Question: Is there any link between actors who improvise well, and actors that write?

I assume that there is. This assumption is based on the fact that as an actor, one has to – in the moment – have the ability to go off-script by necessity of circumstance. In this off-script moment, whether in rehearsal or performance, the actor must ensure that the adage that, “the show must go on” is lived up to. Her job becomes reattaching a thing that has broken off from itself, a feat that requires a depth of understanding which transforms the hesitation wrought by the imbalance of breakage into cool, calm and collected control (of story, audience and performance).

The actor takes on a sage-like essence, by being so attuned to the moment that the breakage is soothed and manoeuvred into an unforeseen bend on a road that was otherwise without obstacle. This actor guides the enrapt audience further into the unfolding world, which presents itself to them for the first time. For audience and characters alike, there are no mistakes – unless the actors give way to the interruptions. Like the audience, the characters do not know that the actor has forgotten their lines, and it is taken a level deeper when one considers that, although the audience is aware of the character-actor duality, the characters are not aware of their status as characters, or that of the audience likewise. Thus, every time a performance unfolds, the actor must be aware that, for the audience and the characters, everything is happening anew. Furthermore, for the characters, the script does not exist, therefore when an unplanned occurrence happens upon the character’s reality, the actor must improvise.

The rupture, unaccounted for in the script, creates a volatile chasm that could potentially swallow up or rip apart the hard-won suspension of disbelief that has resulted in the communion of an agreed illusion. The actor knows that this situation cannot be allowed to persist. She knows that, while it is true that some things can be so damaging as to cause the performance to be unsalvageable (say a bombing, or a madman bursting in with an assault rifle and intent to kill), there are those moments when something significant enough to break the rhythmic flow of the performance happens, and the show can only continue if the actors improvise.

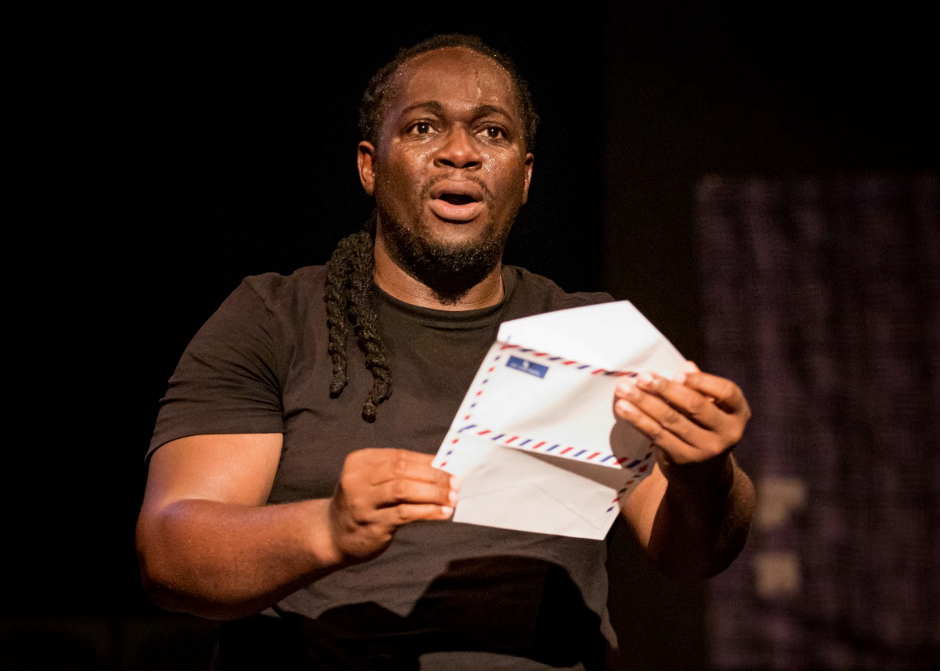

I recall here a personal experience from 2018, when there was load-shedding during a performance of Sibusiso Khwinana’s Best Friends Worst Enemies at the National Arts Festival. As actors, we were taken aback by the sudden darkness, and in an almost magical moment, all of us on stage reacted as if the lights had gone out in the house we were (performing) in. Almost as a way of improvising and rewriting the story with us, the audience turned into a lighting crew, as they whipped out their phones and switched on their torches – to help an independent ensemble reach the end of the last ever run of this production.

