From the beginnings of modern formats of theatre making in South Africa, alternatives to the recognized, mainstream modes of creation have always existed. One need not think far to see how protest theatre in South Africa was carried by alternative performance spaces that were modelled into theatres by the necessity for a public engagement on the issues of the day. With no access to the segregated state subsidized stages, theatre makers with a desire to speak truth to power from the stage had to turn to halls, shebeens, churches and community centres. Thus, creating an independent alternative to what the national purse strings regarded as legitimate.

Coming off the back of The Writers Lab’s inaugural Reading Festival, we wanted to remind ourselves of what it means to make theatre outside of the “mainstream” today. At a colloquium hosted earlier this year by The Writers Lab at the Tshwane University of Technology’s Drama Department, Mpho J Molepo asked a pertinent question about the definition of the title Independent Theatre Maker as it has seen a resurgence in recent times, pioneered by young artists throughout the country. What was it about this wave of theatre makers that was so distinct from previous movements emerging in the past? Today, prominent young theatre makers that have identified themselves under the moniker include practitioners from the Eastern and Western Capes, KwaZulu Natal, Gauteng, the North West and several other regions throughout the country. Those mentioned above seem to have maintained greater visibility in the wider theatre world, but are not the only ones by any stretch of the imagination.

So, what defines and unites these disparate voices? Is it a lack of resources and access to funding? Is it a result of marginalization from the state funded institutions? Is it the characteristic of angry disorganization and incoherence? Or could it be a solid desire to attain the desires of a particular type of consciousness that has (re)emerged in the charge to overcome the stifling questions posed above? When one looks at the art of making your own work by any means necessary, whether you have resources, funding, a venue, a budget or not, while retaining the creative control of the work in question, one starts to understand what it means today to be an independent theatre maker.

