Musa Nxumalo’s exhibition, titled We Are Running Out Of Hashtags! is an intimate photographic consideration of the limits of hashtags as symbolic grammar for organizing our experience of being in the contemporary. Nxumalo calls us to an aesthetic meditation on the #Hashtag, beyond its function as a kind of digital flag; but as an organizing force that gathers bodies around particular politics of protests or other less urgent agendas. #Hashtags, like nationalist flags, are acquisitive in the way they are able to turn followers into advocates or lobbyists. In this way, we may say that it is #Hashtags that have people and not people who have #Hashtags; like flags are for nation–states and citizens.

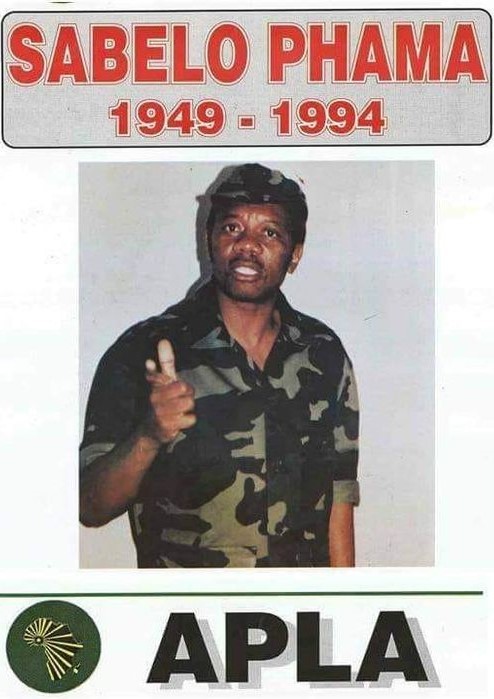

Indian writer, Arundhati Roys holds an instructive cynical view of flags as bits of coloured cloth first used to shrink-wrap people’s minds; then as ceremonial shrouds to bury the dead. Our age has no shortage of deaths, or #Hashtags to memorialize them: #JusticeForTshego; #BlackLivesMatter; #JusticeForShoni… But, beyond the tweeted outrage with its accompanying images, can they hold without running out? Nxumalo’s new work tries to trace out possibilities of the photographic image deployed as a kind of flag.

In his series, Story of O.J., after 4:44, Nxumalo presents a selection of portraits of young black men standing semi–nude with only their pants on, an occasional hat, but no shirts. They pose for Nxumalo’s camera in the tradition of tattooed gang members being studied by law enforcement lenses trained on their torsos for toll-tales of lived criminality. Only there are no inked marks on Nxumalo’s displayed bodies. Only refracted light, the apparent softness of maturing flesh, and the embodied black boyhood as it fades into manhood.

The pictures are printed and hung like flags as opposed to being framed. The back of these flags are completely black. Nxumalos’ semi-naked subject is coded; not unlike a media hash-tag. In popular discourse, the black male body exists and appears always tagged with myriad culpabilities for immeasurable deviences; both real and imagined, earned and projected.

However, Nxumalo zooms in on this discursive limitation by zooming his lens in on their vulnerability, eschewing urban machismo mythologies with an intimate photographic gaze.

These mythologies govern how we identify, classify and often fail to see the vulnerability of urban black males. In the poem, Twenty-six Ways of Looking at a Blackman, Raymond Patterson hints at this idea of the invisibility of blackman’s vulnerability. The ninth stanza, or way of looking, declares the following: Children who loved him // Hid him from the world // By pretending he was a blackman. Patterson points us to a pretended black manhood, as a hiding place, a performance of public invisibility. Nxumalo’s lens is asking us to look and find it beyond the shallow reach of #hashtags.

Beyond these probing portraits, the show includes a wall, designed street-poster style, with pasted images to announce the title of the exhibition. The visual grammar of the street poster, coalesces with the picture flag and syntax of #hashtags to underscore Nxumalo’s focus. There’s a public life of ideas and a spectacle within which the meaning of our shared lives is occasioned. The limits and excesses of that spectacle underscores Nxumalos work.

The exhibition also includes projected selections from Nxumalo’s previous bodies of work: Anthology of Youth (2016), 16 Shots (2017). Alternative-Kidz and others, registering continuity in Nxumalo’s practice. These echoes of earlier work give context to his new interest in pushing the limits and possibilities for presenting the photographic image. The projection, the hoisted flag, and the wall of pasted posters are part of this growing creative concern.