As smart as Khwinana was in his writing, there was no way he could have foreseen such an occurrence. Though the load shedding experience may be unique to my own journey as an actor, most actors probably have similar stories – where something caused the show to be interrupted, and improv provided a way back into the story – and I’d be willing to even assume that many of these instances would have required actors to get the story back on track without the audience’s assistance.

In such moments, where improvisation is necessary to salvage the world of a story, the actor – and this is my claim – taps into the same creative resource that the writer draws from, albeit under differing circumstances. The writer does not deal with the same set of demands that face the actor in performance, however… both are invested in the ultimate success of the creation, this otherwise non- existent reality. In developing this world, the writer had to immerse herself in the elements that would lead to the construction of as satisfactory a world as possible. The process of rehearsal breathes life into this world, and the performance is a manifestation of the world as it exists in motion – and for this final phase to be successful (in the context of creative intention) it requires the actors to bring to the fore all those factors discovered during the rehearsal process. Thus, when a fracture occurs, the gap presents a challenge that can only be dealt with by the actor – for the writer cannot be immediately summoned to add a few lines to make the accident make sense.

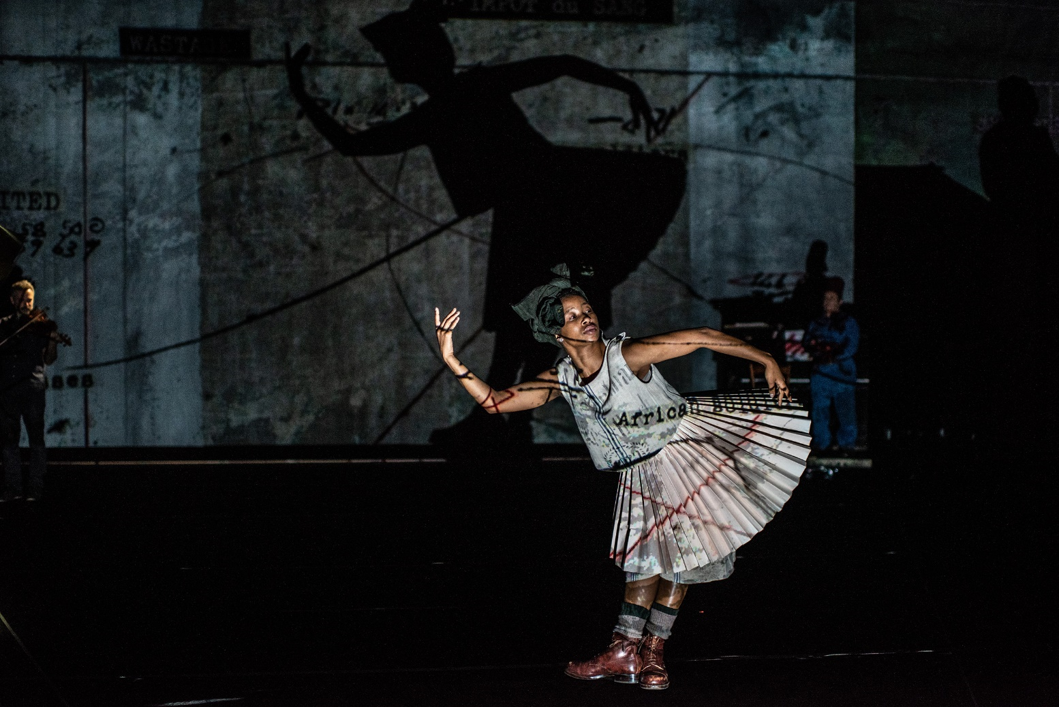

It is in this space that the improvising actor turns into a momentary writer, as she takes action to bring the story back on course. She redirects the narrative through word and action, with the sole intention of returning to the world created by the writer, and developed through the rehearsal process. She makes the break-in-the-chain make sense. She writes, in the sense that everything that happens on stage is presumed to be a projection of what has been scripted. In that (allow me this liberty) sacred moment, the improvising or writing actor takes on the responsibility of lifting the fallen spirits of those around her (even those responsible for the rupture). She gracefully allows for correction to take place without pain. This suggests to me that actors who improvise well may have a latent writing ability. If we are not rigid in our conceptions of writing, and look upon the craft as clear-intentioned storytelling, we can see how the body can “write” a story – as it weaves and blends together images, movements and words. These embodied images can become cues for sparking memory, and lead to story matter being pulled out from the ether, so as to be used to reconnect a tethered narrative.