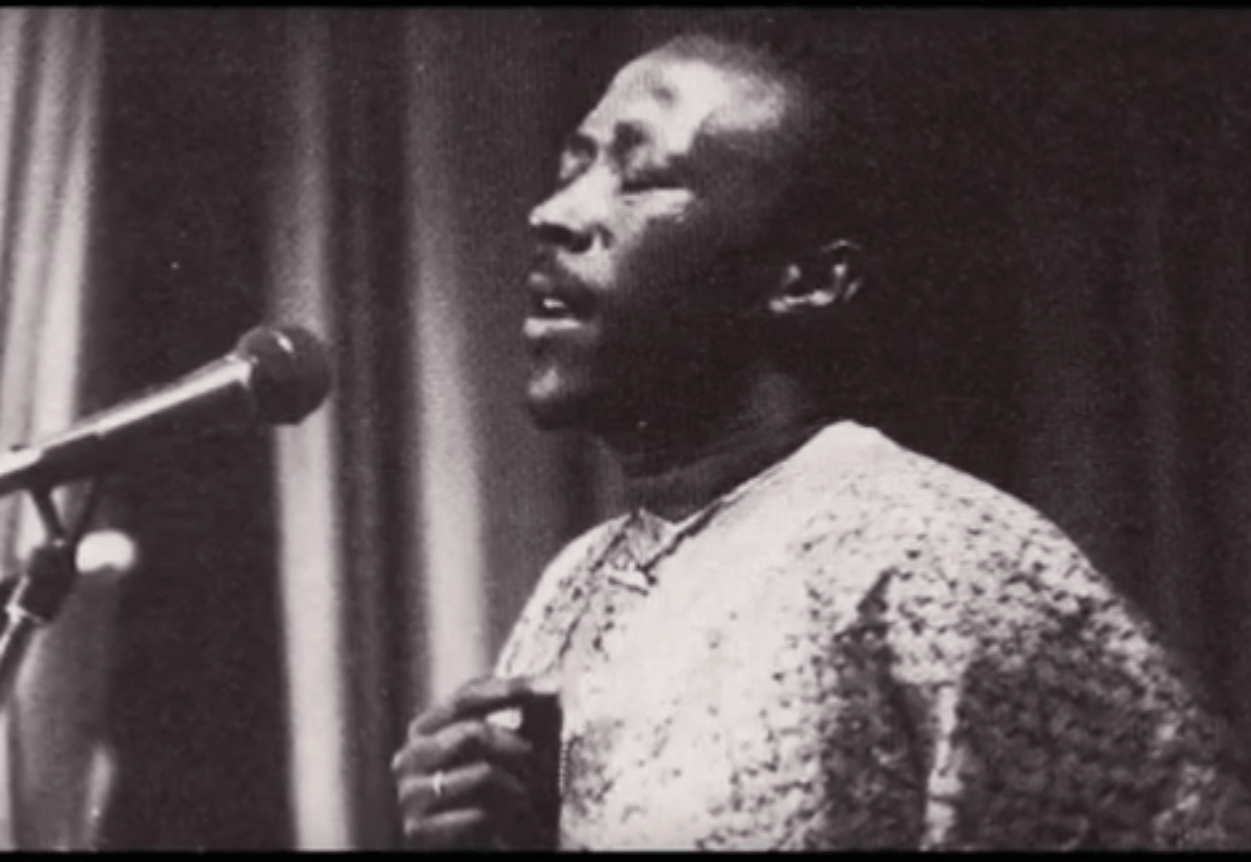

Few others have understood or lived this reality to the extent of one of the sharpest creatives to emerge from the city of Tshwane. A young, bright, lanky, nappy haired genius with a calm demeanour and an authoritative ease of rapport, the brilliant, Sibusiso Khwinana. To those unfamiliar with the legacy he leaves behind allow me to (re)introduce you to a late giant of the theatre. Affectionately known to many as “Sobi Dikuku” or “Sbu/Sbuda/Sbuda-Man,” this Sosha-based firebrand made a name for himself in various ways in a relatively short period of time. Entering the theatre scene through Youth in Trust, an institution based at the South African State Theatre, Sbu was clear about what he wanted to achieve. A passion for Orlando Pirates gradually surrendered to a love for the alchemy of the stage. He staged a number of shows during his time at the State Theatre, and continued to do so upon his exit.

Once he had finished his training, Sbu made it his mission to make and consume as much theatre as humanly possible, but the problem of access to a space posed a great challenge to the former, and in a roundabout way to the latter. In his solutionist nature, he unearthed a relatively infrequently used hall in what used to be Pretoria’s Bosman Fire Station, later styled, The Tshwane Arts Hub, located at 46 Minaar Street, a block away from Bosman Bus and Taxi Stations. Through innovative thinking and in partnership with a network of collaborators (at TX Theatre Productions run by Mongezi Mabunda and Mxolisi Masilela, Blankpage Entertainment run by Sbu alongside Thato Vejah Moeng, James Sithole, Lehlogonolo Xauka and Thandeka Khwinana and Black Ink Productions run by Ronald Manganye), Sbu co-led the efforts that resulted in the creation of The Station Theatre and a collective called the Independent Theatre Makers. The Station Theatre, a space that did not exist as a theatre a decade ago, has managed to host, with very limited resources, multiple annual festivals each with a number of original works created by young South African theatre makers. Prominent shows have included Tswalo by Theatre Duo, JBobs Live by Jefferson Tshabalala, The Cursed Vagina by Paul Noko and Hannah van Tonder, Boy Ntulikazi by Thobani Nzuza and Flamebook by Xolisa Ngubelanga. The Station Theatre gave a space to Tshwane based theatre makers and those from other parts of the country an opportunity to stage work that was rejected by, or on a convoluted journey to the mainstream stages. Contrary to what may be assumed, this resulted in a deeply rich offering of work that was able to grow through having a space to be developed without the constraints of stifling deadlines or creative controls that could suffocate a work that needs time to breathe. Many of these shows, as is well known, then went on the perform at mainstream festivals throughout the country, after receiving a much-needed period of gestation at The Station Theatre.

This also resulted in the growth of a network of artists that otherwise did not have access to a platform in which to consistently work at their craft. As the profile of The Station Theatre began to expand, its reach went beyond the capital city through many different initiatives of which Sbu was an integral part. These included the Independent Theatre Walk that saw a 35km trek from the Station Theatre to the TX Theatre in Thembisa, the 012-011 and 012-013 Monologue and Duologue Festivals which travelled to Johannesburg and the North West Province and the State of the Nation Address Theatre Festival which hosted shows by creatives from Johannesburg, KZN, the Eastern Cape and the North West. These exchanges continued the expression of a vision for a circuit of alternative spaces for work made by young independent theatre makers throughout the country. This is perhaps a fundamental difference to previous independent theatre movements that may have been clamped down by state intervention. The ability to widen the reach of a work or collection of works through a touring circuit of independent spaces was systematically taken away. But this is no longer the case, even though resources are still hard to come by.

