

15 Structurally elected from one of the two chambers, Amsterdam or Middleburg. “The supreme government of the Dutch East Indies was vested in the Governor-General and Council in Batavia” (Botha, 1938:6).

16 Structurally elected from one of the two chambers, Amsterdam or Middleburg. “The supreme government of the Dutch East Indies was vested in the Governor-General and Council in Batavia” (Botha, 1938:6).