In addition to work done through the Station Theatre, Sbu was also an astute, award winning theatre maker, writing and staging his own work to acclaim from audiences that consistently filled out the auditoria to see his work. One such work, Best Friends Worst Enemies won a Standard Bank Encore Ovation Award in 2018 and received controversial, yet brilliant feedback from festival reviewers, festival goers, and award panel members. Wherever the show was staged, the audience showed up, and this was nothing new for Sbu whose first and second works had similar trajectories. These were Tit for Tat and Amend. He also directed Kudela Owaziyo, Ubhuku Lwa Manqe, Reen Bloed Nasie, Don’t Start, Iyeza, The Crucible, The Essence of Coit, Brothers in Blood and Mother Courage and Her Children. In extension to being a deft director, Sbu had no qualms with working behind the scenes to build the world of a work, or run a show as a stage manager, with his credits including The Infidel by Tshepo Ratona, Road to Damascus by Bongani Masango, The President’s Man and Protest both by Mpumelelo Paul Grootboom and Angola by Sello Maseko, after which he won an award in recognition of his contributions to the theatre world at the Trade Fair hosted at the Market Theatre.

The climactic moment of Sbu’s young career, the one which we were still celebrating when our merriment turned to weeping, a bittersweet film debut that took the world by storm, became the last image on our minds of an unassuming revolutionary. Matwetwe, Kagiso Lediga’s smash kasi film, hit our shores like a typhoon, and we saw Sbu, a leading man alongside long-time friend (also a theatre maker) Tebatso “Prodykal Son” Mashishi, prove the boundlessness of his talent when what we knew him for – organizing a community around a vision for independent theatre and writing and directing amazing theatre works – was just a taste of his skill. We were all blown away by the revelation of his talent as a screen actor and took pride in seeing a film doing so well locally, as to break records, and compel theatre houses that had not picked up the movie at first to open their doors to yearning audiences. Just as he had opened the doors to the theatre sector and filled up the halls to the brim in the live medium, when he appeared on the giant screen, he had the same effect.

He left the scene when he had reached a quarter century, but he left a blueprint for those willing to continue in the cause. I do not wish to make it seem like he did any of this alone, but his leadership capacity, consistency, determination and discipline led many disillusioned souls back into the therapeutic rehearsal space. In this way, we can start to appreciate the healing quality of the consequence of meeting Sbu. Once was enough, and once you knew him, you knew what he was about: Independent Theatre Making. Some of his favourite phrases were: “We are the future!!!” “Independence is the future!” “There is no way we are not going to make it!” and the infamous “Where is the hope?”

That last phrase/question leads me to considering Sbu’s contribution to the organization now known as The Writers Lab. With a deeply inquisitive approach, Sbu was always on hand to offer constructive critique to writers in search of an authentic, yet compelling narrative. As a member of the steering committee, in addition to being involved in more projects that anyone might actually know, he also led a workshop on writing for the stage, using his favoured 3 Act Structure to take attendants through his approach to storytelling. (Best Friends Worst Enemies was perhaps his best illustration of the 3 Act Structure in process, and a follow up article could consider his aptitude as a writer.) He also directed Tebatso “Prodykal Son” Mashishi’s Reen Bloed Nasie, a controversial play that was developed through The Writers Lab. We couldn’t close off this year without an acknowledgement of his contribution to us as an organization, to the theatre sector in Tshwane, Gauteng and South Africa as a whole, and to independent theatre making as a practice and as a consciousness.

Sbu’s approach to theatre as an idea and a practice provides the definition of an independent theatre maker today. At the very least, he has provided the clearest answer to the question asked by Mpho Molepo above. So, what does it mean to be an independent theatre maker today? For me, it is to come as close as possible to the example, the guideline, the template, the blueprint, the foundation laid out by a revolutionary theatre maker, lover and soldier, Sibusiso “Sobi Dikuku” Khwinana.

Peace unto you all

On behalf of The Writers Lab and the Independent Theatre Makers

Katlego Chale

Artist – Scholar

katlegochale@gmail.com